History

A groundbreaking financial innovation in ancient China

Jiaozi (交子), which emerged in China's Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127), marks the inception of the world's first paper currency. It was not until six centuries later that Sweden issued the first paper currency in Europe, and the Bank of England, the first bank to initiate the permanent issue of banknotes in Europe and America, was an even latecomer. The introduction of jiaozi had a profound impact on the financial and economic systems of the Northern and Southern Song dynasties, as well as the Yuan (1206–1368), Ming (1368–1644), and Qing (1616–1911) dynasties of China, and even on the world's financial system.

In ancient China, where metal coins were the standard currency, why did the Song Dynasty begin to adopt lightweight and cost-effective paper as a form of currency? What led the Song people to trust that paper could function as money and be willing to have it represent their wealth?

The birth of jiaozi as currency

Jiaozi, a term in historical context, may not readily bring to mind the concept of paper money for those unfamiliar with its historical background, as its literal meaning is not associated with "钱(money)," "币(coin)," "元(sycee)," or "金(gold)." The character "交(jiao)" implies the act of handing over or exchanging, making jiaozi essentially a voucher for monetary transactions or exchanges.

The term jiaozi indicates its operational mechanism. While we categorize jiaozi as paper money, to be precise, it would be more accurate to describe jiaozi as "currency crafted from paper." It is essential to recognize that the characteristics and operational mechanisms of paper money in the Song dynasty significantly differ from those of contemporary paper money, and thus, they should not be equated.

In 1024, the Northern Song court declared the establishment of the "Yizhou Jiaozi Office" in the Chengdu region and following preparations, officially launched the state-issued paper money known as jiaozi. The advent of jiaozi predates the emergence of paper money in other regions of the world by six centuries. Bridging the Sui and Tang dynasties (581–907) with the Yuan and Ming dynasties (1206–1644), the Song dynasty was instrumental in carrying forward and innovating in numerous domains, including the economy, politics, and culture. The currency domain was no exception, with jiaozi and other paper monies epitomizing this innovation.

Why did jiaozi originate in the particular historical phase of the Northern Song Dynasty and the specific region of Sichuan? Pinpointing the complete set of reasons is challenging, but the advent of a revolutionary financial innovation is invariably driven by some particularly key factors.

Scholars have shown that compared to previous dynasties, the Song Dynasty's economy was more advanced, with substantial development and innovation in merchandise trade, marketplaces, and state finances. The evolution of commerce and fiscal systems necessitated a currency that had higher denominations and was easier to circulate, especially for long-distance, large-volume trade and accounting purposes. Yet, the primary currency in circulation during the Northern Song Dynasty was copper coins valued at a mere one wen ("文"), and in Sichuan, the situation was exacerbated by the prevalence of iron coins, which had even less value and were more cumbersome to transport and store. This inconvenience affected local authorities, merchants, and ordinary people alike. Thus, the advent of jiaozi was an imperative solution to these challenges.

Instruments like the so-called "flying money" (a kind of exchange bond) for inter-regional currency transfers in the Tang Dynasty, the cash notes introduced by the Northern Song authorities, and the tea and salt bills (government-issued vouchers for licensed merchants to collect and sell tea or salt) had been long utilized in state finance and commerce. There was, therefore, an established practice of using bills to represent currency and goods, and both officials and merchants had put together systems and experiences related to these bills. Hence, for the Song people, paper money was not an innovation that emerged with zero basis, making its acceptance relatively straightforward.

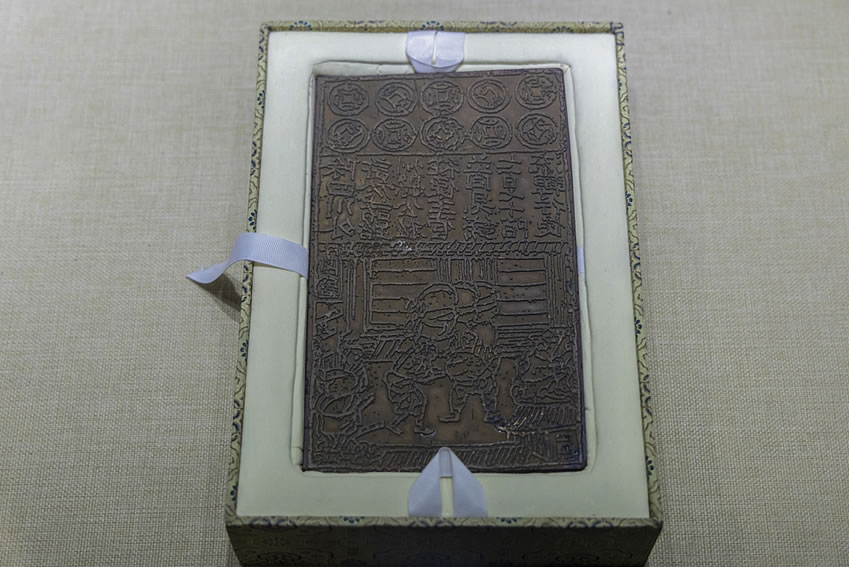

Furthermore, the specific conditions in Sichuan greatly facilitated the emergence of jiaozi. Despite having key transportation routes linking the region to its surroundings, Sichuan was relatively sealed off geographically, particularly given its distance from the Northern Song capital, Kaifeng, and it was not the most vital area for sustaining the national finances of the Northern Song. Consequently, the imperial court's economic control over Sichuan was comparatively lax. Additionally, Sichuan possessed the necessary raw materials and technological capabilities for producing jiaozi. As the hub of papermaking and printing during the Song Dynasty, Sichuan was the birthplace of the mulberry bark used for paper and was home to numerous craftsmen who had mastered the most sophisticated block printing techniques of the era, including the complex process of color printing.

