| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

| Drinking Their Fields Dry |

| Adjust font size: |

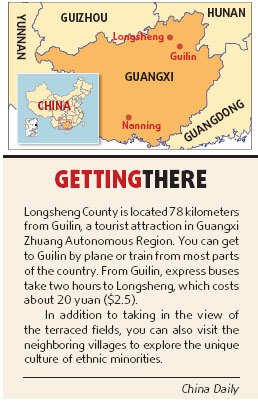

The terraced fields of Longsheng, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, have sustained the ethnic monority farmers for 700 years. They now stand threatened by the heavy influx of tourists. -Yu Xiangquan "In May this year, the Dragon Backbone alone - the core area of the 700-year-old terraced fields - drew 50,000 visitors, including 10,000 from overseas," he says. Tourism indeed has contributed much to the county's revenue, Yang says. Longsheng's tourism earnings had jumped from 234,100 yuan ($30,864) in 1999 to over 11 million yuan ($1.45 million) in 2006, accounting for nearly 10 percent of the county's total revenue. Meanwhile, the family inns run by local farmers within the Dragon Backbone area frog-leaped from three with 45 beds in 1992 to the current 112 with more than 3,000 beds, providing handsome earnings to the locals, Yang says.

In comparison, the terraced fields created by the Hani people in Yet there is one thing the Hani terraced fields cannot match: accessibility. While the Hani fields are hidden deep in the However, says Ben Huangwen, deputy head of The easy access brings flows of tourists, many of whom stay overnight to wait for better photographic opportunities. That has resulted in a water shortage, says Ben. "The water consumption has multiplied as tourists are several times the local population," he says. The core area of six villages has a total population of 7,800, while the tourists expected this year number 300,000. "Hence the contention of human consumption of water with the irrigation." To satisfy this consumption of water, the locals have to compromise what is used for irrigation. "The terraced paddy fields used to be inundated with water all year round," says Ben. "Now the farmers won't flood the fields until the transplanting season so as to save the water."

After an investigation of the terraced fields, Duan Xiangfeng, an engineer with the Guangxi Planning Academy of Land Resources who has made four trips to the six villages, noted down 577 sites of collapse involving more than 25 hectares. There are two reservoirs near the Dragon Backbone, says Duan, but they cannot provide adequate help. "They are long out of repair and suffer serious leakage, with one third of the designed capacity of water conservancy leaking away," she says. Also collapsed is the traditional farming system, Duan says. As the farmers are preoccupied with receiving tourists, from whom they earn far more than from rice growing, there is a lack of field management. "Local villages used to have people tending the ditches blocking the surface runoff when there is rainfall," she says. "Now those ditches are deserted with little tending of them. When a storm hits, the surface runoff easily runs wild into torrents to destroy the fields." Local officials turned to land authorities for help and the Regional Department of Land and Resources of Guangxi has incorporated the preservation of Longsheng terraced fields into its land consolidation program. The program aims to consolidate fragmented and underused land, reclaim wasteland or land damaged by mining or natural disasters, and develop unused land resources with the prerequisite of guarding against desertification and soil erosion. "We are obliged to preserve farmland," says He adds that the department plans to put in 30 million yuan ($3.96 million) for the Longsheng project, which involves a total area of 795 hectares of terraced fields. That is how Duan and her colleagues came in, and produced a plan for the consolidation of the terraced fields after a year's work. But Duan has found the challenge "more formidable" than she could imagine at the beginning. "It's not a big deal to do the engineering work, to repair the fields, build roads, restore the vegetation on top of the hills, dig the ditches and rejuvenate the reservoirs," she says. "But the tough question is how to sustain it." If the farmers continue to prioritize tourism and neglect farming, she wonders if the terraced fields can be preserved. Deputy Director Cao also felt that the project is unprecedented. "While trying to preserve the farmland," he says. "You have to preserve the terraced farming culture as well." This, says Luo Ming, chief engineer with the Land Consolidation and Rehabilitation Center under the Ministry of Land and Resources, is actually "the most creative and brilliant spot of this project." The nationwide land consolidation program, initiated in the late 1990s, is to "preserve the country's 120 million hectares of farmland," says Luo. "But fundamentally speaking, farming is a culture. You cannot preserve a land without preserving the culture that has been integrated with the land." In this sense, she says, Guangxi is leading the country in displaying the essence of land consolidation. Cai Yunlong, professor of land management from Jeffrey Soule, director of the American Planning Association's outreach and international programs, regards the challenge as "one of heritage preservation in the context of globalization". Soule says that as the preservation targets not only a scenic attraction but a culture of humanity, a key element to the success of the project is the level of public participation. People have to be clear about who will benefit from the preservation, he says. (

|

| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

|

| Related Stories |

|

|

Product Directory China Search |

Country Search Hot Buys |