Year-ender: Call it the Year of Weibo

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail

China Daily, December 8, 2011

E-mail

China Daily, December 8, 2011

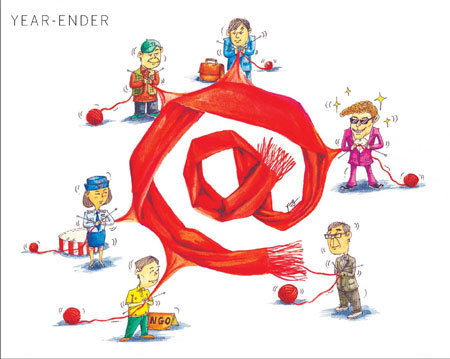

China's army of micro-bloggers weave in their responses to events and people, each contributing a thread to the scarf that encompasses modern society. But not all of them might actually exist.

|

|

Year-ender: Call it the Year of Weibo.[Photo/China Daily] |

"The more the number of people, the stronger we are." Thus said Chairman Mao Zedong in 1949 when China's population was about 540 million. Now, the slogan also applies to the cyberspace, China's online population being more than 500 million. And micro-blogging, with an impressive growth rate in 2011, has become one of the most important tools for the Chinese to leverage the wisdom of the crowds.

2010 was dubbed as the "inaugural year" of micro blog, or weibo in Chinese, in China. 2011 is marked by its unstoppable growth. The number of micro-bloggers has grown from 63.11 million by the end of 2010 to 300 million in 2011.

For many individual users, spending time on micro blogs has become a daily necessity. It is their way of interacting with friends, following their favorite celebrities, sharing the pictures of cute pets, reading and commenting on news updates.

Just as "tweet" has become a verb in English, "zhi weibo" - literally "weave a scarf" - has entered the lexicon in China. Weibo means micro blog but sounds like scarf in Mandarin.

More importantly, intense participation by a humongous number of people often adds real value to the seemingly-inconsequential 140-character messages, throwing light on different aspects of society.

Traditional media and reporters are facing more challenges as well as opportunities. NGOs are learning to use micro blogs to promote charity and raise social awareness. Businesses and celebrities use it to promote their brands and personal images and interact with their fans and consumers. Government officials are beginning to use new media for a variety of tasks - from accessing public feedback to coming up with fast responses to sudden developments.

Making news together

Among the many jokes circulating across micro blog sites, one goes like this: When one's weibo fans exceed 100,000, the influence is equal to that of a big city daily; if the number reaches 1 million, it is comparable to a national newspaper; once the number goes beyond 10 million, it's the equivalent of a TV station; and if the number of fans soars to 100 million, it is equal to the reach of China Central Television station.

It aptly shows how the rise of social media is changing traditional media and journalism in China. Statistics released by Chinese Academy of Social Sciences show that 70 percent of weibo users consider it the most important platform to get news.

And, more importantly, news in the age of social media is no longer gathered exclusively by reporters, but emerges from an ecosystem of short texts where reporters, sources, audiences exchange information to piece the whole picture together.

"Many people may not notice the fact that they are already amateur reporters when they are sending or forwarding messages on weibo about a certain piece of news," said Zhou Qingshan, deputy dean of the information management department at Peking University.

On July 23, a high-speed train rammed into a stalled train near the city of Wenzhou in the eastern province of Zhejiang, leaving 40 dead and 191 injured. The first report about the crash appeared on weibo, more than two hours earlier than the media reports on the Internet, Xinhua News Agency was quoted as saying.

Up to the noon of July 24, 16 hours after the crash, 3,286,883 messages were sent on Sina micro blog by eyewitnesses and people who were near the crash site. They used words, photos, and videos to keep the netizens updated about the rescue work.

During the past 11 months, almost all the disaster reports were first released on weibo, such as traffic accidents, earthquake and mudslide; vindicating the tremendous reach of weibo in the first place.

"Usually, newspaper or TV station reporters, due to limited resources, cannot always reach the spot or connect with the concerned people immediately after the news happens. But for social media, it's totally different." Zhou said, "Weibo users, just like news reporters, stop by when they see something newsworthy happening. They can send the message immediately and keep updating the process."

"Although weibo has many obvious advantages compared to the media, it cannot satisfy people's demands for in-depth analysis of new events, because of the 140-character limit," he said.

Reporters, meanwhile, are more inclined to use social media websites as a valuable adjunct to their reporting and sources of news leads.