The value of trust

The development of jiaozi can be divided into two stages: private and official.

The privately operated jiaozi was managed collectively by sixteen affluent merchants from Chengdu, who would hold regular meetings to discuss business strategies. After assigning certain extra social duties to the operators, local officials did not interfere in the daily operational management of the jiaozi. Holders of metal currency could deposit their money at any of the jiaozi shops to exchange for jiaozi, and they could also request cash redemption at any jiaozi shop. Jiaozi notes did not have a set denomination; instead, the amount was filled in temporarily based on the deposited sum, with all sixteen merchants recognizing jiaozi notes issued by each other.

Jiaozi alleviated the inconvenience of carrying heavy iron coins for both traders and civilians, leading to its widespread acceptance. It was utilized for pricing and payments alike. Nevertheless, the consortium of 16 affluent merchants quickly ran into difficulties, failing to meet their obligations to redeem the notes in full. Consequently, jiaozi, as a novel financial instrument, encountered a crisis of trust, and the monetary circulation in Chengdu and other areas suffered a significant disruption.

Some local officials attempted to ban the use of jiaozi, while others, who were more enterprising, believed that jiaozi was indispensable to the local economy and advocated for the rectification of privately issued jiaozi and for the government to re-open the currency. The Song court endorsed the latter view and, announced the establishment of the "Yizhou Jiaozi Office" in 1024, which was specifically responsible for the issuance of jiaozi. Thereby, jiaozi transitioned from being privately managed to being officially operated, a phase that lasted until the fall of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279).

The operational mechanism of the government-operated jiaozi was initially very similar to that of the privately operated jiaozi. The public could deposit money to obtain jiaozi and also redeem money on demand. The "Jiaozi Office" also kept a reserve of 360,000 guan of iron coins (one guan equals 1,000 wen) as capital. As the circulation of jiaozi expanded and its liquidity increased, the deposit-redeem model no longer met the needs of the government and the public for jiaozi, leading to a significant transformation in the operational mechanism of the government-operated jiaozi.

Firstly, the public was no longer required to deposit money, and the government ceased to redeem jiaozi; instead, when one issue of jiaozi expired, it was replaced by a new issue. Secondly, the denominations of jiaozi transitioned from being temporarily filled into being fixed. The initial fixed denominations were five guan and ten guan, which later stabilized at 500 wen and one guan for the long term. Consequently, jiaozi in Sichuan moved away from the redemption model and truly became a circulating currency used daily by both officials and civilians.

Outside of Sichuan, the court still promised that jiaozi could be redeemed, but this was limited to certain special channels that were crucial to national finance, such as the purchase of military supplies in Shaanxi.

Shaanxi is located at the border between the Northern Song Dynasty and the Western Xia (1038–1227), where a large number of Song troops were stationed for a long time. In addition to relying on tax collection, a large amount of military supplies such as grain and fodder were also obtained through official purchases from civilians, with Sichuan merchants being significant participants. To facilitate their settlement and transportation, the court introduced jiaozi into the procurement of military supplies in Shaanxi, announcing that jiaozi would be used to pay for the supplies provided by Sichuan merchants and could be redeemed at designated locations. Participating in the purchase of military supplies in other regions marked the departure of jiaozi from Sichuan and its move to the front stage of national finance.

A groundbreaking innovation in financial history

We say that jiaozi represents a groundbreaking innovation in the history of world monetary finance, and the reasons go far beyond its early appearance. The breakthroughs in the form of currency that jiaozi achieved, as well as the underlying institutional support and innovative mechanisms, are the historical treasures that truly deserve our attention.

The birth of jiaozi broke through the traditional limitations of using metals or other high-value physical objects as currency, marking a significant innovation in the form of money. The thin paper made from mulberry bark itself had little value and could not guarantee the value of jiaozi. Both privately and officially issued jiaozi were backed by strong supporting systems that ensured their value.

During the private issuance phase, the foundation for the issuance of jiaozi was based on the financial strength of 16 wealthy merchants and the trust people had in their financial capabilities. Trust relationships and commercial credit entered the monetary field with the issuance of jiaozi, demonstrating their potential to become the basis for monetary operations. Although the privately issued jiaozi failed due to the inability to redeem as promised, issuers had already realized that the amount of jiaozi issued did not need to correspond strictly with the amount of iron coins deposited, which is quite similar to the operation of modern credit money. However, how to grasp the coefficient between the amount issued and the capital base still requires long-term exploration.

