In four months or less, a 1,700-year-old village, and the mountain life it preserves, will see water seep through the ancient wood homes, rising higher and higher, until it is completely submerged beneath the jade shoals of the Wu River.

Gongtan of the Youyang Tujia-Miao Autonomous County in southeast Chongqing will unfortunately meet the same fate as countless other unprotected historical sites across China being leveled in the name of innovation.

In its place, the Pengshui Hydro Power Plant will be resurrected, not exactly an attractive replacement for the antiquated beauty of Gongtan, but nonetheless a much-needed jolt for a municipality suffering from regular power outages.

Controversial waterworks are nothing new to Chongqing, the largest inland river port in West China. The Three Gorges Dam project along the Yangtze, one of China's crucial transportation arteries linking the country's interior with coastal provinces, is essential to the region's freight and power industries, but as a result saw numerous small towns and nature reserves sacrificed to the river gods.

Now, one of the Yangtze's chief tributaries, the Wu River, has also been targeted for its hydro-electrical attributes, sparing neither nature nor culture to ensure that all of Chongqing's neon lights continue to glow brightly.

Ironically, Gongtan has never known neon and was only recently introduced to electricity. For centuries accessible only by boat, Gongtan is home to the Tujia people, one of China's more isolated ethnic minorities who hale from the surrounding Wuling Mountains.

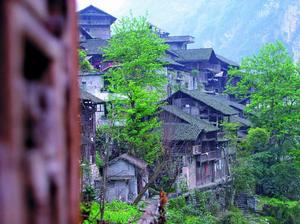

Founded in 200 A.D., the rustic village is a living museum that might seem more destined as a World Heritage Site than a construction site. Designed entirely out of stone and wood in the diaojiaolou-style stilt architecture, the Ming dynasty-era homes are perched against the sloping gorge, facing the sheer, misty palisades which flank the Wu rapids.

Steep, mossy steps lead up from the rocky banks and a single, black flagstone path, polished from centuries of footsteps, traces the 2 kilometer length of the quiet village, a veritable portrait of mountain life as it has been for almost 2,000 years. The slat-wood buildings progress vertically, each offering an increasingly attractive panoramic vista of slate rooftops, the hallmark site of this ancient village.

Unfortunately, the intricately carved work of art that is Gongtan will soon be thrown together in a fateful pyre as the Tujia populous move several kilometers upriver to a white-tiled eyesore already suffering from the noise, pollution and congestion indicative of so many new side-of-the-road Chinese communities.

The land expropriation was in fact opposed by Gongtan residents, who successfully petitioned the central government in Beijing over the property confiscation and were awarded financial compensation for their centuries-old homes. Nonetheless, many Gongtan villagers still refuse to evacuate the aged neighborhood, thus delaying power plant construction until at least the fall of 2007.

This last-ditch effort to damn the dam is of course no match for the bulldozers, but it at least leaves an extended window of opportunity for travelers with an affinity for Chinese history to catch one last glimpse of the real deal before Gongtan is inevitably sent to its watery grave.

Travel Tips

Getting there: From Chongqing, catch a morning coach from the east bus station to Pengshui (six hours, RMB90), then a taxi to the local ferry terminal for an upriver boat to Gongtan (five hours, RMB20).

Where to stay: There are several family-run guesthouses directly overlooking the Wu River with simple, creaky wood rooms wallpapered with old newspaper (¥30 per bed).

(City Weekend by Tom Carter August 2, 2007)