Overlooking from some rooms of Yu Wulin's inn, guests can see rolling, mist-shrouded hills and ravines. [Photo by He Shan/China.org.cn]

Overlooking from some rooms of Yu Wulin's inn, guests can see rolling, mist-shrouded hills and ravines. [Photo by He Shan/China.org.cn]

Tucked in a remote hamlet called Laomudeng in southwestern China's Yunnan province, Yu Wulin's guesthouse looks tidy, cozy, and sometimes exotic given its bamboo-made roofs and floors.

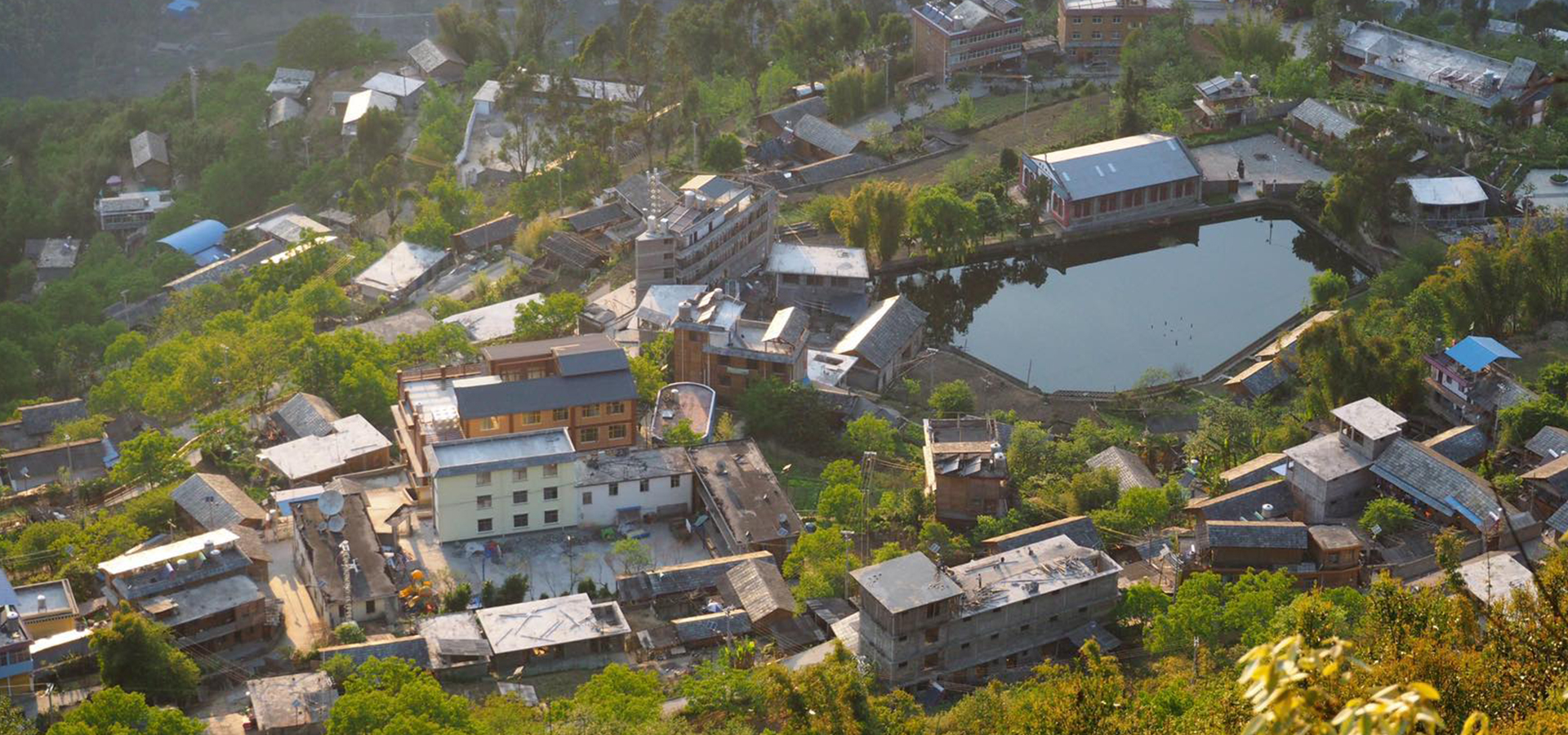

In the Nu dialect, Laomudeng means "the place where people love to go." The hillside village, surrounded by tall mountains and green fields, is best known for its perfect location to take in the view of the Nujiang Grand Canyon.