During the official operation phase, the issuance basis of jiaozi became more complex, with the official mobilization of various financial resources and institutional tools to endorse jiaozi. A cash foundation of 360,000 guan was the basis for the issuance of jiaozi, accounting for about 30% of the total jiaozi issued. Even in the Southern Song dynasty, many officials unrealistically advocated that paper money should be backed by 100% reserves, so the designers of the official jiaozi system had been far more insightful than the general level at that time.

In addition to the capital, the value guarantee of the official jiaozi also included legal regulations and financial resources represented by the monopoly of tea and salt. In fact, the monopoly of tea and salt was not only an important channel for the Song court to obtain fiscal revenue, but also the largest, most attractive, and most influential trade activity at the time, capable of driving the exchange and circulation of related materials. The official facilitated the circulation of jiaozi in the monopoly trade of tea and salt, indirectly securing the value of jiaozi with the value and expected returns of monopolized goods such as tea and salt, as well as stable circulation channels.

By the mid-to-late Southern Song dynasty, the Song court mobilized more fiscal resources to maintain the operation of paper money, truly permeating paper money into every aspect of national finance. Therefore, it can be said that the state played a leading role in establishing connections between paper money and fiscal resources beyond currency, such as monopolized goods, which is the most distinctive innovation of the paper money system in the Song Dynasty.

Stimulating the economic and trade vitality

For many market entities, the emergence of jiaozi signified the appearance of a currency in the circulation field that could be used for accounting and settlement of medium to high-value transactions.

Taking Sichuan as an example, the face value of iron coins was one wen, and it took two iron coins to equal one copper coin, indicating that the value of a single iron coin was very low. It was common for people in the Song dynasty to carry money in carts when shopping, or to wrap strings of coins around their necks and waists. The phrase "waist wrapped with ten thousand guan" is, of course, an exaggerated way to describe someone as wealthy, but it truly reflects the way ancient people carried their money.

Besides iron coins, there were limited transactional mediums available. The people of the Song Dynasty, apart from engaging in direct barter for bulk goods, would use precious metals like silver. However, silver was not the primary currency during the Song period, and even the smallest unit was 10 liang (approximately equivalent to 20 guan of copper coins), which was a vast difference from the face value of a single wen of copper or iron currency. Jiaozi bridged the monetary gap between metal coins and precious metals, invigorating the economic and trade vitality of the Song Dynasty.

In terms of national financial system construction, the significance of jiaozi extends well beyond providing a new currency for fiscal activities. Hindered by the limitations of mineral extraction and weight, copper and iron coins could not handle the task of large-scale, long-distance allocation of fiscal resources. In contrast, the issuance of paper money like jiaozi was almost free from the constraints of raw materials and costs. The lightweight nature and higher denominations of these notes enabled the court to manage and allocate national fiscal resources more effectively through currency.

The proportion of currency in the Song Dynasty's national fiscal revenue and expenditure far exceeded that of the Tang Dynasty. The period between the Tang and Song dynasties was characterized by the transition of national finance from a goods-based system to a currency-based one, and the advent of jiaozi undoubtedly accelerated this historical transition.

The state relied more on disbursing funds to different regions instead of physical transfers, which in turn stimulated fiscal purchasing activities and exchanges between the government and merchants. Scholars argue that the extensive government purchasing activities catalyzed the flourishing of the civilian economy and the innovation of financial instruments in the Song Dynasty. This perspective holds water, as paper currency such as jiaozi was an essential catalyst in this development.

Inspiration of jiaozi for future generations

Jiaozi, as the world's first paper currency, showcased to the global community the potential for items with negligible intrinsic value to serve as currency and fulfill crucial fiscal and economic roles.

In ancient China, the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties each issued paper currency, and when people discussed paper money, they often looked back to the jiaozi of the Northern Song Dynasty for historical insights. It is fair to say that the paper currencies of the dynasties following the Song were all influenced by the jiaozi.

During the Yuan Dynasty, Chinese paper money was observed with interest by knowledgeable people in Persia, Arabia, Europe, and other regions. The Travels of Marco Polo includes detailed accounts of the paper currency of the Yuan Dynasty. The Qing Dynasty's monetary theorist, Wang Maoyin, deeply studied jiaozi, and his insights on paper money were incorporated by Marx into Das Kapital. Even today, numerous foreign works on currency and textbooks reference the jiaozi from the Song Dynasty when discussing the history of paper money.

Of course, as the first form of paper money, jiaozi was far from perfect. The inability of private jiaozi to be fully cashed as promised, and the devaluation caused by the over-issuance of official jiaozi, both require our calm reflection. Beyond focusing on the "earliest timing," systematically summarizing the successes and failures of jiaozi is the best commemoration of this unique financial innovation in ancient China on the occasion of the millennium of the birth of official jiaozi.

The author is Wang Shen, assistant researcher at the Institute of Ancient History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

Liu Xian /Editor Zhang Rong /Translator

Yang Xinhua /Chief Editor Liu Xian /Coordination Editor

Liu Li /Reviewer

Zhang Weiwei /Copyeditor Tan Yujie /Image Editor

The views don't necessarily reflect those of DeepChina.