One August morning in 1944, a timid schoolboy from suburban

Shanghai went to visit his classmates in the middle of the

Japanese-controlled metropolis.

What happened on Feng Yiping's journey has left a deep scar on

his life.

Feng was kidnapped by Japanese soldiers and later became a slave

laborer at the Kakeda coalmine in Kuriyama, Yubari, on the island

of Hokkaido, along with hundreds of other Chinese citizens.

"Over 60 years have passed. But I am still haunted by the

hellish days I spent at the Japanese coalmine," the 77-year-old

told China Daily.

On that fateful day in 1944, Feng had his money and ID card

confiscated by Chinese guards who had collaborated with Japanese

army. Empty-handed, he kept walking down Nanjing Road and was

stopped by Japanese soldiers at the Sichuan Road Bridge.

Unable to show his ID card, Feng was taken with 300 others to a

concentration camp near Hongqiao and stayed there for more than two

weeks. One night at bayonet point, they were marched onto a cargo

ship half-filled with iron ore. After spending more than 20 days at

sea, the ship reached a Japanese port.

"The first night on the Japanese soil, every one was sleepless,

without any idea of what life would be like," Feng says.

The next day, they were transferred to a train that took them to

the Kakeda coalmine at Kuriyama, in Hokkaido. The 300 kidnapped

Chinese were then divided into six working groups and each was

issued a worker number.

Feng was put in Group One and given the worker number 41.

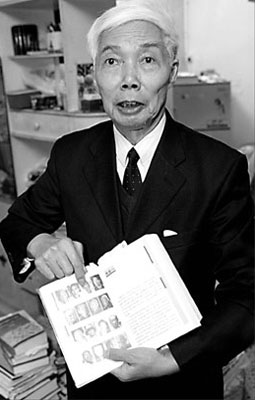

Feng Yiping shows He

Tianyi's book Oral History of Chinese Slave Laborers in Japan

during WWII, which includes Feng's experience. (photo: China

Daily)

Not far from the coal pit, rows of simple, wooden huts were

built for the laborers to live in. The huts, with 50 workers

crammed in each, were behind high fences in isolated camps with

armed guards.

"We did not have enough clothes and all the forced laborers were

in rags," Feng says.

They were each offered a blanket. When it was too cold, they

would have to work with their blankets wrapped around them.

"We barely had personal belongings," says Feng, who added that

the daily ration for every laborer was less than 25 grams of rice,

carrots or potatoes.

Most of the time, they had to fill up on chaff, herbs and bark.

"I always felt hungry," Feng says.

Feng and his fellow laborers were ordered to go down into the

pit at about 4 or 5 in the morning and usually got back to their

huts at about 11 at night.

"Some of my fellow laborers got killed by the blasting dynamite

or by falling chunks of coal in the pit."

Feng and other Chinese forced laborers worked day and night

shifts. "If you failed to meet the quota, the Japanese would force

you to keep working."

When the laborers returned from a day's work, they would be

covered with thick coal dust.

"Only the rolling eyes are recognizable. And when you spat,

you'd find coal dust in the phlegm," Feng recalls. Besides the

terrible working and living conditions, the Japanese treated the

laborers cruelly, Feng says.

The laborers were not given water to drink. Instead, "we drank

water dripping from the cracks on the shaft, or the water running

along the main shafts."

Nor could they bathe and as a result, lice, fleas and bedbugs

were very common.

"In their eyes, we were not humans but beasts that knew about

coal cutting; but in my eyes, they were lower than beasts," Feng

says.

If a Chinese laborer fell sick, it would usually cost him his

life.

"Many people who were ill never recovered. Instead, they died of

illness or hunger," Feng says, adding that three of his fingers on

the left hand were cut by an angry Japanese overseer and have never

fully recovered.

Feng remembers that five laborers attempted to escape. When they

were recaptured, they were beaten till they passed out. The men

later died in the freezing cold.

Feng admits that at one point he tried to take his own life but

was stopped by fellow laborers.

Fei Duo (worker number 70) and Shan Yaoliang (worker number 71)

used to be primary school teachers. In a small notebook, they wrote

information about dead laborers, such as their names, their worker

numbers, where they probably lived in China and how they lost their

lives.

Fei passed the notebook to Feng before dying of hunger.

"Little Feng, you are the youngest. If some day you go back to

our motherland, take this notebook back with you. We must let

people know about our suffering here," Fei said.

