Growing threat to wetlands survival

In late April, a group of bird-watchers found that one of their usual observation spots - a 7-hectare lotus root field in Sanchakou village east of the Fifth Ring Road - was being filled with construction waste with the permission of officials. The waste will destroy the wetland that attracts the birds.

![Elks take a rest near a bank of a lake at Beijing Nanhaizi Country Park in Daxing district. [China Daily] Elks take a rest near a bank of a lake at Beijing Nanhaizi Country Park in Daxing district. [China Daily]](http://images.china.cn/attachement/jpg/site1007/20110530/0014222d98500f4d48ad12.jpg) |

|

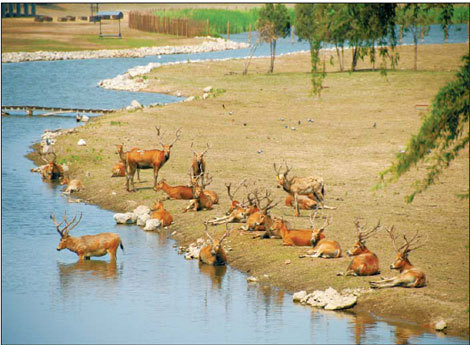

Elks take a rest near a bank of a lake at Beijing Nanhaizi Country Park in Daxing district. [China Daily] |

"I've been watching birds here for eight years," said Zhong Jia, director of China Ornithological Society. "More than 80 species use the small field as their resting place during migration every year."

Zhong said a lotus root field is all an artificial wetland needs to survive. The wetland in Chaoyang district's Sanchakou has existed for at least 50 years, but its days are now numbered.

"Residents older than 60 told me that the wetland has been there since they were small kids, which means it must have become a stable ecosystem," she told METRO.

Each truck of construction waste poured into the field earns 100 yuan for the local government. Almost 2 million yuan can be made from the whole field, Beijing News reported.

While wetlands around Beijing are used as landfill, a lack of water resources is threatening others. The situation is serious. If wetlands are the "kidneys of the earth", then Beijing's ecology is sick.

In the 1950s, wetlands made up 15 percent of the total area of Beijing, which experts said was "impressive". The figure dropped dramatically to less than 5 percent over the following 30 years, and bottomed out to less than 3 percent four years ago, according to data released by the Beijing bureau of landscape and forestry.

About 30 percent of those remaining wetlands are artificial. Even many so-called natural wetlands are really man-made. One expert said all the rivers and streams in the city have artificial riverbanks.

"Water area that was generated and preserved completely naturally can no longer be found in the capital," said Guo Geng, deputy director of the Beijing Milu Ecological Research Center.

Wetlands in Beijing hit their lowest point four years ago, when the total area bottomed out at 50,000 hectares, accounting for less than 3 percent of the city's total area, according to latest figures from the forestry bureau.

|

|

Milu deer relax by the side of a lake at the Beijing Nanhaizi Country Park in Daxing district, where work on the second phase of its development has already started. |

Since 2007, the capital's wetlands has been recovering and increasing, though at a very slow rate, said a senior expert on natural reserves, who is closely connected to the government but preferred not to be named.

The best example is the restoration of Nanhaizi Country Park in Daxing district.

Work on the second phase of the park's restoration has just begun, in a bid to transform the wasteland nearby into the largest wetland park in the capital in three years.

From the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the area around the park, about 20,000 hectares, had been wetland and was used as the royal chase, where Pere David's deer (Milu deer), one of the rarest animals in China, used to live, Guo said.

"In recent decades, the land had become paddy fields and was later transformed into an illegal refuse landfill after it dried out completely," said Guo, who is also a member of the Beijing committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, the nation's top advisory body.

But in late 2006, a small wetland park, about 65 hectares and dedicated to the precious deer, was opened to the public for free. In 2009, the municipal government released a plan to restore another 1,100 hectares of the Nanhaizi area into wetlands again.

The first phase of the planned large wetland park was opened in September 2010, while construction work on the second phase continues.

"Projects such as the relocation of residents near Miyun Reservoir and Guanting Reservoir, and the restoration of Yongding River, have also helped ease the harsh situation of the capital's wetlands," said the senior expert.

As the government has been trying desperately to save the city's "kidney", the situation facing the city now could not be worse. Although still alive, the remaining wetlands face a grim future.

Zhang Xiang at the Beijing-based environmental NGO Da'erwen, said some of the wetlands are pumping up underground water to survive, according to the organization's latest investigation.

"It is such a weird phenomenon that we found during our research into wetlands in Beijing," Zhang said. "Because one of the main functions of wetlands should be to supplement underground water."

The NGO found this situation in Hanshiqiao wetland. At almost 2,000 hectares it is one of the largest wetlands in the city.

"Our research has just begun. And I believe Hanshiqiao is not the only wetland that lives on underground water," said Zhang.

He is correct, because Milu Park, the small wetland that covers less than 70 hectares, also relies on underground water as one of its main water sources, said staff members at the park.

"It is high time everybody took action to protect wetlands," said bird-watcher Zhong. "And I'm not saying this for the birds, because finally it's going to be us humans who will pay the price."

The vanishing of Beijing's wetlands may not be vital if we look at it from a national perspective. After all, the city's wetlands make up only about one-thousandth of the total area of wetland in China, said the senior expert.

"But those who have lived in Beijing for decades may have the feeling that the city is a lot hotter and drier, with higher humidity than before," he said. "We are all familiar with the decline of underground water levels in the city. All are consequences of diminishing wetlands."

He said the preservation of wetlands is closely related to the usage of water resources in a city. And in the case of Beijing, the key problem is population.

"With the population growing to 20 million so quickly, it's extremely difficult to talk about solutions to save the wetlands, because many of them have been sacrificed for residential areas, and most of the water has to be stored in reservoirs," said the expert.

He also mentioned the lack of legal regulation in wetland protection, emphasizing that draft legislation had been finished 10 years ago, but there has been no obvious progress since then.

Zhong from the China Ornithological Society said another important reason for the vanishing of wetlands in Beijing is insufficient research.

"At the China Natural Reserve Forum on May 22 and 23, almost nine out of every 10 delegates were bird-watchers rather than real wetland researchers," she said.

The senior expert who did not want to be identified said he sees the city's wetland protection going nowhere if Beijing continues to develop without taking into account its level of resources.

"There is no way out if the city continues to expand, and not only for wetlands," he warned.

0

0

Go to Forum >>0 Comments