Lop Nur was once a huge lake surrounded by fertile land in the

northeast of Ruoqiang County in northwest China’s Xinjiang

Uygur Autonomous Region. It found its place in history as a

communication hub of the ancient Silk Road.

By 1972 it was bone dry and had been swallowed up in the “sea of

death” of the Gobi desert. Now there are fears that the tragedy of

Lop Nor might be happening all over again in northwest China. This

time, it is Minqin County that is at risk.

Minqin County is located in the northeast of the Hexi Corridor

on the lower reaches of the Shiyang River. It falls under the

jurisdiction of Wuwei City, Gansu Province. The county is bounded

by the Tengger and Badain Jaran deserts in the east, west and

north. The oasis in Minqin was once a natural barrier in the path

of the encroaching sand. The past two decades have seen it change

into one of the four major sources of sandstorms in north China.

Two factors were involved. There was land reclamation along the

Shiyang River, up-steam from Minqin County and its waters were

diverted for irrigation purposes. Then came years of unprecedented

dry weather. Today the county is one of the driest places

nationwide and it is also one of the most seriously affected by

desertification.

Large-scale exploitation of the groundwater has been lowering

groundwater levels by as much as 0.5-1.0 meters a year in Minqin

County.

As the county has no significant surface water of its own,

the only access to surface water runoff comes by way of the Shiyang

River in the south. With reservoir construction on the upper

reaches of this river now nearly completed, the water reaching

Minqin has been seriously restricted. What was once 30 percent of

the life-giving flow of the river has now dwindled to a trickle of

less than 3 percent. This came against a background of many years

of shrinking surface water resources. The people of Minqin County

first turned to the exploitation of underground water back in the

1960s. Over the years, the main source of water for irrigation in

the county changed from surface runoff to well water, supplemented

by river water.

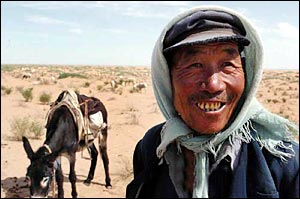

Today in Zhongqu Village of Minqin County, some 400 villagers

live a life of hardship in the midst of the relentless desert.

Village leader, Ma Zhongxing remembers the days of his childhood

when the village was a place of wetlands and reeds. However,

serious drought started to affect the village in 1997. Of the

village’s 15,000 mu (about 1,000 hectares) of land, only 800

mu (53 hectares) are now cultivated. The rest have been

abandoned or claimed by the desert.

"As the water from Shiyang River decreased, we had to dig deep

wells for irrigation. There are five wells in the village going

down 300 meters," said Ma Zhongxing.

According to Chen Dexing, head of Minqin County,

over-exploitation of groundwater in the face of the county’s water

shortage is running at some 428 million cubic meters a year. He

said, "Groundwater consumption is increasing dramatically.

Underground water levels are dropping by some 0.5-1.0 meters per

year. If depletion continues at this rate, the groundwater will run

completely dry in 17 years."

"We have no choice but to draw water from the wells because

there is no water in the river. But using the groundwater has been

turning the soil saline-alkaline," said Shen Jiaodao, a farmer of

Xiarun Village, Donghu Town.

Over-exploitation of groundwater coupled with inadequate

re-supply from surface water, has seen the quality of the

underground water in Minqin deteriorate dramatically. Mineral

content now averages 6g/L and mineralization of 16g/L has been

recorded. This far exceeds the national standard of 1g/L for

drinking water. "Domestic animals can't drink the water, let alone

human beings," said Shen.

About 1.48 million farmers and 180,000 heads of livestock in the

county are facing a drinking water crisis. In some places,

villagers have to fetch water from 10 kilometers away.

Long-term exposure to drinking water with a high fluorine

content has led to a high incidence of malignant tumors among the

villagers with nearly 100 cases a year. In addition, there is a

high death rate among the livestock.

