By Zhang Bin

Following the 1997 Asian financial crisis, much

progress has been made towards East Asian cooperation. To date this has included

a strengthening of monetary and financial cooperation. Meanwhile the debate

has been increasing on future options for regional monetary and financial

cooperation. There have been significant new developments particularly in

the fields of economic intelligence and crisis management.

In general, regional surveillance

mechanisms exist to provide timely and accurately analysis of macroeconomic

information and early warning of a crisis. The systems rely on peer monitoring

and review and depend in no small way on information disclosure by member

states.

In October 1998, the Finance Ministers of the Association

of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) signed the Terms of Understanding that

established the ASEAN Surveillance Process (ASP). Based on principles of peer

review and mutual interest among members the overall purpose of the ASP is

to strengthen policymaking capacity within ASEAN.

Surveillance Activities

Under the ASEAN Surveillance Process, member countries

have agreed to strengthen regional macroeconomic and financial cooperation

through three key activities:

(i)

Monitoring global economic and financial developments

and analysing their impact on ASEAN.

(ii)

Monitoring and exchanging views on the economic and

financial development of member states.

(iii)

Discussing and formulating through a peer review process,

a response to any adverse developments or issues arising from the monitoring.

Surveillance Concerns

ASP is already operating. Whether or not it can be really

effective is still a matter of concern due to three factors:

(i)

There is a potential weakness in the lack of transparency

in economic and financial data and reports published by ASEAN countries. Governments

in developing countries are often reluctant to provide definitive information.

They may prefer to view economic data as a strategic tool rather than as a

something to be published for general use.

(ii)

The Realpolitik, that is to say the politics of power

and expediency rather than ideals, is a constraining factor within ASEAN.

There is considerable asymmetry in economic size and development among ASEAN

countries. There is an agreed principle of non-interference in the domestic

affairs both economic and especially political, of other members. This militates

against effective implementation of the regional surveillance process. For

instance, criticism of another country’s economic policy however much deserved

would likely be considered inconsistent with the “ASEAN Spirit”.

(iii)

Although there is support from the Asian Development

Bank (ADB), it is difficult for ASEAN to establish and maintain an effective

surveillance mechanism. The Secretariat is under-funded and too small and

ASEAN itself is a relatively loose organisation.

Nevertheless ASP is still an important development. If

it were to prove effective in practice it would augur well for the development

of a similar surveillance mechanism within an East Asia 10+3 co-operative

framework. That is to say in the context of the ten ASEAN nations + China, Japan and the Republic of Korea.

In fact, a financial surveillance mechanism is already taking shape within the 10+3

framework. The first peer review meeting was held alongside the May 2000 annual

meeting of the ADB in Hawaii. The 10+3 Finance

Ministers’ meeting reconfirmed the goal of establishing an early warning system

in East Asia and it was agreed to work

towards this.

Crisis Recovery

The Asian financial crisis has strengthened

the recognition by East Asian countries that it is imperative to establish

regional financial co-operative mechanisms. Financial rescue mechanisms are

particularly important. Japan first proposed that an

Asian Monetary Fund should be set up. However this fell through due to lack

of support. Real progress was then made in regional monetary swap arrangements.

At the ADB annual meeting in Chiang Mai, Thailand in May 2000, Finance Ministers

from 13 East Asian countries agreed to establish a monetary swap arrangement

to be used to help tackle any future financial crisis. This regional financial

Cupertino (co-operative networking

mechanism founded in policy) will provide for bilateral monetary swap and

repurchase agreements between participating countries in the region. This

offers a means of protection for the currencies in the event of a speculative

attack.

The Chiang Mai Initiative is generally

considered to be a milestone achievement on the road to an Asian regional

monetary and financial Cupertino. East Asian countries

have already signed a series of bilateral monetary swap agreements following

Chiang Mai.

However, the Chiang Mai Initiative

still contains many elements that are still merely symbolic and further development

will be necessary. It will also be necessary to increase the scale of the

monetary movements in the future.

Long-term Prospects

The process and goals of an East Asian

monetary and financial Cupertino must be closely integrated

into those of any wider East Asian cooperation. Long-term goals for cooperation

in the region as a whole are needed to provide the context for a monetary

Cupertino. A report by the East

Asia Vision Group has clearly proposed the establishment of an East Asian

community.

Their vision of an East Asian community

is not for another European Community. It is not their wish to work towards

a supranational organisation at regional level. Rather their aim is one of

gradually deepening Cupertino and co-ordination among

the countries of the region. They wish to see further establishment of co-operative

mechanisms in the economic, political, social and cultural fields. For example,

in the area of trade and investment their ultimate goal is the establishment

of a free trade and investment area.

As for monetary and financial

Cupertino, in

the report of the East

Asian Vision Group entitled “Towards an East Asian Community, 2001” the prospect of an eventual single currency is left open. The report merely acknowledges

the possibility that a common currency area could be established given favourable

and mature economic, political and social conditions.

