Lunar New Year's Eve, the last day of the old year, is one of China's most important traditional holidays. Homes are spotless inside and out, doors and windows are decorated with brand new Spring Festival couplets, New Year's pictures, hangings, and images of the Door God, and everyone dresses up in new holiday clothes that are decorated with lucky patterns and auspicious colors.

Legend has it that long ago during the age of great floods, there was a vicious monster named Nian, which means "year." Whenever the thirtieth day of the last lunar month arrived, this monster would rise up out of the sea, killing people and wrecking havoc in their fields and gardens. The people would bar their doors before dark and sit up all night, coming out the next day to greet their neighbors and congratulate them on surviving.

Once on the last night of the last month, Nian suddenly burst into a small village, devouring almost all the people who lived there. Only two families emerged unscathed. The first, a newlywed couple, avoided harm because their celebratory red wedding clothes resembled fire to the monster, so it did not dare to approach them. The other family was unharmed because their children were playing outside setting off noisy firecrackers, which scared the monster away. Ever since, people have worn red clothes, set off firecrackers, and put up red decorations on New Year's Eve to keep the vicious monster Nian away. Later, according to the legend, the Emperor Star deity struck Nian down with a flaming orb and bound him to a stone column. Only then was there peace in the world. Now, people stay up all night and burn incense on New Year's Eve, entreating the Emperor Star to descend to earth and protect them.

|

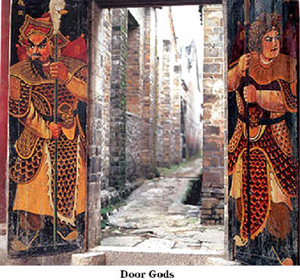

Every year on New Year's Eve, people paste up images of the Door God on the entrances to their homes. The Door God, or guardian of the threshold, is a very old deity. In its earliest incarnation, it was embodied in the door itself. The Door God was first portrayed in human form during the Han Dynasty, first as the warrior Cheng Qing, and later as Jing Ke. The door gods of the Northern and Southern Dynasties were named Shen Tu and Yu Lei. During the Tang Dynasty, two great generals named Qin Shubao and Yuchi Jingde were in charge of protecting the officials of the imperial palace. Emperor Tang Taizong (Li Shimin) felt that the generals were working too hard, so he ordered their portraits to be painted and hung beside the palace door to assist them. The two generals thus became associated with the ancient guardians of the threshold, and have been known as door gods ever since. During the Five Dynasties Period, Zhong Kui became the new door god. The Song Dynasty saw the further development of existing guardians and protectors. In addition to door gods, images of the gods of Blessings, Prosperity, and Longevity, as well as the Ten Thousand Deities and the Three-Treasures Buddha, are often hung in living rooms and bedrooms. These guardian deities were thought to protect the household from evil influences and repel demons.

New Year's Eve is the time to put up new Spring Festival couplets for the coming year. Spring Festival couplets consist of two paper scrolls, inscribed with auspicious sayings, pasted vertically on either side of the door. A shorter horizontal scroll is often pasted across the top. Like images of door gods, Spring Festival couplets were thought to protect the household from evil. According to ancient Chinese folk beliefs, ghosts and demons fear peach wood. Protective charms made of peach wood boards were therefore traditionally hung on either side of the door during the Lunar New Year festival. Later, images of the door gods Shen Tu and Yu Lei were painted on these boards.

During the Five Dynasties Period, Meng Chang, the king of Shu, ordered the scholar Xin Yinxun to copy some of the king's poetry onto a peach wood door charm. However, Xin Yinxun did not approve of the king's literary effort, and instead inscribed the following lines of his own: "The New Year is filled with holiday cheer; celebrations proclaim the coming of Spring." This was China's first Spring Festival couplet. By the time of the Ming Dynasty, Spring Festival couplets were popular throughout Chinese society. Some examples of popular couplets for Spring Festival are: "Another year passes above and below; Spring brings blessings to Heaven and Earth"; "Good fortune as deep as the Eastern Sea; long life as staunch as the Southern peaks"; "Firecrackers sound and the old year flees; the new year is welcomed through ten thousand doors."

