By WANG Ke

China.org.cn staff reporter

Read more stories on China's Reform and Opening up

One night in December 1978, Guan Youjiang and 17 other farmers from Xiaogang Village broke the law by signing a secret agreement to divide the land of the local People's Commune into family plots. They agreed to continue to deliver existing quotas of grain to the government and the commune, and keep any surplus for themselves.

This was the beginning of the story of Xiaogang Village in east China's Anhui Province.

A model for China's early reform

At the time, Xiaogang was notorious locally as a place where people would sell off their possessions to buy food and other necessities, and had to borrow money to buy seed for planting. Residents tended collectively owned fields in exchange for "work points" that could be redeemed for food. But the commune was never able to grow enough. In the bad years, people starved. 1978 was a very bad year.

Guan told China.org.cn that some families were so hungry they boiled poplar leaves and ate them with salt. Others ground roasted tree bark into powder to use as flour.

|

|

The restored 1978's thatched-roof flat. (China.org.cn / WANG Ke)

|

"I used to roam the countryside begging," said Guan, a tanned man who left school at the age of 12. "Everybody was dying of hunger. The village population was only 120 before 1958 and 67 villagers died of hunger between 1958 and 1960. In Fengyang County (where Xiaogang is located), a quarter of the population died – 90,000 in all."

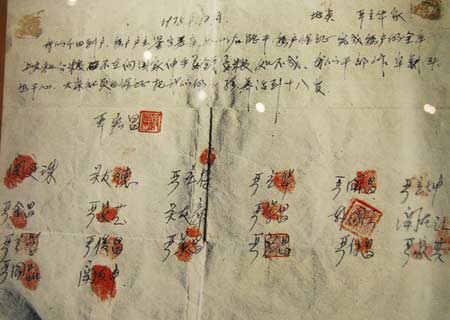

On the night of December 1978, all 18 of Xiaogang's households met after dark in the biggest house in the village. After a short discussion, they signed or put their thumbprints on a 79-character document agreeing to divide the commune's land into family plots.

|

|

The secret agreement in 1978. (China.org.cn / WANG Ke)

|

One of the signatories, Mr. Yan Lihua, now 64, told China.org.cn: "The decision was made out of desperation. We divided up the land to save our lives. If we hadn't, we would have died of hunger."

"In the case of failure, our leaders were prepared to face death or prison, and other commune members vowed to raise our children until they were 18 years old," he said.