| Home / Books & Magazines | Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

| Larger than Life |

| Adjust font size: |

Chinese writer Wang Xiaobo (1952-1997) struggled all of his life to get his books published and distributed. Then, he died. On April 11, 1997, Wang suffered a fatal heart attack, leaving his novella Black Iron Apartment unfinished on the desktop in his Beijing home. Ironically, the sudden death of this previously little-known author grabbed public attention and copies of his novellas and unfinished manuscripts have been flying off of shelves since. Since the year after Wang's passing, he has been hailed as not only a brilliant writer but also a free-thinking intellectual, sharp-eyed social commentator and a true romantic. So, during every April since 1997, Wang's readers have organized commemorative activities to honor the passing of the young writer who once called himself "a peculiar pig" who thinks independently and acts differently. Scads of young writers labelling themselves as Wang's protgs are now emulating his writing style in their novels and essays, and Wang Xiaobo fan sites are popping up all over the Internet. And some readers have organized gatherings where they recite paragraphs from Wang's works.

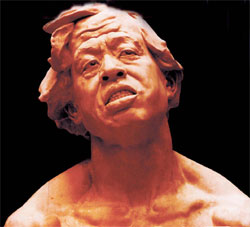

And most recently, Zheng Min, a young sculptor in Guangzhou, created a larger-than-life nude sculpture of his idol Wang Xiaobo. The piece has caused a stir among art circles, media and the general public. A series of commemorative events were launched throughout the last week, heralded by Wang's widow, famed sexologist Li Yinhe. And these events haven't been confined to China's metropolises, such as Beijing and Shanghai. They have also run in rural Longchuan County, in Southwest China's Yunnan Province, where Wang spent three years in the fields toiling alongside local farmers during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). "With every passing year, the commemoration has been turned into a sort of sacred ritual. And Wang's readers and fans have virtually lifted him to the status of a cultural icon," said Huang Jiwei, a writer and publisher in Beijing, who said Wang is "simply a youth devoted to the letters". However, according to China Youth Daily columnist Bi Wenchang, "None of these commemorative activities are government-sponsored or commercially oriented. They have been carried out spontaneously by Wang's fans and readers who really love reading his works." "Wang's works not only won the hearts of numerous young Chinese 10 years ago but also countless followers of all ages today, while many of his contemporaries have been forgotten or ignored. In that sense, Wang has withstood the test of time," Bi said, adding that, "this is a significant phenomenon that deserves attention". Born to an intellectual's family in Beijing in 1952, Wang's life was full of twists and turns. The author started working as a farmer in the late 1960s before going on to become a teacher in the countryside, a technician and a university lecturer. For the last five years of his life, he worked as a freelance writer. Unlike his contemporaries who wrote as a profession, Wang did not graduate from a school of humanities or liberal arts. Nor did he belong to any writers' association. And Wang wasn't a prolific writer. He penned only a handful of novels, novellas, essays and film scripts, in addition to co-authoring with his wife an academic report about China's gay community. Wang's best-known novel series, The Time Trilogy which includes The Golden Age, The Silver Age and The Bronze Age caused a sensation when it was published shortly after his death. In writing The Golden Age, Wang drew upon his own experiences. The story, which is riddled with Mark Twain-esque humor and satire, tells the tale of Wang Er (literally, Wang Number Two). Wang Er is a well-off urban student sent to be re-educated in the countryside of Yunnan Province, where he runs off with a married doctor.

In 2015, Wang depicts another Wang Er. This version of Wang Er is a painter whose paintings are so stridently fractal that they make people dizzy. Sent for re-education during the "cultural revolution", he readily admits his stupidity. But he is undone when a female guard takes a very twisted interest in him. Yet more readers know and admire Wang Xiaobo as a sharp-eyed essayist. Heavily influenced by such Western intellectuals as Italo Calvino, George Orwell, Marguerite Duras, Milan Kundera and Bertrand Russell, Wang advocates rational and scientific thinking, and battles against mind imprisonment in his columns. Many people know Wang for his frank, often antic, treatment of sex. But what appeals more to his readers are his artful and engaging narrations, penetrating satires, unique and refreshing sense of humor, and his mind-liberating commentaries. "Wang often writes in a hyper-free state of mind. He looks deep into the darkness and complexity of human nature. And almost at the same time, he churns out penetrating views about worldly affairs in a fast-changing China," said Zhang Yiwu, a literature scholar with Peking University. Working outside of the establishment and thinking out of the box, Wang offers the readers a voice that is totally different from mainstream intellectuals and writers, Zhang said. "What Wang focuses on in his writings may be of little significance today, but his unique way of thinking continues to illuminate Chinese writers and readers," he concludes. "Why has he (Wang Xiaobo) attracted so huge a following over the last decade? I think it is because of the universally respected, humanistic and free spirit that imbued in all of his works," Li Yinhe told local media. Recently, US-based Suny Press published three of Wang's novellas, including The Golden Age, East Palace, West Palace and 2015, under the title Wang in Love and Bondage. "Personally, I think Wang's novellas are easy for Westerners to read. The 'trendy' subject matters, such as homosexuality, the post-modernist style and dark humor found in his works are what Western readers are familiar with," Zhang Hongling, who translated the book along with Jason Sommer, was quoted as saying by local media. The publication of this book for English-language readers is very significant, Zhang said. "It will at least change the deep-seated view that all modern Chinese literary works are very depressing to read," Zhang said. "Wang's humor and joy will surely impress overseas readers." (China Daily April 24, 2007) |

| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

|

| Related Stories |

|