Some 5,000 years ago, on a day with weather much like today's, a prehistoric person tread high up in what is now the Swiss Alps, wearing goat leather pants, leather shoes and armed with a bow and arrows.

The unremarkable journey through the Schnidejoch pass, a lofty trail 2,756 metres (9,000 feet) above sea level, has been a boon to scientists. But it would never have emerged if climate change were not melting the nearby glacier.

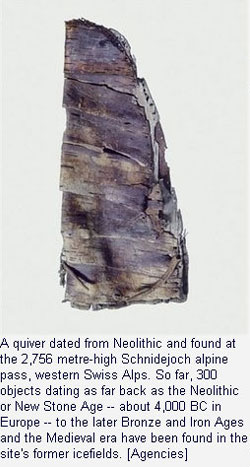

So far, 300 objects dating as far back as the Neolithic or New Stone Age -- about 4,000 BC in Europe -- to the later Bronze and Iron Ages and the Medieval era have been found in the site's former icefields.

"We know now that the discoveries on Schnidejoch are the oldest of this kind ever made in the Alps," said Albert Hafner, an expert with the archaeology service in Bern canton.

They have allowed researchers not only to piece together snapshots of life way back when, but also to shed light on climate fluctuations in the past 6,500 years -- and hopefully shed light on what is happening now.

"For us, the site itself is the most important find because we have this correlation between climate change and archaeological objects," Hafner said.

"We know that people were only able to walk on this site when it was relatively warm," said Martin Grosjean, executive director of a national network called Swiss Climate Research. "When it was too cold, the glacier advanced and it was not a passable route."

Scientists have long known there were periods of warmer weather in the region but the artefacts allowed them to identify the exact years, when the site would have been passable on foot.

According to Grosjean, such data could help sharpen forecasts for the future by taking into account patterns of natural temperature fluctuation.

The treasure trove preserved in the icefields was discovered after two hikers noticed a strange piece of wood lying upon some stones in 2003.

It turned out to be a quiver -- a case for arrows -- made from birch bark and dating as far back as 3,000 B.C. Hafner said this object may be the most significant single discovery at the site.

"It is the only quiver found that is made of birch bark. It is unique in Europe," he said.

Since then, even older objects have been excavated, including a wooden bow estimated to predate by 1,000 years the famed "Oetzi the Iceman" -- a 5,100-year-old frozen body found high in the Tyrolean Alps on a glacier straddling Italy and Austria in 1991.

Experts have deduced that many of the most valuable items may have originated from one ill-fated person, probably carrying the quiver, bow and arrows and clothed in leather pants and shoes.

"We think the person may have been killed during an accident because there were several objects from the same period found on the site," said Hafner. "It is unlikely that people would be leaving these objects so high up in the mountain."

The leather samples are also the oldest of their kind ever found, said Grosjean. "Leather decays easily in ambient temperatures. We know there were villages by the lakes in Switzerland but we've never found such leather objects," he said.

Analysis showed the pants' patch was made from a domesticated goat that resembled a breed recorded in Laos in those days.

"But the chances that the goat migrated from Laos are very slim. It could be a species that we had never before recorded to have been present in the Europe. Or its lineage may have died out since," said Grosjean.

Five years on, discoveries continue as the glaciers retreats.

"Last week, we found another Roman coin," said Grosjean, while Hafner said talks were underway with several museums on a future exhibition of the finds.

And with climate change, more such sites could emerge.

"The leather pieces are the oldest such finds now but maybe in the coming years, with other glaciers retreating around the world, they may not be the oldest for long," said Grosjean.

A recent UN Environment Programme report said by the end of the century, swathes of mountain ranges worldwide risk losing their glaciers if global warming continues at its projected rate.

"The ongoing trend of worldwide and rapid, if not accelerating, glacier shrinkage ... may lead to the deglaciation of large parts of many mountain ranges by the end of the 21st century," the report warned.