|

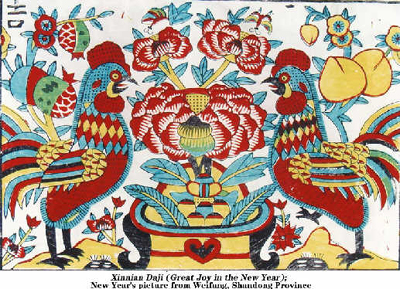

New Year pictures, as their name implies, are made especially to celebrate the Lunar New Year holiday. With the coming of Spring Festival, these pictures appear in households throughout the nation, their bold outlines and vibrant colors adding to the excitement of the holiday season. New Year pictures are an ancient Chinese folk art, reflecting the customs and beliefs of the common people and symbolizing their hopes for the future. New Year pictures, like Spring Festival couplets, trace their origins to China's ancient door gods. After a certain point, however, these pictures were no longer limited to depicting the various protective deities, and became increasingly rich and colorful. Among the common subjects of New Year pictures are "A Surplus Every Year," "Peace Year After Year," "Blessings from Heaven," "An Abundance of Grain," "Flourishing Livestock," and "Spring Comes with Good Fortune."

Papercuts made from lucky red paper are often pasted in windows and on doors to celebrate Spring Festival. Papercutting is an extremely popular Chinese folk art. Papercuts usually draw their subject matter from legend, opera, and the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac. Bold and expressive, they depict a range of lucky themes and beautiful dreams, adding color and verve to the celebratory spirit of Spring Festival.

The character "fu" means happiness and good fortune. It is as often used as a decoration during Spring Festival, expressing the hope for good fortune and a bright future in the coming year. In order to emphasize the significance of this character, it is often pasted on the door upside down. This is meant to cause visitors to remark, "Your fu is upside down," which is an exact homonym for the auspicious phrase, "good fortune has arrived."

In addition to door gods, Spring Festival couplets, New Year pictures, and papercuts, many families also paste up special decorations known as menjian on Lunar New Year's Eve for good luck. Made out of red or colored paper, these decorations consist of papercuts plus auspicious sayings, with a fringed bottom. Today, instead of the traditional menjian, many people put up "Chinese knots," a type of decoration made out of red cord tied into lucky designs.

|

Making offerings to the ancestors is one of the most important folk customs of Spring Festival. Traditionally, households prepared for New Year's Eve by bringing their family's genealogical records, ancestral portraits, and memorial tablets to the ancestral hall, where the altar was prepared with incense and offerings. In some regions, offerings were prepared for the deities of Heaven and Earth as well as for the ancestors. In other areas, obeisance was made to the Jade Emperor (the highest deity in the folk pantheon), and the Queen Mother of the West (wife of the Jade Emperor). The offerings, known as "offerings to Heaven and Earth," consisted of mutton, five types of cooked dishes, five colors of snacks, five bowls of rice, two date cakes, and a large steamed wheat-flour bun. The rite was performed by the head of the household. After burning three bundles of incense and bowing to the ancestors, prayers were offered for a fruitful harvest in the coming year. Finally, paper images of money were burned, the smoke carrying the household's prayers and salutations to Heaven. These Spring Festival rituals were a way of wishing the ancestors and deities a Happy New Year.

It was considered imperative to honor the ancestors during Spring Festival, both to remember previous generations and to ensure the continuation of the family line. However, regional differences produced widely differing traditions. In some places, the ancestors were honored before the New Year's Eve feast, while in others the ceremony was conducted at midnight on New Year's Eve. In yet other places offerings were made to the ancestors on New Year's morning, right before opening the door of the family courtyard. In Taiwan, the year's final offering to the ancestors was made in the afternoon of New Year's Day. In some regions, offerings were made to the ancestors at home on New Year's Day, after which the household would travel to the ancestral temple for further ceremonies. In some places, it was customary to conduct the ceremony at the ancestral graveyard, burning incense, making offerings, and bowing to the ancestors. Today, people usually pay their annual respects at the graves of their departed loved ones.

|

The traditional New Year's Eve feast, held on the evening of the last day of the lunar year, is one of the major events of Spring Festival, greatly beloved among Chinese families. Before dinner, it is customary to hold ceremonies honoring the ancestors and to set off firecrackers.