Monetary unification would mean the

abandonment of monetary sovereignty by member countries coupled with a degree

of political integration. This presupposes the existence of strong political

will for closer ties in East Asian countries. However, at present, there are

just too many political and economic differences amongst East Asian countries

so the conditions necessary for monetary unification are not yet in place.

Currently it would be both difficult

and indeed unrealistic to seek to open discussions aimed at monetary unification

for the whole of East Asia. Such discussions would

become feasible if the political obstacles were to be dismantled against a

background of a progressive narrowing of differences in levels of economic

development. This has to be seen as a remote goal probably requiring decades

for realisation.

Proponents of regional monetary unification

argue that if monetary unification in East Asia is adopted as a long-term

goal, planing for this future should commence now. A step-by-step approach

is advocated.

Monetary unification could first be

achieved at a sub-regional level. This could then be gradually extended to

the whole East Asian region. Considering the situation in the region as it

is today and taking account of the potential for development, two possibilities

for common currencies could be thought feasible. One potential grouping would

be within ASEAN and the other centred on mainland China. They would not be mutually

exclusive.

The ASEAN Five

The first of these common currency

possibilities resides within the core countries of ASEAN namely Malaysia, Thailand, Philippine, Indonesia and Singapore (the original ASEAN Five).

Smaller countries may be more inclined

to join a monetary union as they have less to lose. These five states are

already broadly similar in their level of economic development, fiscal deficits,

inflation rates and the like. They have accelerating economic integration

and they share a common strong political will for cooperation. They already

have a relatively sophisticated co-operative mechanism in ASEAN. In many essential

features, the core countries of ASEAN satisfy the criteria for a workable

common currency. They could then progress to closer monetary union at a later

date.

The Brunei currency has special a

relationship with the Singapore dollar so Brunei might also join in with the

first group of countries to adopt a common currency within ASEAN.

The new members of ASEAN (Vietnam,

Laos, Cambodia and Burma) are separated by rather greater differences. They

are relatively backward in their economic development and subscribe strongly

to principles of political sovereignty and non-interference in the domestic

affairs of others. It will be a long time before they would be in a position

to adopt a common currency.

China

The second of the most likely common

currency possibilities centres on a reunified China. Already Hong Kong and

Macao have been returned to China. A free trade area to embrace the mainland,

Hong Kong and Macao would be conducive to monetary unification. Economic and

trade contacts across the Taiwan Straits are strengthening and mutual economic

dependency continues to grow.

In the economic field we find the

full and necessary conditions for monetary unification. Once political reunification

has been realised, the opportunity for and necessity of monetary unification

will surely increase.

The Chinese economy is expanding

rapidly and China’s economic strength will continue its growth. By 2030 China is

expected to be the largest economy in the East Asian region. In the light of

this, the Chinese RMB could well become the leading currency in East Asia. This

would be a major influence on the direction of regional monetary cooperation.

The Next Few Years

We can draw some points on forthcoming

developments in East Asian cooperation from the 2001 conference in Brunei:

(i)

At present and for next few years, the main work for East Asian

cooperation remains to stabilise and strengthen mechanisms to facilitate

political consultation and dialogue in the region. It is still too early to set

long-term goals for East Asian cooperation.

(ii)

Conditions are still not right for promoting a free trade and investment

area for the whole East Asian region. Presently it is sufficiently ambitious to

look towards coexistence coupled with the development of multi-level co-operative

mechanisms.

(iii)

The negative effects of the Asian financial crisis are still being felt.

The main focus of some East Asian countries lies in regaining the momentum of

their economic development.

East Asian cooperation does not involve a clear

political objective like Europe It is founded instead on existing benefits

which have proven to be both in the interests of the economic development

of individual nations and also conducive to regional peace and stability.

For the time being, East Asia does not have the

political basis or impetus for significant regional integration. Therefore when promoting regional functional cooperation,

the most important thing is to build on those opportunities for cooperation

that advance the cause of regional economic development.

The foundations of and impetus for regional integration

can only be developed gradually through the development of co-operative mechanisms.

Cooperation can move forward more easily in some areas than in others.

East Asian cooperation under the 10+3 framework

has already started. This is a process that is unlikely to be reversed. In

the near future, we might see consideration given to the early establishment

of a secretariat for East Asian cooperation. Such a body would be able to

co-ordinate the process of cooperation and investigate the potential for future

developments and closer working. What could be achieved?

(i)

Strengthen Macroeconomic

Cooperation Mechanisms

East Asian monetary and financial stability is based on economic stability and

development in the region. The key item on the agenda of East Asian

monetary cooperation should therefore be to strengthen mechanisms facilitating

macroeconomic dialogue and co-ordination.

East Asian Finance Ministers’

meetings should have a strong focus on agreed key issues in economic

development and related fields. The meetings should be institutionalised and

held twice a year. The consensus reached should influence the economic policies

of every country in the region.

(ii)

Strengthen Monetary and

Financial Rescue Mechanisms

The aftermath of the Asian

financial crisis is still with us and the danger of another financial crisis

in East Asia remains. The most urgent task is to further strengthen and quicken

the development of regional financial rescue mechanisms.

