Getting to the bottom of Cixi's story

Few women have had as long and uninterrupted sway over Chinese politics and society as Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908). Her story is more fraught and high-octane than the finest Peking Opera, of which she was a connoisseur, and continues to inspire serious research.

|

|

|

Empress Dowager Cixi ruled China for nearly half a century. |

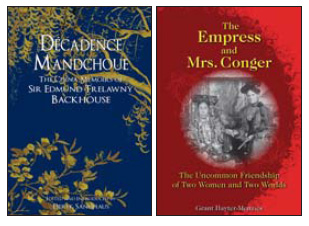

Two new books have added to the ever-growing discourse on the "true story" of the Empress Dowager, whose first biography, by the American artist Katharine Carl, who was also her first portraitist, appeared in 1905.

Both books, in a sense, are an attempt to humanize this imperial ruler who is often seen as a conniving, power-hungry despot. Both try to make sense of the elaborate theater that was Cixi's life. For instance, why did Cixi encourage the Boxers to attack the foreign legations in 1900 and then go on to invite the diplomats' wives - whose lives she had endangered - over to lavish tea ceremonies?

The daughter of a disgraced civil servant, she entered the Forbidden City as a concubine of the lowest rank at 16 and went on to become the undisputed, if de facto, ruler of Asia's largest nation.

In both books, Cixi is treated with informed, if detached, empathy. Except the two books take radically different routes toward brushing the cobwebs off this much-maligned figure. The Empress and Mrs. Conger by Grant Hayter-Menzies (Hong Kong University Press) explores the unusual and sustained friendship between Cixi and Sarah Conger, the wife of American diplomat Edwin Conger, who shared with the empress a love of China's people, art and society and wanted to build bridges across the two cultures.

Decadence Mandchoue by Edmund Backhouse was commissioned and written in 1943 but was not published in the author's lifetime as a large part of it contains tediously-detailed pornographic descriptions of the author's sexual encounters with the empress, besides his intimate free-wheeling conversations with other members of the imperial set-up, like Emperor Guangxu, grand secretary Junglu, the empress's principal eunuch Li Lianying.

Published for the first time by Earnshaw Books in April, with exhaustive annotations and an introduction by Derek Sandhaus, Decadence Mandchoue is a never-before seen, ringside view of Cixi's private and political life, unless, of course, it's a piece of fiction, involving historical figures, written by a man with raging hormones. Backhouse has a history of being the unreliable narrator. China Under the Empress Dowager (1914), which he co-authored with The Times' Shanghai correspondent J.O.P. Bland, was later found to have been largely based on a forged document, the Diary of His Excellency Ching-Shan.

"You can approach this book as complete truth, you can also abstract the idea of a man who loved China and why he did so," Derek Sandhaus, who dug up the manuscript of Decadence Mandchoue from the Bodleian Library at Oxford, says. "Whether he loved Cixi as a person or an embodiment of China is difficult to say."

Similarly, the communion between Cixi and Sarah Conger is difficult to slot. Their bond survived the damages suffered on either side during the Boxer Rebellion, also called the Boxer Uprising. More than 2,000 Boxers died, at least 200 missionaries were killed in Northwest China, the siege of the legation quarters in Beijing alone cost 250 lives. The Forbidden City became a free-for-all territory for rampant looting and arson. Conger was holed up with fellow foreigners inside the British legation for 55 days, surviving on horsemeat and old-fashioned, if self-deluding, faith that this too would pass.

So, when Conger visited Cixi with fellow survivors of the siege, and on subsequent occasions was photographed holding her hand - the only known image of Cixi touching a foreigner - she was, as might be expected, misunderstood, in her own country, in diplomatic circles, and even by her husband.

"In the foreign press of the day, Sarah Conger was blamed for taking a hand 'washed in the blood of Christians'," says Hayter-Menzies, "while Cixi was blamed by the conservative Chinese for befriending a Christian foreigner".

The tie remained strong and steadfast until Cixi's death in 1908, well after Conger went back to the United States and curated an exposition on China at St. Louis in 1904, where Cixi's portrait by Katharine Carl held pride of place.

"Sarah strongly believed the integrity of China's culture and political structure should be preserved from foreign meddling, including that of Christian missionaries," says Hayter-Menzies.

"She also believed the West nursed a skewed image of the East in general and Cixi in particular, and that if people outside China could see the Empress Dowager as she knew her, the caricatures would fade and the truth of both Cixi and China would emerge."

The "truth" about Cixi seems bizarre and fantastical in Decadence Mandchoue. The idea of a young English baronet, polyglot and homosexual - who slept with illustrious writers and artists of the 1890s, including Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley - getting involved with a 69-year-old empress is way too twisted for people with regular tastes.

"To assume sexual encounters are not true because it's too fantastic is dangerous," says Sandhaus. "Backhouse is a Victorian aristocrat who left high society to come and live in Beijing for 50 years. He is weird. And I would think living with absolute power within the precincts of the Forbidden City could produce weird behavior in the bedroom."

There is more explosive stuff. Backhouse suggests Emperor Guangxu was, in fact, poisoned by Cixi. Sandhaus draws attention to forensic tests conducted in 2008 that have revealed heavy traces of arsenic in Guangxu's remains, insinuating Backhouse might not have been too far off the mark. "But it would have been impossible to say it then."

Conger, too, wrote a book on her impressions of Cixi. In Letters from China: With Particular Reference to the Empress Dowager and the Women of China (1909), she wrote about the disarming warmth Cixi showed toward her, about her insatiable curiosity of the world outside China, and also, rather presciently, about "the wonderful awakening" that made the Chinese "reach for something outside of their great nation and their long-time customs and ideas". She saw Cixi as a living embodiment of that reaching out and trying to find China its rightful place in the world.

"She had a powerful curiosity about the way the world worked," Hayter-Menzies says. "She was genuinely interested in the future and China's role in it, especially vis--vis the United States, which she often declared was her favorite foreign country and the one she most wanted to visit."

Cixi's hunger for knowledge and experience is an overriding element in both Decadence Mandchoue and The Empress and Mrs. Conger. Her experiments of the purely physical kind in the former are punctuated by an insatiable curiosity about what Queen Victoria or, a Russian tsarina might do in her situation.

She comes through as a champion of universal sisterhood and women's education in The Empress and Mrs. Conger.

"It was education which had opened doors to Cixi at the imperial court, alongside Emperor Xianfeng and later as regent and administrator," Hayter-Menzies says. "Conger found in Cixi a willingness and interest in furthering education for Chinese girls." After Sarah returned to the United States, her women friends in China sent regular reports of their progress, including news of the school set up by Cixi's adopted daughter, he adds.

Hayter-Menzies does not set much store by the tales of the empress' juicy hook-ups, with Backhouse, or, for that matter, others, like Cixi's favorite eunuch Li Lianying, or grand secretary Junglu, a childhood friend.

0

0

Go to Forum >>0 Comments