However, the 43-year-old Yu had not always dreamed of being an innkeeper, and he grew up a farmer like most of his neighbors in the long impoverished region.

Prime real estate

Yu recalls his family to be quite poor when he was a boy. As the fifth and the youngest child in the Nu ethnic family in one of China's poorest areas, he grew up with little food and clothing, and even had no shoes.

What they did have was an extraordinarily picturesque view from their windows: A steep valley and a winding river — the famous Nujiang River. The place remains primitive and intact from the world's hustle and bustle for many years. The only sign of touch by the outside world was a church built by French missionaries more than 100 years ago.

Yu's home sits nearest to the church, and in the 1990s, he began noticing backpackers who trekked muddy roads to reach the remote village. Many asked his family for lodging and dining, and paid cash in gratitude when they left.

Still, Yu had yet to consider it as a money-making opportunity.

"We were just curious and wondered why they had nothing to do but backpacking in such a remote village," he said.

Yu dropped out of high school in 1996 and went to Shanghai as an ethnic singer. That was the first time he went outside of the village. Seeing the metropolis was certainly a novelty to Yu, but homesickness grew day by day until he decided to go back to Laomudeng at the end of 1997.

He married a girl of Dulong ethnicity who he met in Shanghai, a co-worker from the performance troupe. After coming home, they toiled in the farm, but found that they could barely make ends meet.

He said, "Then we lived in a bamboo house. With little financial resources, we could buy new clothes for kids only once a year, and could hardly afford to go to the county's town."

A helping hand

Things began to change in 2000. The local government granted aid to local residents in order to promote tourism. The couple was the first in the village to run a guesthouse.

"The experience of working in Shanghai had broadened my horizon and given me opportunities of making friends," Yu said.

Yu Wulin takes an interview in his guesthouse on April 20, 2019. [Photo by Fang Xiaoqi/China.org.cn]

Yu Wulin takes an interview in his guesthouse on April 20, 2019. [Photo by Fang Xiaoqi/China.org.cn]

Some of those friends helped him manage the digital end of his business. Yu also became fluent in Mandarin, a precious skill in his ethnically diverse hometown where most people communicate in the local dialects.

Meanwhile, Yu's hometown was also getting a helping hand. Yunnan's Nujiang has been one of China's poorest western areas, and the central government has targeted the area for development.

The government helped the local dwellers build houses, pave roads, and gave them access to running water at home.

Yu said, "My success of running guesthouses was largely attributed to the favorable policies and support from the government."

As more and more tourists came to visit the village, he expanded his inn with more rooms in 2012. To help him install expansion, the local tourism bureau granted him 50,000 yuan (US$7,430) of subsidies, and the county government gave him 10 tons of cement.

When his 11-room inn couldn't accommodate more customers, Yu opened his second inn in 2017, with a low-interest bank loan of 2,700,000 yuan.

The inn was built to be more modern, complete with clean toilets, Wi-Fi, and a common area to allow different groups of guests to eat together and sit around an indoor fire pit.

As an enthusiastic music lover, he often shows guests the traditional Nu ethnic dance and instrument, together with local folk performers, bringing them a taste of his culture.

The upgrades allowed Yu to charge a premium rate — 260 yuan a room, compared to 20 yuan a bed at the beginning. His annual income has since risen to 400,000 yuan, a small fortune in the area.

Setting an example

Yu's establishments employ dozens of local villagers, including some of his relatives. He pays them monthly salaries of about 2,000-2,600 yuan.

His success also inspired followers. Eighteen households in the village have since opened guesthouses, and the once shanty-filled village has become all brightly painted houses furnished with sofas and TVs.

"Yu is always ready to help others whenever his peer villagers run into difficulties in operating a guesthouse," said Bian Jianwen, a Fugong county official. "They would also meet from time to time to discuss business and things they could work together on."

