The Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region was a blast of fresh air and I recalled my visit seven years previously when I had trekked along the Great Wall here.

I was excited to retrace my steps, this time with my wife and two boys, and show them what I considered to be one of the finest Great Wall desert landscapes.

The dirt track toward the Wall, from the Gobi Desert plains, was gouged by deep, dried up watercourses, telling of ancient floods that had swept down from the hills.

The jeep coped well with these tough conditions and with little more than an hour's light remaining we reached our camping site.

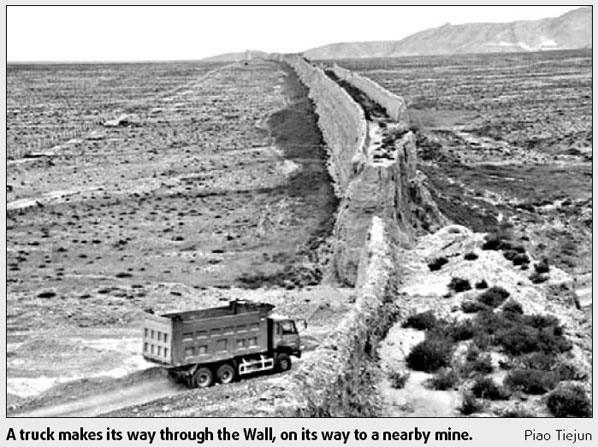

Things had changed a lot. The drone of machinery told of the arrival of mining in the hills nearby. Black smoke rose in the red sky to the west. Power lines poked through a gap in the Wall.

We were tired, had dinner and climbed into our tents. But it was far from serene. We were woken up by occasional blasts and trucks driving through the night.

Next morning we ascended the ramparts. We all agreed that it was higher, wider and better preserved than we imagined it would be.

But for me the view brought sharply into focus why the task of protecting the Wall is so complex.

Firstly, the Wall conflicts with modern life; secondly, it crosses many regional borders.

A mine has been established in the hills, 500 m to the west, which was in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

On the other side of the Wall lay the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, where the authorities in the capital just 40 km away had pioneered protection of this historical landscape by erecting an unobtrusive barbed wire fence.

The mine, primitive and polluting, left a scar on this historical landscape. Another 15-ton truck thundered down the desert road and through the Wall.

I wondered when I would return again and in what way the Wall would be attacked then.

(China Daily December 8, 2007)