Chinese urban planning has fallen victim to a recent economic juggernaut, unwittingly turning into a “modern enclosure movement.” The land squeeze pitted development zone builders against each other in the midst of a real estate boom. They make wild land grabs, driving farmers away as their properties are converted into walled industrial complexes.

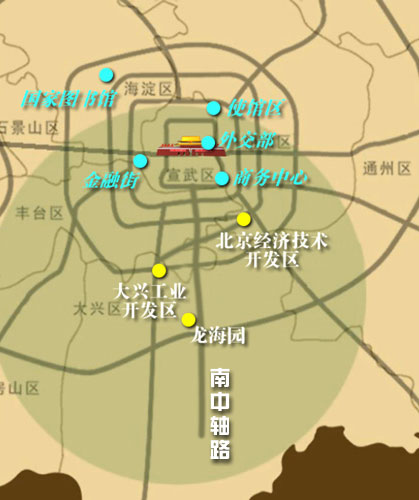

In 2000, the Beijing Municipal Committee of Urban Planning initiated a plan to build an industrial hub linking Beijing, Tianjin and Tangshan. Under the plan framework, Daxing District situated at the suburb of south Beijing emerged as a promising and attractive location for industrial development zones.

Since then, a total of 100 industrial development zones have taken over the district, quickly encroaching on large chunks of farmland. However, scores of buildings were soon left idle because of scarce investment.

“In the past, we downplayed well-rounded scientific planning. We only considered economic development as the paramount task. At that time, the walled complexes containing factories were common here,” said Wang Wanxing, a superintendent with the Land and Resources Department of the Daxing District Government.

In 2003, the area was targeted for a radical shakeup from the central government in order to protect farmland from urban encroachment. Land was reclaimed from the zones and reverted to fields. Adapting to the policy change, sly developers changed their names or merged with larger zones to evade the regulations. In this way, the factories could maintain their presence in the zone.

These evasive actions essentially nullified the government’s efforts, so on March 25, 2004, the Ministry of Land and Resources resolved to show its teeth by strictly prohibiting merges within the development zone.

In response, the Daxing District Government conjured up a program known as the “New Media Base.” The program came as a solution to protect misfit industrial development zones from the purge by incorporating them into the base. Lazarus-like, the zones seemed to find a way of rising.

Other Herculean constructions in the works included the Jing Nan Logistics Base and the Beijing International Printing and Packing Base within a stone’s throw from Weishanzhuang Village. The base is just another version of a development zone, but enjoys more favor and privileges in policy.

Their differences also lie in the size and function, as the base is bigger and more diverse. The New Media Base, for example, will bring together industry, commerce, and accommodations over a span of 333 hectares.

Traditionally, land in the development zones is allotted for industrial use while the base can diversify the land use. Compared with a development zone, a base is approved by the state or the provincial government and thus seems much safer under their protection.

The base developers told China News Weekly they were quite confident in the base’s prospects, saying they would sweeten the deal with the investors who would stand a chance to get a slice of hefty governmental grants.

“There used to be a plenty of farmland in the village, but now I even don’t have a small vegetable patch,” said a 64-year-old villager brimming with rage. The old man scraped a living out of a monthly governmental allowance of 300 yuan.

In Dazhuang Village under Daxing’s jurisdiction, the farmers have been almost completely driven away from the land they lived on for generations. Last year, the last empty lot in the villager’s land inventory was snatched by Jingnan Logistics Base to complete its ambitious blueprint.

(China.org.cn by He Shan, December 14, 2007)