In late March, the State Council, China's Cabinet, approved Shanghai's plans to develop into one of the world's top financial and shipping centers by 2020.

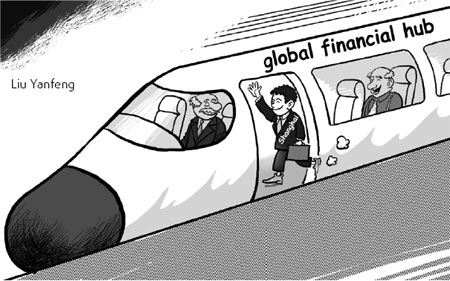

Such efforts are not new. Since the opening up and reforms began 30 years ago, China has piloted many financial reforms in Shanghai. In the early 1990s, the Shanghai municipal government mapped out a long-term development blueprint. So how can Shanghai expedite its development to become a global financial hub?

Since the near-meltdown of the global financial system in the fall of 2008, leading financial hubs have been trying to cope with a growing brain drain. Established centers such as New York and London have been hit hard by the financial crisis, the worst since the Great Depression.

The new financial industry that will emerge from the collapse in the US, Western Europe and Japan will be more tightly regulated and far less lucrative than it had been before the global economic recession. As a result, young financial talent is migrating to other cities and other industries.

Though financial centers compete with each other, the competition is not necessarily a "zero-sum" game. Global financial hubs can play different roles. Some focus on niche segments or are regional, only a few can offer global services.

At the global level, the competitive gap between New York City and London, as well as Hong Kong and Singapore has narrowed. Huge investments and the rise of Islamic finance have given rise to new financial industries in the Persian Gulf.

Before the economic crisis, the top three cities likely to be significantly more important over the next two-three years were believed to be Dubai, Shanghai and Singapore. In the long run, Singapore and Dubai both have great strengths in financial services. The short-term picture is very different.

Since late 2008, Singapore has been trying to cope with the collapse of export-led growth, while Dubai's aspirations have been deferred because of the downturn in global trade and the weak real estate and construction sector. On the other hand, Shanghai has benefited from China's growth despite the global recession, and it has been contributing to that growth as well.

Shanghai is already China's financial hub, home to the country's largest stock market, its major futures market for metals and energy, its gold bourse and its foreign exchange center. Given the State Council's support and Shanghai's historical efforts to become a global financial center, how could the city achieve its goal?

There are four necessary preconditions for success: making the yuan fully convertible, Shanghai playing the leader in China's financial reforms, taking additional policy measures to step up development, and embracing change.

The Chinese government has been moving fast toward making the yuan fully convertible. In April 2009, five major trading cities (Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Dongguan and Zhuhai) got the central government's nod to use the yuan in overseas trade settlement. That's a critical move toward making the yuan an international currency.

Based on World Economic Forum data, China's financial sector is relatively best in banks, financial stability, business environment, as well as size, depth and access of the sector (about 70-85 percent of the world's leading financial systems). The performance is relatively weakest in institutional environment, non-banking intermediaries and financial markets (about 45-55 percent of the world's leading sectors).

The good news is that much can be done in both cases. In institutional environment, for instance, special attention could be (and in several cases, is already being) directed to capital account liberalization, corporate governance, legal and regulatory issues, contract enforcement, and domestic financial sector liberalization.

Shanghai should not seek to emulate Wall Street and London as development models without reservations because it's the leading global financial hubs that contributed to the global financial crisis. Indeed, the crisis raises serious questions about the global acceptance of the "free-market" model of finance.

China's preference for gradual change and prudent regulation - "crossing the river by feeling the stones" - may prove wise in the long term.

The attractiveness of the global financial hubs can be improved in several ways, and Shanghai is well placed to implement these lessons.

Good quality basic infrastructure is essential, but "lifestyle" infrastructure - housing, schools and leisure facilities - is vital, too.

Financial services skills (IT, legal, accountancy and actuarial professionals) are essential, but as the ongoing crisis has demonstrated a balanced regulatory environment with knowledgeable people overseeing markets is equally necessary.

There is also the issue of mindset. Until recently, the global financial hubs of the US and the UK - as epitomized by Wall Street and London - exhibited signs of home bias, or a tendency to rate one's own center more highly than other people do. That mindset is closer to arrogance.

In order to establish its position regionally and to demonstrate true leadership, Shanghai should reject and transcend the home bias of the current global centers and embrace a new mindset of openness and cooperation with the world. That would be well in tune with the emerging multi-polar world and Shanghai's historical legacy as an open international city.

The global financial crisis has left "no place to hide". In the advanced economies, a fragile recovery and jittery markets only contribute to uncertainty. In the past, the rankings of the leading financial hubs changed slowly. Today, change is pervasive.

Shanghai's stability reflects certainty amid uncertain times. In order to further refine its competitive positioning, the city should emphasize its financial stability and long-term potential of economic growth. In a world of stagnating growth, these strengths make Shanghai immensely attractive.

(China Daily June 16, 2009)