Several special traditions are associated with the New Year's Eve feast. First, it is a time when the entire family gathers together. Whether the meal is cooked and eaten at home or enjoyed at a restaurant, all members of the family, old and young, male and female, attend the feast. The evening before New Year's Eve, all visitors must return to their own homes for the New Year's celebration. A place setting is prepared at the table for any family members who are unable to get home for the holidays, symbolically filling their place in the family circle. Because it serves to bring the family together, the New Year's Eve feast is also called the Reunion Feast. After the meal, the adults give the children red envelopes containing gifts of New Year's money.

Second, the New Year's Eve feast includes a wide variety of delicious foods and drinks. After working hard all year, people can finally relax with their families and enjoy life. In some regions, it is traditional to drink a special kind of liquor, tushujiu, steeped with herbs, which is said to provide protection against disease in the coming year.

Third, the food served at the New Year's Eve feast has rich symbolic meaning. The dishes definitely include fish and chicken, since their Chinese names are homonyms for "abundance" and "good luck." In Taiwan, it is traditional to eat fish spheres (like meatballs, but made out of fish), whose round shape symbolizes the family circle and family reunions. The name for Chinese leek is a homonym for "a long time," so dishes made with Chinese leeks are eaten to symbolize long life. Turnips are another popular New Year's dish, because their name in Fujian dialect is a homonym for "good omen."

And of course, on New Year's Eve everyone must eat jiaozi, boiled dumplings.

Jiaozi (boiled dumplings stuffed with meat and vegetable filling) are also known as gengnian jiaozi (seeing in the new year dumplings). Although boiled dumplings have been a favorite food of the Chinese people for thousands of years, they have only been essential element of the lunar New Year's festivities since the Ming Dynasty. Jiaozi are the exact size and shape of the small gold ingots that were used for money in ancient China, so eating jiaozi satisfies the desire for wealth. Of course, jiaozi are also incomparably delicious, so on New Year's Eve, virtually everyone in China can be found eating this holiday dish. When vendors boil jiaozi to sell, they will often deliberately break one or two in the pot. But they do not remark upon this with taboo words, such as "break," "shatter," or "disintegrate." Rather, they say that the dumpling's filling has "burst," which in Chinese is a homonym for the auspicious phrase "to get rich."

There are many different regional customs concerning eating jiaozi to celebrate the lunar New Year. In some places, they are eaten on the last day of the year, and called tuanyuan jiaozi (reunion dumplings); in others they are eaten on New Year's Day and called nianfan (first meal of the new year). People in some regions traditionally eat jiaozi on the fifth day of the New Year. This day is known as Powu (Broken Fifth), so they are called powu jiaozi (Broken Fifth dumplings). And in some places, people eat jiaozi late into New Year's Eve and continue throughout New Year's Day, symbolizing continuing abundance from year to year. But the most common practice is staying up late on New Year's Eve wrapping, boiling, and eating dumplings to mark the transition between the old and new years. These jiaozi are called gengnian jiaozi (seeing in the New Year dumplings), signifying that the New Year will bring good luck and abundance.

On New Year's Eve, the house is brightly lit as the whole family stays up all night to see out the old year and see in the new. People do more than just sit around as they wait for the arrival of the New Year. There is plenty to eat and drink, including wine, cooked dishes, New Year's cake, boiled dumplings, fruit, and assorted snacks, and all kinds of games are played. Since it's nighttime, most of the games are played indoors. Popular games include Go, Chinese chess, card games, and mahjong. Before it gets dark, children ride bamboo horses, spin tops, and play games like "Eagle Catches Chicken" and "Blind Man's Bluff." As midnight approaches, the parents prepare the family altar. They then light incense and make offerings to the ancestors and auspicious deities, bringing the New Year's festivities to their peak. After the ceremony is over, everyone exchanges New Year's greetings and eats boiled dumplings. It is also traditional to set off fireworks and firecrackers on New Year's Eve. As it gets closer and closer to midnight, nonstop explosions fills the air and the sky is filled with a sparkling display.

Since the 1980s, it has become extremely popular to watch the annual "Spring Festival Gala Show" on television on New Year's Eve.