If you want to hear about the woes of environmental protection officials battling against local leaders driven by GDP growth, forget about Zhang Yongze.

The director of the environmental protection bureau of the Tibet autonomous region has a very different story to tell.

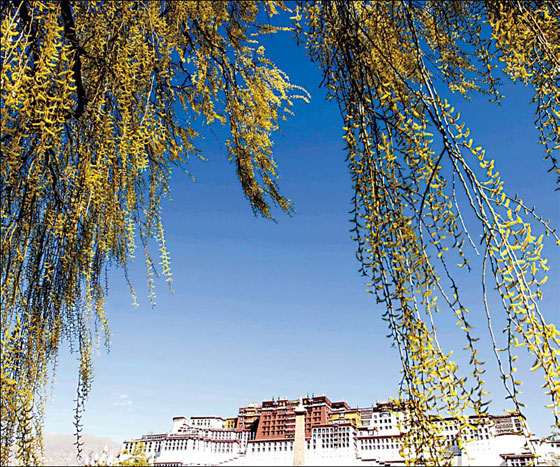

Green trees and blue skies such as these near the Potala Palace are a common sight in Lhasa these days. In recent years, the central and local governments have spent billions of yuan to clean up the environment in Tibet. [Xinhua]

Across China, environmental watchdogs have a difficult time dealing with local administrators preoccupied with boosting growth indices. They sometimes have to risk offending the latter and being sidelined, or shut up and move elsewhere.

But that has never happened to Zhang, he said.

"I feel really fortunate and proud being in this position," he told China Daily.

His pride is based not only on the fact that Tibet has one of the world's best-preserved ecosystems, but also that it has only once experienced bad pollution.

That was on March 14, when sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide levels in the air around Lhasa were more than twice the average, according to figures from the local environmental department.

"Actually, environmental conditions here have been improving over the years," Zhang said.

Zhang, who got his PhD in water pollution control from Sichuan University in 1997, and volunteered to leave the Beijing-based Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences for Lhasa the next year under the national Aid-Tibet program, has plenty of numbers to illustrate his claim.

In the 1950s, forest coverage in Tibet was less than 1 percent; now it is more than 11 percent, he said.

Thanks to increased vegetation, there has been a dramatic drop in the number of dusty days. For example, 30 years ago, Lhasa used to get 32 more dusty days a year than it does now, he said.

In addition the regional government has also been developing alternative energies and examples are "omnipresent" throughout Tibet, he said.

From the residential communities of downtown Lhasa to remote homes in the countryside, solar stoves and power-generating units can be seen in use. Windmills can even be spotted in some parts of Nagqu, he said.

Furthermore, local authorities have built 14,800 methane-producing facilities to provide clean energy for more than 70,000 farmers and herdsmen, he said.

"Alternative energies have greatly facilitated the protection of the natural vegetation in agricultural and pastoral areas," Zhang said.

Tibet's 40 nature reserves account for more 34 percent of the region's territory, he said.

"There is no match anywhere in the country. The national average is about 15 percent," he said.

Zhang said he is accustomed to being the envy of his counterparts both within and outside the region.

"I hear them saying jealously to me that 'you are the luckiest'," he said.

"And I totally agree."

To illustrate what he called a "high-profile consensus" on building Tibet into an ecological protective screen for the country, Zhang quoted the region's top official.

"Chairman Qiangba Puncog has a well-known saying that goes 'We should not accept any project that compromises our environment, even if it is digging for gold'," Zhang said.

On January 1, 2006, the regional government imposed a permanent ban on the mining of gold dust, and on Jan 1, 2008, extended it to placer iron, he said.

"The government has taken an extremely prudent approach to development planning," Zhang said.

"There are bans on high-polluting and high-energy-consuming industries such as papermaking and chemicals. During the 10th Five-Year Plan (2001-05) period, we closed down nine cement production facilities, five small iron works and four paper mills," he said.

Three small cement factories in Lhasa's north suburb have been closed down and the one remaining plant in the west suburb is operating without releasing smoke or dust. It will later be moved away from the city, he said.

"You just don't see industrial chimneys in Lhasa these days," he said.

Prominent on Zhang's list of achievements is the leading role Lhasa played in prohibiting the use of disposable plastic bags and coal-burning boilers.

"We were the first of the provincial capitals to ban plastic bags," he said.

"In the past, on windy winter days in particular, you could see all colors and sizes of plastic bags waving from tree branches and in bushes. Now, they are gone."

Now, when you return from shopping trips in Lhasa, your purchase will no longer come with plastic bags. Instead, you get reusable non-woven fabric bags.

The latest pollution-control moves include the building of garbage and sewage treatment facilities in major cities and towns, which were simply nonexistent in the past, he said.

Money is no problem, he said.

During the 10th Five-Year Plan (2001-05) period, the central and regional governments spent 2.4 billion yuan (US$343 million) on environmental protection. Last year, the spending was 480 million yuan, Zhang said.

Also, of the 180 projects the State Council has endorsed for Tibet's 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-10) period, 23 relate to environmental protection, he said.

The central government will spend more than 10 billion yuan during the 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-10) period on environmental protection in Tibet, he said.

"Tibet cannot afford not to develop, but neither can we afford to damage the fragile environment, which may prove irreparable once done," Zhang said.

"But we can manage it pretty well as long as we exert strict monitoring and control."

When asked if he thought the development of the Qinghai-Tibet railway had had a negative impact on the environment, he said such a claim was "pure nonsense".

"You can see for yourself anywhere you go," he said.

"The intact vegetation and undisturbed wild animals, like Tibetan antelopes, to be found along the railway, as well as the migratory birds you can see at the Dragon King Pond and on the Lhasa River tell you all you need to know."

(China Daily April 25, 2008)