| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

| Chinese and French Popular Prints Shining Together |

| Adjust font size: |

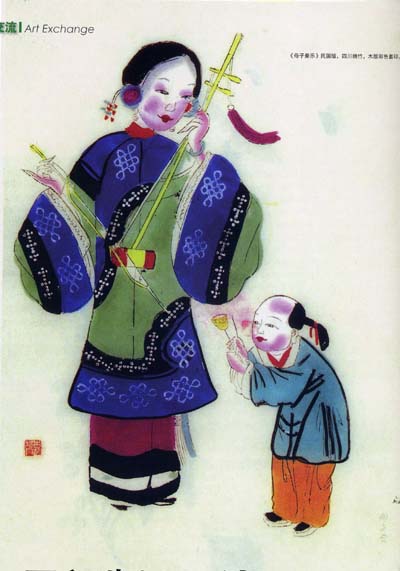

The Exhibition "Chinese and French Popular Prints," organized by the Central Academy of Fine Arts and French Cultural Centre, was opened recently at The Art Museum of Central Academy of Fine Arts, displaying collections of print works by Henri George and Wang Shucun. The print works from two printmaking centers, Yangliuqing in China and Epinal in France, document the ordinary lives of people living in two widely different countries in the past century. Originally, Chinese prints were carved into stone. The representative work is Wuruitu (Carvings of Five Auspicious Things, 171 B.C.) in Cheng County, Gansu Province. The printmaking technique then was not complete because of limited papermaking techniques. With the popularization of papermaking arts and woodcut techniques, the handicraft workshop for creating "menshen" (a door-god whose picture was often pasted on the front door against evil spirits), and "nianhua" (Chinese New Year prints) developed rapidly, and the woodblock prints came within reach of common folks. In France, printmaking appeared in the 14th century, focusing mainly on religion and decoration. Popular printmaking in the 15th century was intended to educate the illiterate rural population. The print works in Epinal recorded the folk customs, religion, history and even the popular novels at that time. Then blank pictures were changed into more complicated ones combined with words, decorations and lyrics. Wang Shucun, born in Tianjin in 1923 and Henri George, born in France in 1924, started to collect and study printmaking almost at the same time in two different countries. For these two collectors, the childhood years they spent in Yangliuqing and Epinal respectively are closely related to their interests in popular printmaking. Printmaking in Epinal originated in the 17th century. In 1938, the first Popular Printmaking Festival was held there and what impressed Henri George most was the paper-made soldiers, bombardiers, infantrymen and hussars, equal to the size of the real people. However, a real war, WWII broke out in 1939, and George was forced to go to Paris. After that, he began to study and collect popular French print works, even when printmaking gradually lost its popularity to newspapers, picture albums and cartoons. The collectable print works were only seen in special stores and at public auctions. Among various folk handicrafts like clay figures and paper cutting, the woodblock prints are Wang's favorite. With the invasion by the Japanese, he was driven by the wish to protect traditional heritage and went to study at the Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts and Central Academy of Fine Arts later. Now, Wang Shucun has published more than 50 books and more than 100 papers and he is also director of the China Folklore Society and a researcher in the China Art Academy. George has contributed to preserving popular French printmaking, especially those made in Epinal.

Compared with the mainstream arts, traditional folk art is also deeply favored by the common people. As stated in the introduction of the exhibition by Pan Gongkai, president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts: "It is due to the efforts of observant persons like Wang Shucun and Henri George that we are able to see the traditional arts today untainted by the clash between the east and west, and to think about another possibility of developing our tradition."

(Chinaculture.org July 25, 2007) |

| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

|

| Related Stories |

|