China.org.cn: Which works of yours have been translated into foreign languages? Which ones would you most want to be read outside China?

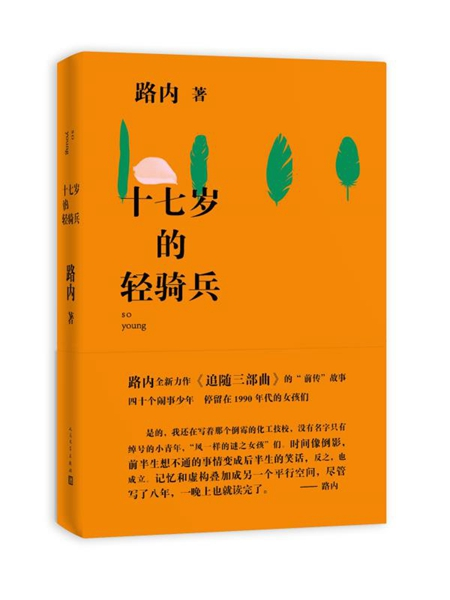

Lu: "Young Babylon" and "A Tree Grows In Daicheng" have been translated into English. "Cibei" (lit. "Mercy") has been translated into Arabic and Bulgarian, and a Korean version is waiting to be published. The English translation of "Mercy" is in progress.

I suppose [I most want foreign readers to read] "Young Babylon" and "Mercy." The latter is a story spanning almost 50 years, and offers some new insights on China, [politically] a bit on the left and a bit on the right. Also, I want to discuss in the novel whether Chinese have a sense of religious faith. Chinese are known to be atheists, but there are actually a large number of Christians and Buddhists. Buddhism has a lot of secular elements, and in that sense, whether that can constitute a sense of spirituality in the Chinese people and whether that can make them happy and lead them to do good – that is what I want to discuss in the novel.

"Young Babylon" is different. There are many politically incorrect things in the novel, and I want to see how foreign readers respond to that.

China.org.cn: What do foreign readers think of your novels as far as you know?

Lu: For Chinese writers, especially novelist, it is very diffcult for them to be read widely outside China. I delivered a speech at the Frankfurt book fair in 2016, where I found most of the people in the audience were just passers-by. But there was an old Austrian man who brought with him two of my Chinese books for autograph. I asked him if he read Chinese. He said no, but that he had read the English translation of "Young Babylon" and flew from Austria to meet me. I was moved. If I can claim to have readers in Europe, that man was the first I knew.

China.org.cn: In your view, how are contemporary Chinese novels received in foreign countries in general?

Lu: Things are better with the older generation of novelists. They often work with a good publishing house that does better promotion work. As for their writings, I think they can meet foreign readers' expectations about China at the time they wrote. When foreign readers approach Chinese literature, they bring with them some preconceived notions about China, which can match with stories written by Chinese novelists from the older generation. This is a problem for novelists in my generation, and not only in consideration of foreign readers, but those in China as well. That is, does our writing reflect the real world in contemporary China? If the novels do not even match up with what Chinese readers understand about the reality in this country, then it would be even more problematic for foreign readers.

China.org.cn: How do you look at the relationship between your fictional writings and the real world?

Lu: It's impossible for a writer to catch up with [what's happening in the real world], as the world is changing too fast and China even faster. For example, this year marks the 10th anniversary of the Wenchuan earthquake, but there is no notable novel about the quake. The quake is too huge a thing that is impossible to write about from the periphery – you have to go to the core of the events to produce great literature.

But for writers who are in their 50s, for instance Mo Yan and Yu Hua, they wrote about things from their time. It is difficult to write from the periphery of the [fast-changing] times and values.

China.org.cn: So is it a good time for great works in China now?

Lu: First of all, there are nothing of interest or intensity today. The classic works published in the 1980s and 1990s are tremendously powerful, but that power is lost nowadays. For writers who are born in the 1970s or after, everything is about entertainment and few have real substance.

However, it is [still a good time for great works]. The world is waiting for Chinese writers to produce a great novel. China is a very special country, with its special experiences and values. So if we failed to deliver on that, we novelists are actually the ones to blame.

China.org.cn: Do you personally expect to contribute one of those great works? What would be your timetable for that?

Lu: Of course. The pursuit of great literature is always there, it is there until the day I die. But I won't be fixated on that, or become self-satisfied with what I already have.

I haven't set a personal timetable, but I hope to write a great novel before I turn 50. The novel I am working on now could be published by 2020 if all goes well. I hope it'll be a great novel. And I hope from then on, every book of mine are headed for greatness.

China.org.cn: Did you have lesser expectations for your previous novels, such as "Young Babylon" and "Mercy"?

Lu: Those two are not bad, but when it comes to a work being recognized as a classic, Chinese writers often come across two problems. First, even if Chinese writer do not reach out to European and American readers, they can be masters in the Chinese literary field as China is such a big country. But when Chinese literature stands on the same stage with writers from all over the world, it suddenly becomes a minor literature. If your writing is too old fashioned, it won't be read in China, let alone the world.

There's a peculiar thing about Chinese literature, that too much of it is about farmers. It has always centered on people's hunger – it is an important subject in a certain period of time, but not any more now.

China.org.cn: Since its publication, "Mercy" has been compared to Yu Hua's "To Live." What are your thoughts on that?

Lu: If you must compare, I think "Mercy" is more like Yu Hua's "Chronicle Of a Blood Merchant."

Every writer inherits something from the previous generations of writers. I acturally was reading Lu Xun's "The True Story of Ah Q" when I wrote "Mercy."

China.org.cn: Chinese writers born in the 1970s and 1980s are often compared with the older generations, and some argue that the younger generation are not living up to the literary achievement of those who are born in the 1950s or 1960s. Do you agree?

Lu: For Chinese writers like Ge Fei and Yu Hua, they experienced all the literary movements since 1979, but writers like me who did not begin writing until around 2008, we have never experienced any. When I began writing, I felt like the room was already packed with furniture and it was hard to move around. I had to find a space to put in my stuff.

Writers who are born in the 1970s and 1980s indeed cannot compete with the previous generation, either collectivley or individually. But if you say we don't set our minds on pursuing great literature, that's not true. It is not a problem unique in China. In American literature for instance, writers now are nothing compared to Faulker and Hemingway and their generation. The world is faced with the same problem.