Local schools provide free tuition during the 14-year compulsory education scheme. Yu's two sons are majoring in hotel management at a technical secondary school in the capital city of Yunnan. Yu said his own education ended after middle school.

"I hope they will come back after graduation and help to run my guesthouses," he said.

In a remote hillside village of China's Yunnan province, villagers are readying a grand reopening to welcome back tourists this September, following a two-year hiatus. In the village of Pukawang of Dulongjiang township, the key attraction is a number of cottages that double as villager homes and guesthouses.

The village, nestled into the forested hills along the scenic Dulong River, was closed in October 2017 due to renovation work, as part of Dulongjiang's broader plans to improve road access and facilities in the area. The region is home to about 4,000 Derung, one of China's smallest ethic groups.

Resident Pu Xueqing described her old 20-square-meter home, which was made of wood and thatch. In 2015, the government gave her and 12 other households new homes, each worth about 300,000 yuan (about US$44,500).

Each new cottage measures 120 square meters, of which 40 square meters can be used as a guesthouse for tourists. A hotel company manages the villa space and pays yearly rent of at least 5,000 yuan.

"Since the government helped us build new homes that we can partially rent out to the hotel company, our life has become much better," Pu said, adding that this extra income comes in handy: "My family used to depend on corn, potatoes, sheep, and cattle to make a living, and I had to go out of the village to work to support my family."

Tourists flocked to Dulongjiang during the peak season from Spring Festival to the National Day holiday, to take in the unique charms of living besides the Dulong River, which flows south from the Tibetan plateau through this valley into bordering Myanmar.

Kong Yucai, chief of the township, said the upgraded cottages will be able to host tourists who demand more luxury services. In addition to the idyllic landscapes, Kong said visitors will be able to go fishing and take a zip-line across the river.

The entrance to Dulongjiang township. [By He Shan/China.org.cn]

The entrance to Dulongjiang township. [By He Shan/China.org.cn]

At the same time, local authorities are well aware of the need to protect the environment and ensure sustainability.

Gao Derong, who served as the head of Gongshan county between 2001 and 2006, said the Derung people have immense respect for their natural environment.

During the rainy season, when timber washes down from the upper reaches of the Dulong River, villagers fetch the wood from the river to save on the number of trees they need to cut down for firewood.

"We have to keep Dulongjiang as a heaven on earth, and develop tourism while paying attention to environmental protection," Gao said. "That is the largest legacy we can leave to our children."

As a result of these efforts, Dulongjiang, belonging to one of China's poorest regions, was lifted out of poverty in 2018 — an achievement that received praise from President Xi Jinping, who in a letter last month congratulated the Derung people and called on them to continue working for a better life.

"Poverty eradication is only the first step; better days are yet to come," Xi wrote in the letter.

For hundreds of years, the remote area was cut off from the outside world every year from October to April by heavy snow.

In 2014, a 6.68-kilometer-long tunnel opened to traffic, cutting travel time to the seat of Gaoshan prefecture from six hours to just two.

Prior to the road construction, Dulongjiang could be reached only by trekking for two to three days along treacherous mountain trails.

The road-building initiative is part of a larger effort to eradicate absolute poverty in China by 2020, lifting roughly 10 million people from poverty each year.

Aside from infrastructure improvement, the government has also brought aid to residents of the Dulong River Valley in the form of employment and training.

Kong Mingguang has worked as a government-paid forest ranger since 2017, earning 960 yuan a month. He is part of the prefecture's ecological poverty-relief program that employed about 50,000 rangers in 2016. Kong also joined a training program for farmers offered by the local government on planting medicinal herbs and keeping bees.

"Because of my lack of education, I didn't have a decent job and my family struggled to eke out a living," he said. "Since I started work as a ranger, I have regular income and live a better life."

Despite improved conditions, however, the local infrastructure is still far from satisfactory, being one of the few areas in China without a highway, railroad, airport or waterway.

Yin Jianlong, vice principal of a school in Dulongjiang, said education is the key to a better life to beat the odds.

The prefecture provides compulsory schooling for all children up to 14 years of age, including Mandarin classes for children in Dulongjiang as early as kindergarten.

"Here, people over 60 cannot communicate with others in Mandarin, but now young people are able to speak fluent Mandarin, and they are eager to go out to explore the outside world," Yin said.