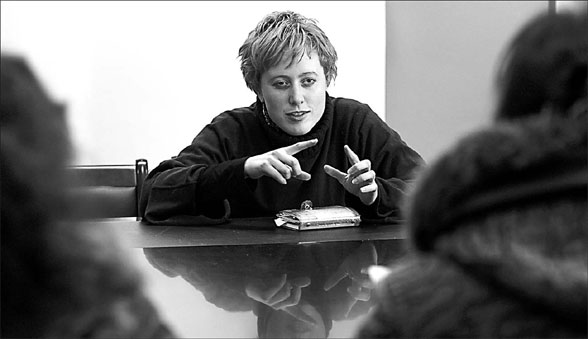

Kate Kinahan is one of very few foreign community mediators in China. Yang Xi

Kate Kinahan knows how to defuse tense situations - often her very presence is enough. When two families in the same Nanjing apartment block started feuding over noise levels, the local community mediation team was called in.

The quarreling neighbors fell silent as the young blond European woman stepped into the fray and began speaking to them in fluent Chinese.

Soon the dispute was forgotten and the neighbors were asking the soft-spoken foreigner where she was from.

"South Africa," said Kinahan, 27, the only foreign community mediator in Gulou District, in Nanjing, capital of East China's Jiangsu province, and one of an unknown but probably tiny number in China.

Since studying law at Nanjing University from 2003 to 2007, Kinahan has been combining her knowledge of China and self-effacing exotic appeal to help allay the growing social pressures of her adopted city. Speaking in Chinese, she explains: "Mediators can assuage the deeply felt concerns of people and improve their communities."

Her path to mediation began before she arrived in China and she sees a need for greater mediation in the international community too.

"Many foreigners know little about Chinese culture and hold extreme prejudices against China. One can only understand things in China better after having lived here for several years. What is unreasonable to outsiders can make sense to the people here," says Kate, who arrived in the southern Yunnan province to learn Chinese in 2001.

She persuaded the noisy neighbors to see things differently. One of them, 51-year-old Pan, says: "Kate told us not to have negative expectations and to try to trust each other. I had been retaliating to the problems, but her words made me see sense. She told us to collect evidence in case legal intervention was necessary. I had never thought of that."

Kinahan first saw the mediation system in action when she visited a classmate's home in rural Jiangxi province as a student.

A man had seriously beaten his wife and village cadres, who serve as mediators, came to persuade the man to stop. "The wife said she was afraid her husband would beat her again after we left," she says. "Rural people desperately need legal information to protect themselves. Local mediators complement legal workers in areas with scarce legal services."

China's community mediation system was set up at the foundation of People's Republic in 1949. It went into decline in the two decades of reform and opening since the late 1970s, but was revived earlier this decade to deal with a rise in conflicts caused by a rapidly changing society, says Wu Yingzi, a professor of mediation with Nanjing University.

Booming Jiangsu province is seeing rises in marriage and family problems, which are sometimes caused by relocation, pollution and redundancy, says Zhang Xinmin, deputy-director of Jiangsu Provincial Judicial Department.

Jiangsu is taking a national lead in improving the mediation system at county, city and district levels, pooling community, administrative and court mediation resources to ease the burden on courts, says Zhang.

A Christian who grew up in rural South Africa and was heavily influenced by her English immigrant parents, Kate sees a natural role for herself in the system.

"When I was young, my parents ran a kindergarten during the apartheid system when blacks and whites went to separate schools. They tried to improve understanding by accepting both black and white kids.

"My friends were black. I hugged them in public and I am used to being stared at, so I'm not uncomfortable as a mediator in China," she jokes.

Before coming to China, she experienced community development work in Kampuchea and Australia, where she learned the importance of listening.

"I remember NGO members getting irritated when they asked a village what was needed most. The villagers said a football field, but the NGO members were trying to explain the need for a medical service," she says.

"Eventually they helped build a football field and something unexpected happened. The villagers loved football so much that the entire community gathered there. It was on the field that they discussed medical problems, and they decided to tackle it by themselves.

"If you want to help people, you must work with them and be a friend."

Kinahan deals with the minor mediation cases involving community quarrels and is yet to graduate to major social issues such as relocations.

But her work is made easier by the public acceptance of mediation and its avoidance of costly lawyers, says Yao Qiming, deputy head of Nanjing Gulou District Judicial Department.

The district is experimenting with "community law classes" and legal workers, including Kinahan, will lecture the public on issues such as property, marriage or inheritance, says Yao.

Kinahan recognizes the public appreciation. "The mediation service reaches every corner of the country, providing a free service - a rarity in many countries. It's about spotting nascent problems and intervening quickly.

"But I'm still a student and not an expert," she says, indicating the English book on law open on her desk.

Her modesty is evident. Dressed casually in a light black sweater, jeans and sneakers, she cycles to work, a 20-minute journey.

Complimented on her fluent Chinese, she smiles and responds: "No, it's far from good."

At home in her rented apartment, she posts song lyrics on her blog, which also carries photos of her big family in South Africa.

"My parents support my life. Their support is important to me," she says.

Her work in China has changed her view of the world. "Chinese pay great attention to poverty problems as the welfare system is not that advanced. People work hard to improve living standards," she says.

"Sometimes they give up their personal ideals for the collective. For example, many criticize the family planning policy in China, but there is a reason for it. People understand it's a transition stage in development and they follow it for the country.

"If you want to help others, first you should put aside your values and beliefs for a while and try to see things as they do."

In the eyes of her colleagues, Kate "likes thinking and analyzing". "She often enlightens us with a different cultural perspective," says Xue Tao, director of Haining Street judicial office under Gulou District Judicial Branch. "She will first stress personal feelings, when we will consider social influences when dealing with a case."

Asked whether her future is tied to China, Kinahan says: "I want to settle down in China... Sure I could marry a Chinese and it will also help me know Chinese culture better.

"If something is worth doing such as helping those without a voice, it deserves a lifetime."

(China Daily February 21, 2008)