Remembering Sidney Shapiro: Famed US-born Chinese translator

- By Huang Youyi

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, October 29, 2014

E-mail China.org.cn, October 29, 2014

Editor's note: Sidney Shapiro, a famous U.S.-born Chinese translator and author (whose translations includes the landmark "The Outlaws of the Marsh") and one of the very few Westerners to gain Chinese citizenship and become a high-ranking member of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, passed away on Oct. 18 at the age of 98. His long-time friend Huang Youyi, former vice president of the China International Publishing Group and vice director of the Translation Association of China, wrote an article, "The Forever Young Sidney Shapiro," to commemorate Shapiro's life and work. China.org.cn has translated the article and reproduced it here.

|

|

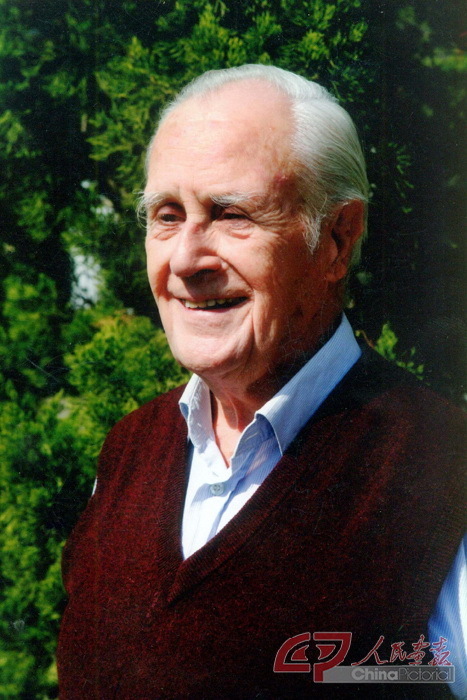

Sidney Shapiro, a famous U.S.-born Chinese translator and author.[File photo] |

On the morning of Oct. 18, just two months short of his 99th birthday, Sidney Shapiro passed away peacefully at his home. Upon hearing this news, I called off the preparations that I and several friends were making to celebrate his 100th birthday and recalled the old bygone days.

I first came to know Lao Sha (Sidney) personally in 1977. Though the notorious Gang of Four had been brought down, the May Seventh Cadre Schools (re-education programs for intellectuals that combined agricultural work with the study of Chairman Mao Zedong's writings) were still in operation. We first met in Gu'an County, Hebei Province, where a number of experts and scholars specializing in international communication at the China International Publishing Group were working; Sidney was the only expatriate there. We often got together to listen to foreign broadcasts, discuss international news stories, debate how China should carry out international communication and of course, translate Chinese books into foreign languages.

I had just returned to China after studying in the U.K. at that time. What with my enthusiasm for spreading Chinese culture and my close acquaintance with Sidney and the other experts, I was rather free and open about my thoughts. One day, I said that we should not content ourselves with only translating Chinese books, but we should try to write in English. My Chinese colleagues did not raise their eyebrows at this to help me save face, but Sidney said to me in a serious yet amicable tone, "Young man, don't think too highly of yourself. You do not know the true essence of international communication yet. You should hone your translation skills first, as writing directly in English is far more difficult. Whether and when you write in English will depend on the progress you can make in the future." His words cooled my fervor, and I then began my career in translation and publication with this in mind.

My friendship with Sidney developed in the 1990s when I published his book on Shafick George Hatem (a U.S. doctor who spent decades practicing medicine in China). I then found out that he only took up writing about Chinese culture after successfully translating a dozen books. What he penned ranged from biographies to economic reform tracts, from criminal law texts from ancient China to documents relating to Jewish immigrants in China (Sidney was of Jewish ethnicity). I saw what the Chinese idiom "Zhu Zuo Deng Shen" literally meant when I visited his house – the stack of his publications far exceeded his bookshelf in height. More extraordinarily, each of his publications has been published in many countries, thanks to his remarkable experience and his international reputation. He is, in today's words, one of the earliest Chinese writers who reached beyond the border.

As a seasoned translator, Sidney still carried on with translation projects. I remember a period when he often phoned me or invited me to his home to explain some phrases and incidents from the Cultural Revolution for him. I thought that he might be working on things that had to do with that time. Later he told me he was translating "Deng Xiaoping and the Cultural Revolution: A Daughter Recalls the Critical Years," a book written by Deng Rong, Deng Xiaoping's daughter. The English version of the book was published in 2003. It was the last book Sidney ever translated.

Sidney was steeped in both Chinese and American culture. He was a great fan of Western classical music, and he was also the first among my senior colleagues to use the Internet. Even in his 70s, he still liked to ride his motorcycle around Beijing looking for Western cuisine.

I recall one day in the 1980s when I brought some articles to his home for editing. He was wearing glasses and trying to solder the electric wires on his radio. "Good thing you're here. My sight is failing, can you please help me with this?" he said. I had never done that before, but I could not refuse to lend a hand. Eventually I managed to solder the wires, but I burned the plastic back of the radio. Radios at that time cost a fortune, so I dared not tell him. He never mentioned this afterwards, and I never know whether he did not notice or if he just cut me some slack.

I used to tell others U.S.-style jokes making fun of current affairs. I was often asked where the jokes came from, and now I can reveal that they were mainly from the emails that Sidney sent me over the years.

A person's vitality is demonstrated in many aspects: interest in good food may pass as one of these. As Sidney grew older, my colleagues and I decided that his birthday should be celebrated in a cozy rather than a lavish manner. Every year around December, we would ask him where and what he would like to have for his birthday dinner. He often made the choice very quickly, sometimes picking a Western restaurant that he saw recommended in newspapers. When it came to the dinner, there was always laughter and joy.

As time went on, occasions like this became fewer and fewer. But the numerous masterpieces on his bookshelves and his amicable countenance and hearty laughter are still etched in my mind. For years we greeted each other as "young man" when we met. Sidney is still young in my mind!

The article is originally written in Chinese and was translated by Zhang Lulu.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)