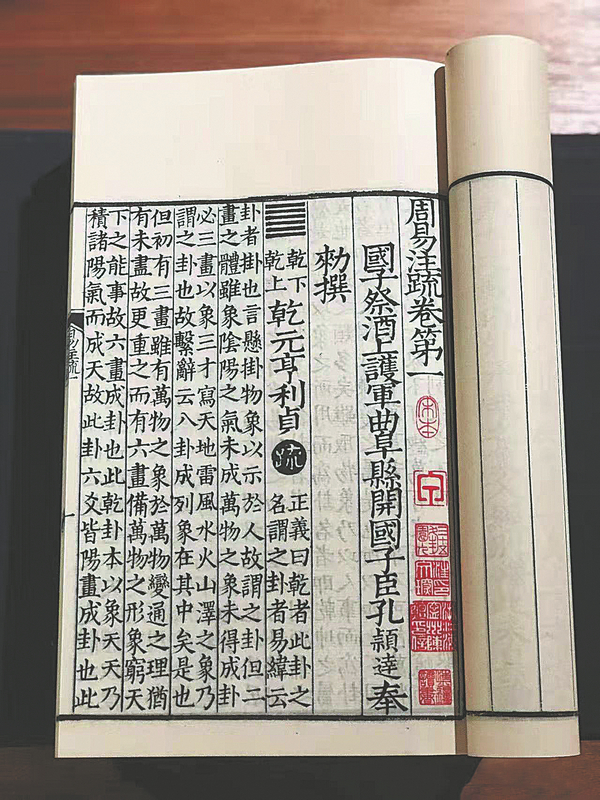

A page from history

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China Daily, January 7, 2022

E-mail China Daily, January 7, 2022

For example, for Records of Great Learning by Confucian philosopher Wang Yangming (1472-1529), the edition under the reign of Emperor Longqing (1537-72) of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), which was kept in Zhejiang Provincial Library, was initially used. Now, the edition printed under the reign of Emperor Jiajing (1522-66) of the Ming era has replaced the former edition. This edition, which is kept in the National Library of China in Beijing, is older and better in content.

The paper stock chosen also makes a huge difference to the quality of the replica books. The traditional paper, known as xuanzhi, used for traditional painting and calligraphy, is made of straw and bark and cannot be used as it is too soft and too easy for ink to spread if printed with traditional lithography technology.

There is machine-made paper for printing such books, but it leaves much to be desired in terms of quality.

So where does the paper to make the books come from? The technology for the making of such paper has long been lost.

Jiang Fangnian's interest in ancient Chinese books led him to establish a mill in Fuyang, East China's Zhejiang province, in the early 1980s, where the technology of making this kind of ancient handmade printing paper was reinvented. Known as yuanshu paper, it is the same type of stock used for the printing of ancient Chinese books. Made of fresh bamboo and tree bark, it is harder than xuanzhi, but softer than modern paper, and is perfect for the replication of ancient classics.

Jiang Fengjun, daughter of Jiang Fangnian, compared the quality of the two kinds of traditional papers. She soaked the two kinds of papers in water for a month, the paper from her mill can still be used after drying up, but the other disintegrated into pulp. She put her handmade paper in the sunlight for a month, the words printed on it remained unchanged.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)