US Sinologist reveals links between Confucian culture and founding of US

- By Vasilis Trigkas

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, July 21, 2016

E-mail China.org.cn, July 21, 2016

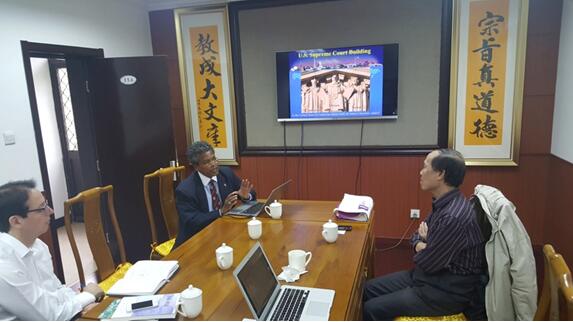

Professor Wang Xiaochao, director of the Center for the Study of Greco-Roman Philosophy and Religion, recently hosted Professor Patrick Mendis, a Rajawali senior fellow at Harvard Kennedy School, at a forum in Tsinghua University to discuss his pioneering research on the Chinese culture and American civilization.

An educator, diplomat, and member of the U.S. State Department's National Commission for UNESCO, the Harvard scholar shared his research and insight regarding the intellectual traditions and architectural symbols of the Confucian and Greco-Roman heritage that inspired America's founding fathers in their atypical pursuit to establish a flourishing new republic across the Atlantic Ocean.

The influence of the great classical scholars of Greece and Rome is easily discovered in the Greco-Roman facades and architectural design of Washington, D.C., and its Federal Buildings and the surrounding sculptures. But the most popular writings of the founding fathers demand a more concerted scholarly effort to locate and identify the Confucian inspiration in America's founding. In his scholarly research, Professor Mendis focused on primary sources and historical references, both in the U.S. and Europe, to illustrate China's contribution to the early American republic.

The American founding fathers, especially Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, discovered the Chinese classical heritage through their interactions with Europe, Professor Mendis explained. The works of famous Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci (1552-1620) and his missionary colleagues led to the seminal book, "The General History of China," edited by another Jesuit priest Jean-Baptiste Du Halde in Paris. The text—an encyclopedic survey of Chinese people, their history and Confucian culture—had a remarkable influence on colonial America, especially among the intellectual circles. Not only did the European philosophers of the Enlightenment draw on the book, but it also decorated the libraries of Franklin, Jefferson, and others.

In the Philosophical Dictionary, Voltaire declared that China "had invented nearly all the arts almost before we were in possession of any of them . . . in our pretended universal histories." The American founding fathers meticulously studied Chinese culture and literature; some of America's most eminent polymaths visited Paris and dialogued passionately with the French philosophers.

Professor Mendis explained that Dr. Franklin in particular foresaw the power of virtuous and moral leadership expounded in the Chinese Classics as a complimentary and necessary ingredient for republican governance.

"When he [Confucius] saw his country [China] sunk in vice, and wickedness of all kinds triumphant, he applied himself first to the grandees; and having by his doctrine won them to the cause of virtue, the commons followed in multitudes. The model has a wonderful influence on mankind." –from Dr. Franklin's letter to Reverend George Whitefield on July 6, 1749

Similarly positive reflections on China were expressed by Charles Thomson, the secretary of the Continental Congress; Thomas Pain, whose powerful pen contributed pivotally to the outbreak of the American Revolution, the Harvard scholar pointed out.

The admiration for the classics of China and the Chinese culture is not limited to scholarly and popular statements, but is also reflected in the architectural elements of the nation's capital in Washington, D.C. The Confucius statue decorates the eastern pediment of the U.S. Supreme Court Building along with Moses and Solon. This signifies the importance of Hellenic, Judaic, and Confucian traditions that provides the most comprehensive and complete set of commonalities shared in the American republic to govern human behavior and social order.

In his view, Professor Mendis maintains that the strongest bond between the American founding fathers and the cultural traditions of China was the Deist nature of their shared cosmology. For the founding generation, Nature's God or Providence was used to build a laic polity (in the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution), which is similar to the Confucian and Daoist traditions of All Under Heaven or the Mandate of Heaven—the phrases associated with the Jesuit writers and missionaries.

For the American founding fathers, the spiritual elements of their cosmology were reflected into a most creative and passionate engagement with Freemasonry as well as the general architectural macro-design of the new Federal City in Washington, D.C. Both Washington and Beijing were built to reflect certain celestial alignments with stars and geometrical orientation; the former was designed to obey the inalienable laws of Nature's God, the latter is to safeguard the Mandate of Heaven.

Professor Mendis concluded his lecture with a question,"Will there eventually be a shared heritage in the future of Sino-American relationship? "

There is no mistake that the current status of the Sino-U.S. engagement is "commerce driven." Trade, investment, and market have been the dominant factors that bring the two largest economies and peoples of the Pacific Ocean together. In his latest books, "Commercial Providence" and "Peaceful War," Professor Mendis addressed this dimension of Sino-American commercial intercourse.

Yet, a closer inquiry to the very roots of the American and the Chinese forma mentis reveals the potential for a more direct engagement between the two—an engagement based on core philosophical and cosmological principles that the founding generations of these two civilizations had understood yet their successors have neglected.

Those symbols and principles in architectural designs are in front of our eyes, the Harvard scholar summarized; however, the hidden meanings of these seemingly decorative motifs—whether they are in the Federal Buildings of Washington or the Temples of Heaven, Sun, Moon, and the Forbidden City of Beijing—are understood by few.

Vasilis Trigkas is an Onassis Scholar and Research Fellow with the Center for the Study of Greco-Roman Philosophy & Religion at Tsinghua University.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)