Editor's notes:

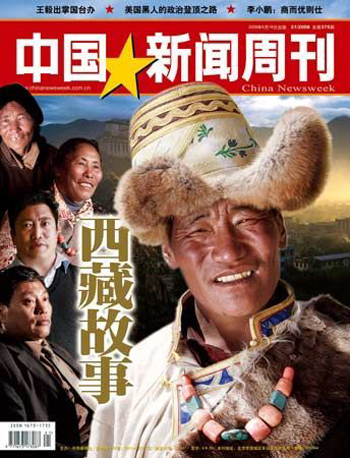

Tibet, for many of us, seems so far away. Tibetans are so mysterious. We should learn more about this land; even some Chinese scholars have admitted ignorance about Tibet. The China Newsweek magazine recently published a story about the struggles and progress of an ordinary Tibetan family over the last 60 years. We translated it and hope it can help you get a better understanding of Tibet.

Ngari, an administrative area in the western part of Tibet Autonomous Region rests about 4,500 meters above sea level. As in many other parts of China, the area, although harsh, has been undergoing a historical transformation.

Tsering Gyalpo, now director of the Institute of Religious Studies, Tibet Academy of Social Sciences (TASS), was born in the pastureland of Ngari in 1961. The road that his family has traveled on from 1959 to the present day particularly reflects the changes in Ngari and in Tibet as a whole.

Tsering Gyalpo's parents, Jampa and his wife Lhamo Tsering, are traditional herdsmen. They have five boys and three girls. Like their ancestors, they lived an isolated life before 1959. They did not own any land and Jampa had to work extremely hard to support his family.

In 1959, Lhasa saw bloody riots initiated by Dalai Lama's followers, causing the Dalai Lama to flee and the People's Liberation Army entered the region.

When the PLA came to Ngari, terrible rumors arose that the Han people would confiscate private property belonging to the rich and that all the wealthy men would be eliminated. Consequently, most rich locals fled to India. In Jampa's village, only about 30 households out of more than 50 remained.

Like his fellow villagers, Jampa feared the Han army quartered in his neighborhood. At the begin all the villagers did not dare to get close to them at all. Once, in order to get a temporary job, Jampa had no choice but to go to the Han community. When he came back, he told his family and friends that Hans could reason and they were nice people. From then on, this Tibetan's impression of Hans became favorable.

Most importantly, Jampa and his family began to embrace a new era. His children would get many unprecedented opportunities for making a good life. One of his sons would become a well-known scholar; another son a successful businessman; one of his daughters a senior governmental official.

Ngari during the 'Cultural Revolution' period (1966-1976)

Before 1966, Tsering Gyalpo's family owned their flocks and herds, but under "mutual aid teams" formed to group the local people to work together. This was the prelude of the "People's Commune System".

Some cadres of both the Han and Tibetan ethnic groups came to this pasturing areas in the capacity of "a work team" designed to "help" the herdsmen learn more about the outside world and Communist policies. Cadres also bought flocks and herds from richer families and then allotted them to the poorer.

Tsering Gyalpo and his foreign students. (File photo) |

Tsering Gyalpo was helping his family feed the sheep at that time. His eldest sister, 18-year-old illiterate Dorji Drolma, became the accountant of the local production team. The young accountant knew nothing about arithmetic and had to keep accounts using pebbles. Tsering Gyalpo's eldest brother was sent to the city in the worker enrollment plan in 1965 and became the first member of the family who walked out of the pasturing area.

From 1959 to the time nearly before the Cultural Revolution, Tsering Gyalpo spent his days tending sheep and learning Tibetan language from his second elder sister. "I scratched on the sands in the summer and on snowy ground in the winter. My fingers even became bruised," he recalled.

Time passed by peacefully during his finger-writing days. But one day he found his self-study materials had been secretly taken away by his father and subsequently lost.

Tsering Gyalpo told the China Newsweek, "It was something like a Buddhist scripture collection and included our local and family histories."

Later on, Tsering Gyalpo understood that the Cultural Revolution had arrived.

At that time he perceived the Cultural Revolution as meaning that some of his richer uncles received criticism and were denounced at the public meetings. He said, "Even the little children could kick and abuse him, I felt very sorry for that."

Things like what happened to his uncle could occasionally be seen in the political study meetings. Once Tsering Gyalpo's sister told her family, "Our uncle's teeth were knocked out and his hair was ripped off his head."

During this period of time, Tsering Gyalpo's eldest sister Dorji Drolma organized local herdsmen to learn about the policy papers and told them that exploitation and oppression from monks and landlords made them hungry and poor.

On April 25, 2008, over 60-year-old Dorji Drolma recalled the past, saying, "I myself also used to criticize and denounce the landlords. The young and the poor all supported this kind of action."

In 1969, the pasturing area where Tsering Gyalpo's family lived for generations changed its name to "Red Flag Commune" and all of their flocks and herds were collectively owned.

Tsering Gyalpo's family was assigned to feed over 600 sheep, but they couldn't eat or kill any animals. If the sheep were raised properly, each family member would receive 10 points per day. At the end of a year, the commune would allot meat, dairy food and butter to them according to the points they had accrued. Under this system the local people were still not rich but they did not starve.

Tsering Gyalpo was less than 10 years old then and he knew nothing about what and why things happened. He kept on living his own life, stealthily taking out the volumes of sutras handed down from ancestors and reading them while feeding sheep. In fact, the kind of scrolls he read were criticized and forbidden at that time.

He had to hide his reading materials in the legally published Tibetan calendar during the day and in a cave at night. Because of his reading habit, his father was so angry that he beat Tsering Gyalpo, yelling: "Could this scroll feed you? You'll never become a monk, why do you read them all the day?"

In the past, people in Tibet who read scrolls aimed to become a monk, so that they could be provided with adequate food and clothing, and be respected.

However, the Cultural Revolution changed all this. Tsering Gyalpo remembered that so far his village Langjiu had only one person who become a monk but later returned to secular life. Tsering Gyalpo mused, "The Cultural Revolution is one reason, and another is that the opening up policy has also made young people not yearn towards religious life."

During the most heated period of the Cultural Revolution, people in Ngari were busy breaking the "Four Olds" (old ideas, old culture, old customs and old habits) just like what people did in the other parts of the country. The "Red Guards" took the lead in smashing and dismantling temples, leaving the Buddhist statues destroyed and sacrificial jewels falling everywhere.