|

|

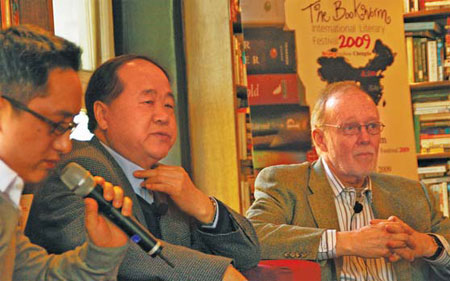

Mo Yan (center) and his translator Howard Goldblatt (right) at the Bookworm Festival. [Photos courtesy of The Bookworm] |

Translators should be a writer's "true soulmate" but when distinguished novelist Mo Yan first met American translator Howard Goldblatt, they didn't click at all.

During Goldblatt's first visit to Mo's home in Shandong province, he felt as if he was being ignored for the first hour. Even food and beer couldn't lighten the awkward situation.

"There was no chemistry at all between us," says Goldblatt. Then Mo lit up a cigarette and Goldblatt, who had not smoked for three years, couldn't resist asking for one.

"We immediately connected - but it took me another three years to quit smoking again," Goldblatt jokes.

In Mo's defense, he recalls his first impression of the professor of East Asian languages and literatures at the University of Notre Dame. Goldblatt wore a suit, glasses, very serious expression and appeared very much as "a man without weakness".

"You often feel awkward when facing someone who seems perfect," Mo says. "But when I found he also smoked, I realized he was human, too."

If the cigarette brought the men closer together, their collaborations since have also helped them understand each other better.

"Autobiographies are not trustworthy," Mo says. "The real story is hidden in novels - you are not only reading the stories but also reading about the writer."

The most careful and serious readers in the world are translators and Goldblatt is "my true soulmate", Mo says. Goldblatt has altogether translated six of Mo's books, more than any other Chinese writer he has worked with.

In Mo's opinion, writers may never find their own mistakes. But translators will. "I am not sure whether he makes new mistakes in his translations - only English readers know that," he jokes.

Mo understands the challenges of translating his books because he is a writer who does not want to repeat himself and tries to achieve variety in his story content, structure and language.

His last book, "Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out," published in 2006, took only 43 days from initial draft to publication. To those who say it can't possibly be a considered work, Mo says that while it was written in 43 days, he had thought about it for 43 years.

"When I was a child, many characters and animals have existed in my life," he says. For example, the character Lan Lian, or "Blue Face", was a man who lived in his wife's village.

When he went to primary school, "Blue Face", who had a big blue birthmark on his face, would push a cart to the school to sell things.

In the People's Commune period where work and life co-existed, and farmers belonged to a collective unit and lived a semi-military life, "Blue Face" did not belong to any unit and fought with everyone.

He paid "a huge price" for is individual behaviors, says Mo, having committed suicide in 1966 during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

"The image of that character always stayed with me," Mo says. "I always thought I would write about it.

"He was considered a bad person but looking back, he had his reasons to be consistent in his principles and I wanted to reflect his individual personality."

The story was originally conceived with a focus on human but later switched to the animals.

"It is because I have deeper compassion with animals than with human beings," he says, relating to his childhood experience. Mo dropped out from primary school and spent a lot of time surrounded by ox and sheep in the following five years. "Many images of my childhood friends have faded but I have never forgotten the animals," he says.

Another character based on a real person is a landlord who did little wrong and was often willing to help the poor. During the "cultural revolution", though, he was killed by mistake. After he died, he was reborn six times as different animals - mule, ox, pig, dog and monkey in 50 years before he was born as a baby with big head and immense language capacity.

Another reason for the speed of the new book was due to Mo's joy at using a pen. He had spent five years using word processors - "the low point of my writing career". He says computers rendered him emotionless and turned his writing into a technical work.

His new novel, "Tan Xiang Xing," is Goldblatt's greatest challenge yet, something both men are agreed on. It is a new experiment in language as it is a dramatized novel or a novelized drama. Divided into three parts - head of phoenix, abdomen of pig and tail of leopard - the story has used a vast amount of lively local folk lyrics consisting of colloquial languages that does not following grammar closely.

"The novel is about sound," he says. "It is the sound from my hometown."

(China Daily, March 18, 2009)