|

|

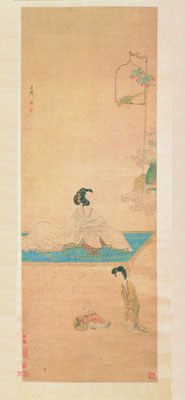

About 80 pieces of works by painters Cui Zizhong (left) and Chen Hongshou (below) are on display at the Shanghai Museum. |

The art world is fickle. Fads and phases come and go, but it's often not until years or decades later that true art and artists become recognized.

This is the case with the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) painters Chen Hongshou (1598-1652) and Cui Zizhong (1574-1644). Both refused to follow the mainstream and chose to go their own way, which led to a major breakthrough in Chinese paintings, says Zheng Xinmiao, director of the Palace Museum in Beijing, who was at Shanghai Museum recently for the start of an exhibition titled "Paintings and Calligraphy from Chen Hongshou and Cui Zizhong."

About 80 pieces are on loan from the Palace Museum for the exhibit.

During the late Ming, most artists were focused on landscapes, flowers and birds as they were popular at the time, however, Chen and Cui were obsessed with figures.

Zheng adds that Chen in particular would make a breakthrough that would be followed by generations of artists as "their vigorous works played a very important role in the history of Chinese painting." Chen applied the unparalleled baimiao technique, or drawing with a fine ink line, to his figure painting. This led Chen - who became a monk in the last few years of his life - to give the people depicted in his paintings exaggerated gestures and bizarre looks. It was totally new. Artists in the genre had previously focused on making everything look as realistic as possible.

|

|

About 80 pieces of works by painters Cui Zizhong (left) and Chen Hongshou (below) are on display at the Shanghai Museum. |

Chen Xiejun, director of the Shanghai Museum, says the two artists will be forever linked and that debate will continue as to who provided the bigger inspiration.

"Chen made a bigger contribution to the development of Chinese figure painting and exercised more influence upon later artists compared to Cui," says Chen Xiejun. "However, in the academic circle, there is still a prevailing saying: 'Chen in the south and Cui in the north'," which refers to where the artists were born.

The highlight of this exhibition, which includes about 80 pieces by Chen, Cui and their followers, is a hand scroll painting titled "Literati's Gathering in the Western Garden." It is a unique collaboration between Chen and Hua Yan (1682-1756), even though it was never intended to be when Chen started the painting. Chen, a native of Zhejiang Province, never completed the painting. About 70 years, Hua completed the work depicting nine scholars enjoying antiques in a garden. Each figure is accompanied with Chen's name written in light ink. The lines are clear, fluid, simple and graceful. Hua admired Chen's art and borrowed his technique to complete the painting. Nonetheless, Hua added some of his own flourishes to the piece.

Women were another popular subject for Chen in his art. The women in his paintings always had glossy, cloud-like hair, charming faces, arched eyebrows and small mouths. They were frequently depicted catching butterflies, holding flowers or fiddling with plums.

Cui, who was born in Laiyang in Shandong Province and moved to Beijing early in his life, preferred to include famous literati in his paintings. His characters often have a narrow frame and peculiar positions. He was also skilled at composing narrative scenes with elegant colors and nimble brush work.

Date: through February 7, 9am-5pm

Venue: 201 People's Ave, Shanghai Museum

Tel: 6372-3500

(Shanghai Daily January 7, 2009)