For art historians, Xu Beihong (1895-1953) is a pioneer of modern Chinese art whose style straddles the East and the West. But for the average Chinese, he is simply a master painter of galloping horses, roaring lions and lovely birds.

The largest retrospective show to honor the master painter has been drawing throngs of visitors from all walks of life since it opened at Yanhuang Art Museum in northern Beijing.

On display are over 80 of Xu Beihong's signature sketches, ink and oil paintings. The highlights are Xu's monumental ink paintings with historical themes like Yu Gong Moves the Mountain, Jiu Fang Gao and Galloping Horses, his oil works like Lady with a Flute and Self Portrait, and his early pencil sketches of horse herders and female nudes.

The exhibition coincides with the 60th anniversary of the founding of New China and the 90th anniversary of the May Fourth New Culture Movement.

In fact, Xu's career as an artist and his personal experiences are closely associated with Chinese history, says Peking University art professor Zhu Qingsheng.

"Based on his deep understanding and deliberate choice of Western painting traditions, Xu advocated a Realist approach and style for Chinese art. He played a pivotal role in transforming modern Chinese art," Zhu says.

Born in Yixing, Jiangsu province, in 1895, Xu grew up in an artistic family and showed talent at an early age.

He studied classic Chinese works and calligraphy with his father Xu Dazhang when he was 6 and Chinese painting, when he was 9.

In 1915, he went to study in Shanghai, a melting pot of Chinese and Western cultures where he met the scholar and political reformer Kang Youwei (1858-1927), who became his mentor and greatly influenced his thinking about the need to integrate Western practices and ideas into Chinese art.

"Xu felt that traditional Chinese art had become a mere copying of other paintings and was divorced from nature and social reality," says Central Academy of Fine Arts professor Huang Xiaoming.

"Xu was not the first to formulate the idea but he was one of the first to seek a solution and a direction."

Xu came up with the idea of applying Western scientific methods, using very precise anatomical proportions and integrating Western approaches, such as perspective and shading in his works, notes Huang.

In 1917, Xu traveled to Tokyo to study art. On his return to China, he began to teach at Peking University's art school at the invitation of principal Cai Yuanpei (1868-1940) in 1918.

Xu became one of the major figures of the artistic revolution of the May Fourth New Culture Movement in 1919.

The same year, Xu traveled to Paris on a scholarship from the Chinese government, studying oil painting and drawing at Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts.

His travels around Western Europe allowed him to observe and imitate Western art techniques.

Xu deliberately shunned the burgeoning experimental art scene of the Surrealists and Expressionists and instead embraced Realism.

|

|

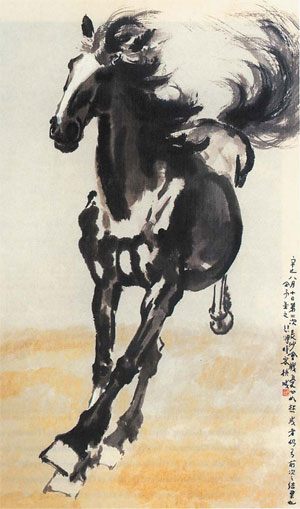

Chinese artist Xu Beihong excelled at capturing the vivid expressions, free will, endurance and vigor of galloping horses. |

"He felt that paintings should be understood by people," explains Professor Zhu. "And that is why he remained very much grounded in Realism throughout his life."

In 1927, nine of Xu's works were selected for exhibition in the Salon des Artistes Francais, making a great impression on the French art scene.

Xu returned to China in 1927 and, from 1927 to 1929, held many posts at institutions in China, including as a teacher at the South China Art Academy in Shanghai, which he co-founded, and at the National Central University (Nanjing University) in Nanjing, Jiangsu province.

In the late 1930s, Xu organized an exhibition of modern Chinese painting that traveled to France, Germany, Belgium, Italy and the former Soviet Union. During World War II, Xu traveled to Southeast Asia, holding exhibitions in Singapore and also in India.

Xu's magnificent giant canvases such as Tian Heng and his 500 Warriors and Waiting to be Freed, explicitly demonstrate a deft use of harmony and tranquility (characteristic of the Taoist influence in traditional Chinese art).

"Art was his tool to extol universal themes and human feelings," says his son, Xu Qingping

Xu's portraits bring out the individuality, thinking and spirit of his subjects as can be clearly seen in works such as Portrait of Li Yingquan, Rabindranath Tagore, Jiu Fang Gao and Woman Fetching Water.

In Yu Gong Moves the Mountain the artist praises the indomitable spirit of the Chinese people against Japanese aggression.

Xu also painted birds and animals such as horses, roosters crowing in the storm, birds fighting against the wind, wounded but still dignified lions - believed to symbolize the spirit of the Chinese people - and showed his love for his country during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45).

It is because of his deep observation and understanding of animals that Xu managed to capture their most vivid expressions, the free will, endurance and vigor of galloping horses, the shrewdness of cats, the sincerity and honesty of the ox, the clamor of ducks, and the strength of the eagle, notes Zhu Qingsheng.

After the founding of New China, Xu was named as the first president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts. He died of a stroke in 1953 at his home in Beijing.

Critics say Xu's influence extended beyond China in the early 20th-century. Many pioneering Singapore artists such as Chen Wen Hsi, Lee Man Fong and Chen Chong Swee have reportedly said that they "looked up to Xu as a mentor and a worthy peer".

Xu's paintings were immensely popular at home and abroad.

In November 2006, his Slave and Lion was sold at Christie's for 53.88 million Hong Kong dollars ($6.9 million). In April 2007, Put Down Your Whip was auctioned for 72 million Hong Kong dollars (about $9.2 million).

Faked versions of Xu's horses have sometimes surfaced in art markets but Xu Qingping points out that with careful study one can easily tell the original from the fake.

"First, my father never employed ready-made ink when doing ink paintings as fresh ink is a prerequisite for a good ink scroll. And the paper he used is rarely seen today," he says.

Also, "his inscriptions and stamped seals carry a unique style".

The most important thing, Xu Qingping says, is that "most fake painters are unable to depict the horses in strict accordance with the anatomical and perspective requirements, as seen in my father's works."

Running through April 10, Xu's retrospective show kicks off the Founders of Modern Chinese Art exhibition series at the Yanhuang Art Museum.

(China Daily, March 17, 2009)