Curtain call

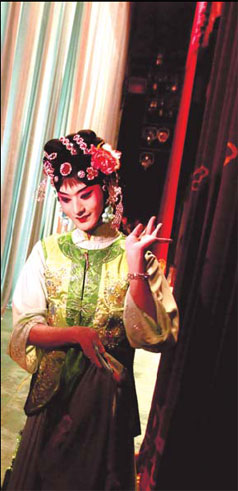

The performer playing the legendary Tang Dynasty (618-907) concubine Yang Yuhuan is a very beautiful woman - for a man, that is.

Hu Wenge, 43, who is showing off his skills at the packed Chang'an Grand Theater, is one of fewer than 10 practitioners of the Peking Opera art form nan dan, in which men play women's roles.

|

|

|

Yin Jun (middle) and Mu Yuandi (right) back stage at the Chang'an Grand Theater during their recent performance. [China Daily] |

Hu is the only nan dan apprentice of 76-year-old Peking Opera master Mei Baojiu and one of the last hopes for the future of the nearly extinct ancient performance style. Mei watches his student's 40-minute appearance from backstage, periodically nodding in approval.

Nan dan branched off near the roots of Peking Opera's evolutionary tree, during a time when women were banned from the stage.

It reached its heyday in the 1920s, with the rise of its four schools. Each of the Four Great Dan was named after the surname of its progenitor - Mei Lanfang, Shang Xiaoyun, Cheng Yanqiu and Xun Huisheng.

But nan dan was labeled as a "remnant of feudalism" in New China's early years, and practitioners were persecuted and even executed during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

The art form re-emerged after the opening-up and reform of the 1980s - but as a shadow of its former self.

"It's on the verge of extinction," says Hu, who studies the Mei school of nan dan.

"But we're still holding on for dear life."

Hu was no stranger to onstage gender bending and was a popular cross-dressing pop singer in the 1980s and 90s. At his career's zenith, he swapped pop for Peking Opera, disappearing into relative obscurity.

"I care more about deserving respect than fame and fortune," he says. "I want to become a real artist."

He completely abandoned the life he'd built, and even left his wife, to study Peking Opera in Beijing in 2000. His passion and persistence moved Mei Baojiu, the son of Mei school founder Mei Lanfang, to take him under his wing.

The following year, Hu, then 34, became Mei's only student and the sole successor of the school.

"Hu was very talented but also cultivated his art through hard work," Mei says.

The middle-aged man faced a steep learning curve and strict instructor.

|

|

|

Yin Jun practices during the break in the performance. |

Although he had studied Qinqiang - a local Shaanxi opera form - as a teenager, grasping Peking Opera proved trickier than he had expected. And Hu believes he was at a great disadvantage starting his training later in life. He had to work three times as hard as younger students, and memorizing the operas devoured his every spare moment.

"It is too bitter for me to think about," he says.

Hu returned to the national spotlight last November, when he performed the Mei school's classic play The Drunken Beauty at the welcoming banquet for United States President Barack Obama's China visit. President Hu Jintao introduced Hu as the third-generation successor of the great master Mei Lanfang.

On March 26, Hu performed with fellow nan dan artists Yang Lei, Mu Yuandi and Yin Jun. Although the three began training as teens, they say starting young also has its downsides.

The Shang school performer Mu Yuandi, 27, says puberty robbed him of his sparkling voice. He appeared as a walk-on performer while training off stage from 1998 until 2002, by which time his vocals were even better than before.

But performance hurdles aren't the only challenges these men face. With most dan plays performed by women, many question the validity of nan dan's existence.

"It's absurd to even talk about nan dan's legitimacy," the Cheng school performer Yang Lei says.

The art form was created by, and performed by, men, and the dan role was designed to suit the male physiology, the 32-year-old explains. Women performers later tried to fit into this mold, but the style hasn't come close to its apex at the time of the Four Great Dan, he adds.

"Male performers have better voices and longer career spans because of their physical advantages," he says.

Mu says actors must be in exceptional shape to stage a three-hour show, especially when the script calls for demanding martial arts stunts.

The Xun school performer Yin Jun points out that men pay greater attention to conveying femininity and consequentially have a more exquisite stage presence.

"Women playing women is life. Men playing women is art," the 22-year-old says.

The performers say stereotypes have surrounded nan dan from its inception.

In patriarchal feudal society, nan dan performers were associated with "homosexuals" and "sissies".

Such pigeonholing has endured through the ages. The blockbuster films Farewell My Concubine and M Butterfly both feature nan dan performers who are effeminate and gay.

Yang calls such typecasting "total nonsense".

He also believes including the word "nan", meaning "male", diverts the focus from art to gender. The performer explains that it was only in recent decades that the word appeared before "dan" to differentiate solely male and co-ed shows.

But living with stereotyping and meager incomes are small prices to pay, the performers say.

"We treasure every opportunity to refine our skills and breath new life into nan dan," Hu says.

"Costumes, makeup, props, lighting - all of these kinds of things can be innovated. But the innate essence of the art form must be preserved."

The bigger question for them is how to preserve that essence after their departures from the stage.

Hu says he hopes he can find a student to become his successor.

|

|

|

Hu Wenge (right) waits for his turn to perform with his teacher Mei Baojiu. |

Yin Jun is the youngest of the four and the only nan dan student at the National Academy of Chinese Theater Arts. He's now preparing for the post-graduate enrolment exam. "I hope fusing theory and practice can save nan dan," he says.

"We face a dilemma in preserving not only nan dan, not only Peking Opera, but also traditional culture as a whole," says Yang Lei, who is trying to revive rarely performed repertoires. "It would be a huge shame if the only place our children could see this is stock footage."

Chang'an Grand Theater manager Zhao Hongtao agrees.

"Younger-generation nan dan performers should be given attention, opportunities and space to develop," he says.

He believes the art form still has a market among Peking Opera fans.

"It has been decades, before the most recent show, since the four schools last shared a stage," Zhao says. "The response was far better than we had expected."

The venue will host another performance in August.

That show will be another flicker of the nan dan's dying flame. But it's also a chance for the art form to catch on and burn bright once more.

0

0

Go to Forum >>0 Comments