The Chiang Mai

Initiative and the monetary swap arrangements were important developments in East Asian monetary cooperation. For the time being this is the best option for a regional financial rescue mechanism and all the bilateral

swap agreements should be put in place as soon as possible. These bilateral

agreements should later be evolved into the basic framework for future

East Asian monetary cooperation.

(iii)

Strengthen Financial Surveillance

and Early Warning Systems

Financial surveillance

is a responsibility of government. In order to maintain the stability of domestic

financial markets and prevent the recurrence of financial crisis, governments

in the region should work to improve their domestic economic policies and

strengthen their domestic financial systems.

In the event of a developing

crisis, interactions across the region carry risks of “contagion” meaning

in this context the spread of the crisis from one country to another. This

emphasises a now imperative need for collective surveillance feeding into

an early warning system at the regional level.

Surveillance and early

warning system are closely related. At present, it would be unrealistic to

seek to set up a specialised regional institution. Efforts should be focused

on the establishment of co-operative mechanisms to operate among central banks

in the region.

A fully functional co-operative

agency should be set up within each central bank. This would enable permanent

liaison and cooperation networks to be formed in East Asia.

In addition, we could

consider the establishment of a framework of East Asian financial surveillance

and early warning mechanisms enabled to issue economic and financial indicators.

This would serve to provide timely and reliable information to help inform both

government policy-makers and the markets.

(iv)

Explore Regional Exchange

Rate Co-ordination Mechanisms

Mechanisms for regional

exchange rate co-ordination require a more advanced level of co-operative

framework. They will follow only on the heels of deepened financial cooperation.

East Asia does not currently

satisfy the conditions necessary for an effective exchange rate co-ordination

mechanism. After the Asian financial crisis, many East Asian countries and areas have abandoned

their dollar-peg systems and rigid exchange rate policies. They now rely instead

on a floating rate.

East Asian exchange rates are still

prone to be affected by any sharp fluctuation in the yen. And what is worse,

East Asian countries have no solutions in place to deal with these knock-on

effects. The situation has seriously undermined the stability of the East

Asian economies. Exploration of regional exchange

rate co-ordination mechanisms must be on the agenda for East Asian

monetary cooperation.

East Asian currencies have therefore

proved to be unsuitable for pegging to either the dollar or the yen. It would

be unrealistic to think of introducing an East Asian Currency Unit for many

years yet.

East Asia should focus instead on

strengthening macroeconomic co-ordination and exploring a floating-rate

target-zone scheme for the regional currencies. Based on principles of cooperation

and commitment, each country or area would propose its own upper and lower

limits within which its currency would float for a specified period of time.

This is the target-zone. This could be conducted under the surveillance of the

regional co-operative mechanism. Target zones might be adjusted in some special

cases but this would have to be notified to the other countries in advance. If

necessary, the range of adjustments could later be narrowed through regional cooperation.

(v)

Explore the Feasibility of a Monetary

Fund

Though the Japanese proposal

for an Asian Monetary Fund (AMF) has been put on the back burner, worthwhile progress has been made within

the framework of the Chiang Mai Initiative. A goal of a regional money swap

agreement has been identified and already there are bilateral monetary swap agreements in place to pave

the way.

A money swap mechanism would clearly

not be the ultimate goal of East Asian monetary cooperation. Fuelled by the

Chiang Mai Initiative, the debate about a regional fund has warmed up again.

The need for economic development is

just as strong as ever and there is no reason at all to close the door on the

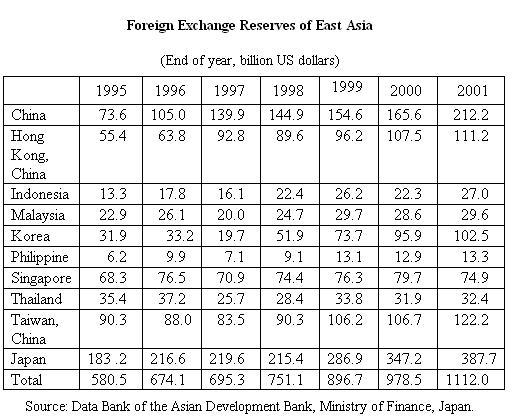

AMF concept. Further exploration of AMF feasibility should be encouraged. At present, the East Asian economies have

substantial foreign exchange reserves (see table below) and the funds to

support an AMF would not be a problem. Meanwhile, objections to the

establishment of an AMF from within the East Asian countries and from the wider

international community seem to have diminished.

The road to an Asian Monetary Fund

It could be said that full

implementation of the Chiang

Mai Initiative would go some way to lay the foundations for the establishment

of an AMF. However, the road to AMF would depend on:

(i)

Further

implementation of the Chiang Mai Initiative

and the consequent development of East Asian monetary cooperation mechanisms.

(ii)

Actual

need for a regional monetary fund and other regional co-operative developments.

(iii)

Development

of comprehensive East Asian cooperation. (as evidenced by the negation of the

1997 Japanese proposal).

The author is an associate research fellow with

the China Institute of International Studies

(china.org.cn September 16)