French philosopher and writer Denis Diderot (1713-1784) proposed the term "fourth wall" in theater and it spread with the advent of theatrical realism.

The fourth wall is the imaginary wall at the front of a three-walled stage, through which the audience sees the action in a play. Even though it is not there, physically, the audience is supposed to assume there is a "fourth wall" present.

The term has been adapted to refer to the boundary between the performance and the audience. American film critic Vincent Canby (1924-2000) described it in 1987 as "that invisible screen that forever separates the audience from the stage".

There has been a trend to "break" the fourth wall by having a character directly address the audience, for instance, or having characters interact with objects outside the context of the work.

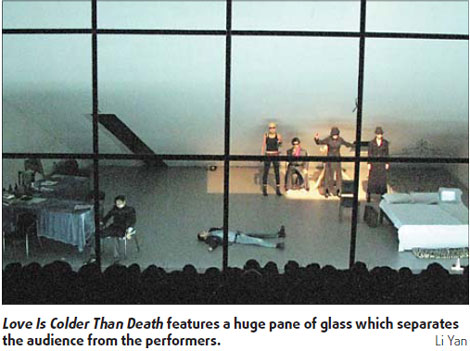

But the leading avant-garde theater director Meng Jinghui goes into reverse. His latest production, Love Is Colder Than Death, at Citycomb Theater until Nov 16, features a real glass wall at the front of the stage, separating the audience from the play.

It is definitely a fresh and interesting theater experience. Audience members are given earphones before entering the theater and there is a huge pane of glass at the front of the stage.

Then the space behind the glass is lit. Nine characters dressed in cool, European-styled costumes pose in a space that looks like an attic - two white walls and a roof. You hear the narrator speak in the earphones and he (sometimes she) directs the characters to move around the stage in a slow, insolent way.

A man named Franz is sitting in an armchair, reading the newspaper. Another man asks him for a cigarette. When he is told "no!" he takes the newspaper and drops it on the floor. Franz gets up and beats the guy up.

In the earphones you can hear every noise, like their heavy breathing, tearing the paper, throwing a chair.

Adapted from Rainer Werner Fassbinder's 1969 movie of the same title, the play centers on the pimp Franz, who is forced to work for a criminal syndicate of which he wants to be the boss.

The syndicate's Bruno and Franz become good friends. Franz even introduces his girlfriend Johanna to Bruno. They have an affair but Franz does not care. The three start to rob banks together, but eventually Bruno is shot dead by the police, while Franz and Johanna flee.

Like the movie, which worked hard to subvert conventional notions of movie storytelling, with lots of long pauses and stylized gestures, the play introduces a new performing style. The characters act in a rigid and awkward way, with an absent expression and vacant-looking eyes.

Like the movie, which worked hard to subvert conventional notions of movie storytelling, with lots of long pauses and stylized gestures, the play introduces a new performing style. The characters act in a rigid and awkward way, with an absent expression and vacant-looking eyes.

"Fassbinder once said when you read a book, you create your own images. But when a story is told on screen in pictures, then it is concrete and complete. He would prefer people to 'read' the film. And I agree with him, so I use the narrator," Meng says.

"Fassbinder is one of my favorite directors. He did theater before making movies. Those black-and-white images, those dramatic seconds and his mental domination, all fascinate me."

Love Is Colder Than Death was the first feature movie in Fassbinder's frantic career. It was booed at the 1969 Berlin Film Festival, but "from the insolent opening shot, or the final thrilling cut from car interior to bleak landscape, you can sense the utter confidence that burbled out of a gifted 24-year-old German director," Meng says.

"I changed almost nothing in the movie except the glass, the earphones, the sound and the awkward acting that I call for to make the production a theater experiment, challenging the audience's usual experience."

Indeed, the 90-minute play is challenging, partly because the plot is so simple, but with many flashbacks, repetitions, and no climax.

"The focus here is not the story. The plot is pretty basic and I think that was what Fassbinder really wanted to show with this film.

"After seeing this film you don't remember the plot so much as the feeling - or an attitude - of social isolation," Meng says.

(China Daily November 12, 2008)