Today the environment and climate make Minqin County a difficult

place to live in. The experts classify the county as having a

severely dry continental climate. Annual precipitation is just 110

mm but evaporation is some 24 times greater at 2,644 mm. It is

commonplace to see newly planted vegetation die off in the grip of

the worsening drought.

The “lake district” of Minqin, comprises five village and towns:

Xiqu, Zhongyu, Donghu, Shoucheng, and Hongshaliang. They are right

in the frontline, facing the advance of the Tengger and Badain

Jaran deserts. In Zhongqu village where Qingtu Lake could once be

found, there are huge clouds of dust in place of an abundance of

water and lush pasture.

All around, the relentless wind is pushing the seemingly endless

deserts onwards towards the oasis threatening to engulf it.

The “lake district” averages an annual 139 days of wind and

dust. Twenty-nine of those days will see the wind pass the force

eight mark, and 37 days will bring sandstorms with winds up to

force eleven. Local farmers often get up in the morning to see

sheep on the roofs of the houses and the courtyard walls

disappeared, buried below the drifting sands. Seventy percent of

the land of the five villages and towns is now lost to the desert

or blighted by saline-alkaline soil. Of the area’s 1.43 million

mu (about 95,300 hectares) only 190,000 mu (12,700

hectares) are still under cultivation. The severe drought has led

to the desert sands encroaching from the east, west and north at an

average rate of 10 meters per year. Some individual dunes are

advancing by up to 20 meters a year.

|

In some places, the arid conditions have become too harsh for

people to make a living. They have been left with no choice but to

move out. Chen Dexing, head of Minqin County, said that in the last

few years more than 30,000 farmers have left their oasis homes to

resettle elsewhere, pushed out by the drifting sands and water

shortages.

The special geographical position and natural environment of

Minqin make its story a classic example of humankind’s struggle to

find water and cope with the desert. With support from governments

at all levels, there have been partial successes in improving the

eco-environment thanks to the efforts of 300,000 local people.

According to statistics from the county's forestry bureau, forestry

plantations had covered 1.4 million mu (about 93,400

hectares) by the end of last year. Desert vegetation had been

established in a bid to stabilize a further 730,000 mu

(48,700 hectares). A 330-kilometer long protective belt of trees

had been completed. This effectively controls the advance of the

sand, while allowing the wind to pass through 188 wind gaps.

"Although some parts of the eco-environment have witnessed an

improvement, the deterioration of the ecology in Minqin as a whole

has not been curbed," said Chen Dexing, "94.5 percent of the area

of the county has now succumbed to desertification. Much of the

desert vegetation has died or withered. Drifting sands extend over

600,000 mu (about 40,000 hectares). There are currently 69

points where sand is impinging along the edge of the oasis and

together with other areas of sand encroachment, these need to be

dealt with urgently.

Minqin’s Hongyashan Reservoir ran completely dry at the end of

June, sounding the alarm bells for the worsening water crisis. It

is the biggest desert reservoir in Asia

As early as the beginning of the 1990s, the provincial

government of Gansu made representations during the initial stages

of planning for the Shiyang River water conservancy project. They

argued that the water flowing to Minqin by way of the river must be

maintained at a level sufficient to guarantee the long-term

survival of the oasis. However the conflicting demands for water in

the upper, middle and lower reaches of Shiyang River have not yet

been satisfactorily resolved.

“Preventing Minqin from suffering the same fate as Lop Nor is a

matter of concern which clearly extends beyond the interests of the

county, city or even the province,” said Chen Dexing. “The root

cause of the widespread deterioration in the local eco-environment

is the widening gap between supply and demand for water. Only by

tapping the waters of the Shiyang River can the oasis be saved from

becoming another dead sea.”

“If this can be done soon it will benefit both the state and the

people, and Minqin can be saved from becoming a second Lop Nur,”

said Chen.

(China.org.cn by Zhang Tingting, September 3, 2004)