Despite having doubts of whether he would make it out of the

camp, Feng says he was determined to carry out the task.

He hid the notebook under his tatami bed and told two of his

most-trusted fellow laborers.

According to Feng's remaining record, during their stay at the

Kakeda coalmine, at least 98 out of the 300 Chinese died.

Feng and his fellow laborers worked day after day until around

August 1945 when their hours in the pit were cut back.

"We came out of the huts at 8 am and returned to the huts around

5 pm. We even saw sunsets sometimes," Feng says. "We sensed that

something must have happened outside."

On September 15, the Japanese unexpectedly declared a day off.

at 9 am, two American soldiers drove a jeep into the mine. They

came in search of missing comrades.

The groups of Asians in rags soon caught their attention.

"Where are you from?" one of the Americans asked.

"We are from Shanghai, from China," a Chinese laborer who spoke

English answered.

Feng and his fellow laborers were told that Japan was defeated

and they were free to go home.

On hearing the news, all of the laborers ran out of the huts,

and embraced each other.

In October 1945, Feng and some 3,000 Chinese laborers from

different working sites in Japan were sent back to Shanghai by

Japanese ships. Without decent clothes, they had to wear Japanese

army uniforms.

Arriving at his home in suburban Shanghai, Feng found his mother

on her deathbed. A month later, she passed away.

Feng later learned that his mother fell ill soon after his

sudden disappearance.

For a long time after his return, Feng dreamed of his days at

the Japanese coalmine and woke up screaming. He found it hard to

discuss and even more difficult to control his emotions.

Gradually, he became reticent, heavy-hearted and spent most of

the time studying at high school.

"Studying was the only way I could find to help heal my wounds,"

Feng says.

In 1949, he changed his name from Feng Yonggang to Feng Yiping

(literally meaning a piece of floating duckweed).

"I wanted to break away from my painful past and start a new

life," Feng says.

In September the same year, Feng passed the entrance exam for

Zhenjiang Medical College in Jiangsu Province, ranking 39th out of

the hundreds of candidates.

"I thought that even if I didn't become a doctor in the future,

I could at least improve my own health," says Feng, who after his

graduation in 1954, worked for the Nanjing Medical College. Later

he worked briefly in Beijing, and finally settled in Guangzhou in

1987.

First majoring in urology and later in andrology, Feng rose to

become a renowned medical professor and surgeon with the No 2

Hospital attached to Guangzhou Medical College, South China's

Guangdong Province.

Sixty years later, Feng is still haunted by his ordeal.

"What can I do about this notebook and the 98 deceased laborers

I knew about? I just cannot let go of the past," he says.

Even today, the families of the forced laborers who died in

Japan may have not known about their whereabouts or what happened

to them. "I have the responsibility of letting the world know about

the truth," Feng says.

In May 1979, Feng wrote a letter in Chinese to the Tokyo-based

Japan-China Friendship Association about his experience as a

wartime laborer and the notebook he has kept for decades.

The letter was translated and printed in the Japanese newspaper

in Japan and China on July 15. "The records from Feng are

invaluable evidence and will be kept with great care," an official

wrote about his published letter.

In April 18, 1990, Feng was invited to attend a memorial

ceremony at another coalmine in Kumamoto, Kyushu, where he showed

the notebook.

"Several Japanese journalists interviewed me, asking me about

200 questions," Feng says.

"Later, I learned that only five of the media outlets ran the

interviews. I wish more Japanese could read my story."

In July 2005, Feng donated the worn-out notebook he had kept for

more than half a century, to the Shanghai Memorial for the War of

Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

From August 6-9, 2006, he traveled again to Tokyo, attending

memorials for the forced laborers who were buried on Japanese

soil.

According to statistics from the Foreign Ministry of Japan,

between April 1943 and May 1945, at least 41,762 Chinese citizens,

in 169 batches, were captured. Of these, 3,470 died at sea and

38,117 were taken to Japan as slave labors. Of these, 6,830 never

made it back to China alive.

"I think it is a big mistake that the Japanese government

refuses to recognize the war crimes it committed during WWII on

Chinese people," Feng says.

Last week, he attended a series of commemorative events for the

Nanjing Massacre, including an international symposium on the

Japanese invasion.

"In my opinion, we should not hate the Japanese people. The

militarist extremists are to blame for the inhumane wrongdoings and

tragedies Chinese have suffered," Feng says.

(China Daily December 17, 2007)