No change available

The value of a one-yuan coin or note will soon rise by 3 percent.

"No change! No change is available at the end of the year!" Ms. Liao shook her head at the customers in Guangzhou market complexes.

As a professional change exchanger, she has walked around the farmers' markets carrying a plastic bag every day since 1998. She comes to exchange change with retailers; each 100-yuan note is exchanged for 100 one-yuan notes or coins, minus a one-yuan service fee. At the beginning of 2007, the service fee rose to two yuan, but change still fell short of demand. The service fee rose to 2.5 yuan in September, and "it will rise to three yuan in a few days," Liao told Southern Weekend reporter last week.

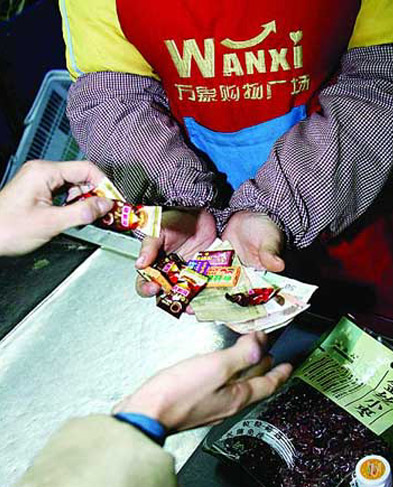

For small businessmen selling meat or vegetables this is surely bad news, but the change shortage also affects big supermarkets. Several Guangdong supermarkets offered a 6-yuan discount on groceries if the customer was able to exchange a 100-yuan note for small change. Many supermarkets in the southeastern coastal cities had to give their customers candy or tissues due to their lack of change.

Supermarkets give customers candy or tissues due to their lack of changes.

Subway companies have also suffered from the shortage of change. From October, in order to ease shortages, the ticket machines at Guangzhou subway stations refused to accept 20-yuan notes. Even banks have run short of change for several months, prompting the question: Where has the change gone?

Two-thirds stored by people

At the beginning of each year, boxes of RMB are sent across the country by train. Many people queue at banks to exchange large bills for change, but by the end of the year, the demand far surpasses the supply.

A manager with the People's Bank of China explained that the distribution of notes to coins is quite reasonable, and the supply of changes to banks is also adequate. However, people collect and store 60-70 percent of the available change each year.

People form a habit of saving change when they are very young. Children put coins into piggy banks that sit in their rooms through adulthood, often forgotten. When people get home at the end of the day, they often take all the coins out of their pockets and put them in drawers.

The bank manager claimed that people's storage of coins is the main factor behind the change shortage. The sharp rise of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) has forced fen coins out of the market, and worn-out Jiao coins are partly out of circulation. Therefore, one-yuan notes or coins are currently the main currency used to purchase small goods, but the volume of one-yuan notes and coins issued are far from satisfying the demand of circulation.

Counting fees impede change recycling

Banks charge counting fees for change exchanges.

Looking at the pile of change in their drawers, people may consider turning them into big notes, but when they arrive at the bank there is trouble waiting.

Mr. Zhang of Shenyang carried two bags of coins to a bank outlet in the city, having accumulated 37,000 coins, more than 600 yuan, over the past decade. According to the rules of the bank, there is a one-yuan service fee for counting every 50 coins. If he were to hand the money over to the bank, the service fee would amount to more than the total value of his 37,000 coins. "Does this mean I have to give my money to the bank for free?" Mr. Zhang helplessly took his money back home.

Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing banks have charged counting fees since 2005. These banks ruled that a 10-yuan service fee would be charged for counting every 1,000 notes, each valued at less than 10 yuan; 1 yuan is charged for every 50 coins.

After the rule was put into effect, the most affected were bus companies. In order to save counting fees, the Shenyang Bus Company handed out change to its employees as their wages. In the warehouse of the Qingdao Bus Company, piles and piles of paper change have rotted.

Despite this hindrance to change recycling, banks have no choice but to charge the counting fees. The Shanghai Industrial and Commercial Bank once calculated that if the bank accepted 2.6 million yuan coins each day, it would have to assign over forty employees to count those coins. The annual cost of counting would exceed 5 million yuan, putting banks at a loss even with the counting fees in place.

A retired employee of the Guangdong Bus Company complained: "RMB is always exchanged for equal value. Exchanging money is the duty of the banks. Why should they charge counting fees?"

How to solve the change shortage

The cost of printing Chinese currency has sharply increased in recent years, making it a financial burden for China to issue currency with a value of one yuan or less. The printing cost of paper currency with a value of 1 jiao is more than its actual value, and the cost almost equals the value for the currency worth 2 jiao. The paper currency is often destroyed after only four rounds of recycling.

In 2001, a pilot project to issue small-value coin currency was initiated by the Central Bank of China in Zhejiang, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Guangzhou and Shandong. The bank issued large quantities of coins into the market and gradually stopped offering paper currency valued at 1 yuan or less.

In fact, the circulation of coins with small value is an international trend. In 2000, the per capita possession of coins in Japan was 748 and 800 in Britain. However, the number was less than 80 in China, calculated based on volume of production, and only 10 in terms of turnover.

Most Chinese people are not used to coins and do not like to use shabby paper currency of small value. They usually keep the standard currency with a minimum value of 1 yuan for small transactions.

"The banks must prepare enough change and the Central Bank of China should guarantee the paper change can satisfy the actual need of transactions," said an economist Mao Yushi.

Banks believe that electronic currency should be promoted in China, as 80 percent of payment in developed countries is finished through electronic currency. The professional money exchangers must be banned, but the banks should also stop collecting counting fees. Additionally, the prices of commodities should not end in a number that would make it difficult to produce change, some business people said.

However, the best method to help as quickly as possible is to simply circulate coins and handle paper currency carefully.

More about RMB

(China.org.cn by Zhang Ming'ai and Yang Xi, November 20, 2007)