Structured to survive

- By John Ross

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, October 16, 2012

E-mail China.org.cn, October 16, 2012

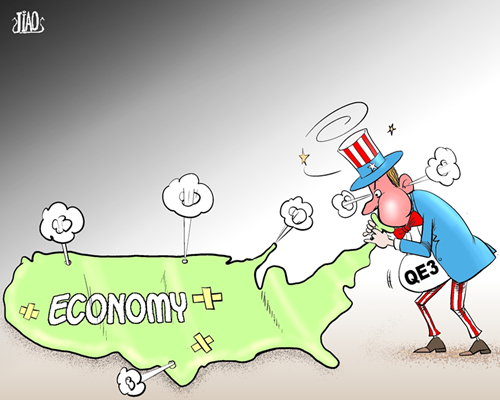

The IMF's recent meeting in Tokyo focused on the deterioration in the global economy; with G7 economic growth in the second quarter of 2012 only 0.1 percent and EU output contracting. Confronted with this, Western central banks have responded with a common policy - massive money creation. The US Federal Reserve launched QE3 - a $40 billion (250 billion yuan) per month open-ended purchase of mortgage-backed securities. The European Central Bank announced an unlimited program of Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) - the creation of money to purchase European government bonds. The Japanese Central Bank intervened in an attempt to lower the yen's exchange rate.

|

|

Beat the air [By Jiao Haiyang/China.org.cn] |

Such massive monetary injections necessarily affect not only the global economy but also individual markets. Mohammed El-Erian, chief executive of PIMCO, the world's largest bond investor, has cited one risk which is being created in the process. He said: "Essentially the Fed is inserting a sizeable policy wedge between market values and underlying fundamentals… In the process, many asset prices have been taken close to what would normally be regarded as bubble territory, with some already there." Western central banks are engaging in monetary easing on an unprecedented scale.

The reason for this is clear and illustrates the superiority of China's economic structure over Western ones. As the Wall Street Journal correctly put it: "Most economies can pull two levers to bolster growth - fiscal and monetary. China has a third option … accelerate the flow of investment projects."

Globally, the main economic feature of the financial crisis is a huge decline in investment. In developed economies all other major components of GDP are now above pre-crisis levels, except for fixed investment, which in inflation adjusted terms, remains $491 billion below its peak. It is the inability to reverse this fall in investment which is leading to near paralysis, or worse, in developed economies.

In contrast China's 2008 stimulus program, and the more limited economic boost launched in the middle of this year, tackled the situation directly via state decisions of increasing investment. As Western economies reject significant state investment on ideological grounds they are forced to rely purely on budgetary consumption measures and monetary expansion.

When the financial crisis erupted in 2008 almost all Western economies responded by simultaneously introducing ultra-low interest rates and expanding budget deficits, the latter financed via borrowing. But the scale of the economic downturn made it clear that such large borrowing would have to continue not for short periods, which would not create any great problems, but for a very prolonged one. Running budget deficits which in some cases approached or exceeded double-digit percentages of GDP would therefore hugely increase state debt. The IMF's latest World Economic Outlook rightly stressed that state debt in the U.S., Japan and many European countries is now around, or above, 100 percent of GDP.

At the IMF gathering, a sharp debate took place between those, led by Germany, who want rapid budget deficit cuts, and those, championed by IMF Managing Director Lagarde, who regard slower deficit reduction as a less risky strategy. But no mainstream Western government believed it could respond to the new global downturn with major new fiscal expansion. Therefore, in Western economies, monetary policy is the only available tool with which to fashion a response. Given the large scale of downward global pressures, Central Banks were necessarily led to a strategy of huge monetary creation.

Monetary expansion has so far not halted the slowdown of Western economies and it is creating a structural financial problem. With a prolonged period of financial decisions based on extremely low interest rates, and with money creation on such a large scale, there will be a series of financial collapses as soon as any attempt is made to raise interest rates. The global economy is locked into a prolonged period of ultra-low interest rates and expansionary monetary policy.

How does this affect China? One immediate risk is inflation. Even before QE3 was officially announced, media speculation preceding it precipitated a sharp increase in global commodity prices. The Dow Jones-UBS index of spot commodity prices rose by 18 percent between June and October, with even more rapid increases in key food prices following the additional impact of drought in the US. The resulting food price rises stimulated social unrest in the Middle East, South Africa and India. As China's CPI follows world commodity prices, China's economic policy must guard against inflationary risks.

However upward pressure on global commodity prices created by QE3 is countered by downward pressure due to the world economic slowdown. Global commodity prices remain 9 percent below the level reached in early 2011 when they propelled China's CPI to 6.5 percent in July. China is limited in the type of expansionary policies it can pursue due to the fact that it must exercise caution. So far, however, the international situation does not indicate that inflation in China is likely to become an insoluble problem.

The large monetary injections by the US, ECB and Japan pose other threats. Parts of the monetary emission will inevitably spill into other economies, including potentially China's, threatening to create asset bubbles. For this reason leading international monetary experts, such as Barry Eichengreen, have advised countries to strengthen administrative currency controls.

Given this situation, China's central bank has rightly been cautious with regard to monetary easing. Rather than making further reductions in interest rates, or cuts in reserve requirements, since July it has preferred to deal with domestic liquidity issues by short term monetary injections which can be reversed relatively rapidly.

Given the downward pressures from the world economy, China clearly must boost domestic demand. However, the Western Central Bank policies already described mean that this must largely be done by means which directly stimulate China's productive economy rather than by generalized monetary emissions. Given this, the key question becomes: How should such a stimulus be divided between investment and consumption?

China's former World Bank chief economist Lin Yifu has rightly argued that, for long-term economic reasons, an economic stimulus is better delivered via boosting investment rather than consumption. The same conclusion follows from trends already described in the business cycle since the financial crisis hit. Nevertheless, China has significantly increased its percentage of investment in GDP since 2008 and practical management factors must be taken into account - it is difficult to deliver very large increases in investment efficiently. For that reason, China's recent economic policy moves to moderately boost both consumption and investment are appropriate. Investment increases were included in measures adopted in the summer. Steps to boost consumption were taken by, for example, abolishing road tolls during China's recent Golden Week holiday - a measure designed to encourage tourism.

Massive monetary emissions by Western Central Banks are unlikely to lead to significant growth in their economies, given they fail to deal with the underlying problem of falling investment. They will, however, create problems for others in the world economy. No country, including China, can entirely escape all the problems which will result from the travails of struggling Western economies. But the structural superiority of China's socialist market economy over Western free market ones means that, as has been the case since 2008, China will continue to ride periods of economic turbulence far more successfully than other major countries.

The author is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:http://www.china.org.cn/opinion/johnross.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)