|

|

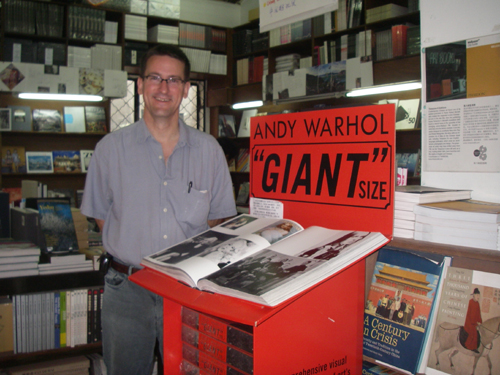

Valerie Sartor / China.org.cn

Robert Bernell

|

By Valerie Sartor

China.org.cn columnist

American born Robert Bernell has created a niche that no one else, foreign or Chinese, has been able to copy or surpass.

Bilingual, business savvy and full of passionate enthusiasm for contemporary Chinese art, this astute and attractive businessman has many fingers in the pie: He's started a unique publishing business with his own imprint: Timezone8, two contemporary art bookstores of the same name (Beijing & Shanghai) and also he has established himself as one of the world's experts on contemporary Chinese art.

"All of it was accidental but I'm really glad it turned out this way," he said. "These artists are my friends and I think that their work is dynamic and incredibly interesting."

Mr. Bernell will never get super rich cashing in on his knowledge or his friendships but he doesn't seem to mind. "I'd guess that my art book business has reached a plateau. There's a lot of small stores opening up, competing with us, but the twoTimezone8 stores are the largest contemporary Chinese art and culture book stores around," he said, sitting comfortably in his café attached to his Beijing bookstore. Smiling, relaxed and spiffy in blue jeans and a starched blue shirt, this accidental 40-something entrepreneur enthusiastically talked about his life in China and how he became intimately connected to the 798 contemporary art scene.

"In 1997 I started up Chinese-art.com; it is art news and was considered to be one of the five best websites in the world by 2001. We were putting out 500-1000 images a month and 20-30 art articles every two months. We also did a bi-monthly guest edited newsletter – it was written by critics and writers here in China. We gave them complete freedom," he said, pausing to swig some sparkling water. "But I'm not an artist. I started out as a computer programmer and a translator. At Stanford I studied Chinese language and literature and then I went to Nanjing University, where I met my future wife, in the late 80's. In Nanjing we went to art galleries and openings and artists' homes so there I began studying Chinese art."

Robert Bernell recounted that he felt thrilled to be in China and fascinated by Chinese art, especially contemporary Chinese art. He had built a highly regarded art website – the only problem was that he wasn't making money. In 1999 he took the content down and sent it to John Clark, a preeminent scholar of art history at the University of Sydney. A book was born and it sold "really, really well" according to Bernell.

This led him to write another in 2001, again using his web content. He gave the information to a University of Chicago art authority and the book: Chinese Art at the Crossroads, sold out immediately. "We figured this was a winning model so we started to publish more and more art books," Bernell said, grinning hugely. "I was working at that time out of Lucky Tower on the Third Ring Road. It was a small office with dismal gray carpet, cheap gypsum walls, very bleak, very drab. We needed space but we had little money so I started to explore factory spaces around Beijing."

Bernell explained that in 2000 the Beijing municipal authorities were relocating factories outside the city perimeters, so many industrial areas were being vacated. "Factories have electricity and water and lots of space, and they are on bus and transportation routes: plus they're cheap, or were at that time."

|

|

Valerie Sartor / China.org.cn

Robert Bernell

|

He looked at 20 factories. "I settled on this place at 798. It used to be a Muslim canteen where they made steamed buns and halvah. The walls were caked with grease, there was a hole in the ceiling where the exhaust pipe had vented out, but it was cheap: only 6 jiao per square meter or 2000 yuan per month. That was less than I paid at Lucky Tower at the time."

He cleaned up the space and started using it as a base to translate, write and publish art books. "At that time only 20 percent of the factory spaces were occupied," Bernell said. "A now famous sculptor used a space at 798 for large scale projects, but when Cang Xin, China's top performance artist, moved in everything changed."

Cang Xin's wife, Xiao Li, was very good at negotiating property leases for other artists. "At that time, remember, artists were not popular; they were stigmatized and considered as freaks. Xiao Li helped them, these 'orphans', to find a home. She acted as a property agent and never charged any of them."

As the artists started to work at 798 they also started to congregate at the Timezone8's coffee shop. "Artists told me that they needed foreign art books, so I started importing them and they sold well." Bernell was sensitive to what the artists were keen on and sensitive to what was imported; he never had any censor problems. "I had a gentleman's agreement with the government: I avoided bringing in anything that would upset the authorities: nothing pornographic and nothing political," Bernell said, adding: "Mao said that the body and nudity were essential for the study of art, but he did not say anything about sex or porn."

Bernell was publishing more books using his imprint via Hong Kong and found himself strongly influenced by Hou Hanru, one of the most important thinkers in Chinese contemporary art. In the late 90's there was a strong rationalist movement toward anti-foreign creations along with a desire to make everything "look Chinese" – such as putting a pagoda on a high-rise building. Bernell commented, "Hou Hanru said that this kind of action was disingenuous and misleading. It just continued a stereotype. I was greatly influenced by this man; he helped to define Chinese art as it is today and so does Timezone8."

The Chinese contemporary art movement is the most dynamic art movement in recent history according to many world experts. Bernell remarked that there is still quite a lot of room for publishing art books in Chinese. "The growth of contemporary art books in English is slow and steady, but the overseas market is growing," he said. "What's happening in contemporary Chinese art has definitely eclipsed what happened in traditional Chinese art due to the dynamics behind today's culture. China is taking her rightful position in global cultural discourse."

Bernell explained that 798 developed along a similar trajectory as Soho or Greenwich Village in New York: "Artists moved in when the rent was cheap and the large, interesting spaces lured them. Like artists in other districts they fed off each other. Getting together on a regular basis, doing events and shows, they became stronger as individuals. This fed the growth on 798. It became a center for writers, movie producers, everyone from the art and culture world."

In the last several years many artists have moved away from 798. They still congregate to meet and have shows but the higher rents and the fact that too many people try to access them while they're working has caused an exodus. "But a significant part of the creation of art happens in the discussions, the interactions, the viewings of art openings – that's where ideas are germinated, even refined," Bernell said. "The execution done in a studio in many ways may not be as important as the other things I just mentioned."

Clearly Robert Bernell loves his trade and has deep affection for his artist friends. His newest book on 798 – Beijing 798: Changing Art Architecture Society in China – will come out soon. "I didn't plan any of this to happen," he said wryly. "I had dreams of doing tri-lateral trade and making millions. But after I started getting interested in art, in Nanjing, with my future wife, that dream started to fade. Today I enjoy my life and I live it one day at a time. Every day in China's art world is well worth watching and living through."

This website lists Mr. Bernell's books: http://www.chinese-art.com/Contemporary/indexv5i2.htm

(China.org.cn July 22, 2008)