"The popularity of weibo has greatly changed people's view of news and is a big challenge to the media. Media needs to change to tackle the challenge," Zhou said. "A short message can lead to a public event, everybody is a reporter."

But experts say unlike traditional media, the release of each piece of news is filtered by several people. Before publishing a particular news sourced from micro blogs, reporters, editors and the media need to check the facts. Rumors can spread more easily through micro blogs.

Gov't agencies sign up

By the beginning of 2011, the opening of "official micro blogs" was already a noticeable and growing trend in China. A report issued in April this year by the People's Daily Online Public Opinion Monitoring Center noted that "micro blogs for Party and government institutions and officials already cover many administrative levels, from central to local, and many functional departments."

It estimated that more than 2,000 micro blog accounts had been set up by government departments at Sina's weibo.com. Sina is one of China's biggest micro-blogging service providers.

While some departments have used weibo to communicate with the public in a more proactive way, many others stuck to just releasing information.

Earlier this year, public security departments opened several accounts. Now other departments are catching up as well. Last month, Beijing municipal government launched an official micro blog, covering 21 city departments.

Yu Guoming, journalism professor at Renmin University of China, suggested governments use their accounts more to respond to people's problems, and less to deny rumors. "After two years, weibo users can tell false claims. People are in favor of weibo for it is a channel for them to express their wishes and report the problems they have met with."

Close watch on charities

In June, a 20-year-old woman named Guo Meimei claimed to be the general manager of "Red Cross Commerce" - an organization that the Red Cross Society of China says does not exist, and was pictured posing in her sedan Maserati and flaunting her wealth on her micro blog.

The behavior provoked a public outcry over whether the charity had misused donations. Donations to the Red Cross Society dropped immediately after the incident. It also dented China's fledgling charity sector.

"This year, China's charity programs were faced with a severe credibility crisis, with weibo drawing huge public attention," said Deng Guosheng, professor of school of public policy and management, at Tsinghua University.

Deng explained that in the past Chinese people did not know of an effective way to register their complaints against semi-governmental charity organizations. Now micro blogs have given them a channel to express their distrust.

This year some of the new grassroots charities were started in the form of short texts by leading figures in the weibo world.

Nearly 10,000 children living in underdeveloped rural China will no longer study on an empty stomach, thanks to one man's micro-blogging, which spiraled into a nationwide charity program in just a few days.

Deng Fei, an investigative reporter since the last 10 years, has about 760,000 followers on Sina micro blog. Staring April, he launched a program called Free Lunch, aiming to provide children in rural areas with a free lunchbox containing an egg, a vegetable and some rice. The program calls the public to donate 3 yuan, or 40 US cents, each day to provide one basic but nutritious school lunch.

Late in March, the program's creator, Deng Fei, posted a message on Sina micro blog, saying he was going to help build a canteen at a primary school in Southwest China's Guizhou province. The post was immediately circulated by his followers and received widespread public support across the country. Thanks to the tremendous reach of the micro blog, the Free Lunch Fund has, so far, supported more than 40 schools and over 20,000 students.

It became the first grassroots charitable program initiated by 500 journalists that eventually led to a policy decision by the government to support children from poor backgrounds by offering free food, a joint effort with China Social Welfare Education Foundation.

Making up the numbers

In November, Sina micro blog announced the number of their micro blog subscribers had reached 250 million. Over 75 million messages are forwarded or circulated daily.

It has become a recent trend to promote celebrity and brand marketing on micro blogs.

Yao Chen, an actress, has been crowned China's "Queen of micro blogs" with more than 15 million followers. But with the emergence of "zombie fans" it is now easy, even cheap, to surpass her, one of the most followed celebrities in the world, in terms of fan following. At the current price of four yuan per thousand fans, anyone can beat Yao by shelling out 60,000 yuan.

The emergence of "zombie fans" has become a recent trend to promote celebrity and brand marketing. Such fans are often created to generate hype for promoting a certain product or person.

Comments are on sale as well. Many public relation companies are savvy at hiring "water army" to criticize or praise a certain public figure or products.

Xiao Mingchao, a researcher studying weibo marketing for Sinomonitor International, a Beijing-based new media analysis organization, said: "Faked prosperity is destroying the credibility of businesses. This leaves little room for companies that would like an accurate evaluation of the brand. This undermines the value of micro blog assessments in the marketing process."

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)