Pablo Neruda and the poetry of revolutionary struggle

- By Heiko Khoo

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, April 15, 2017

E-mail China.org.cn, April 15, 2017

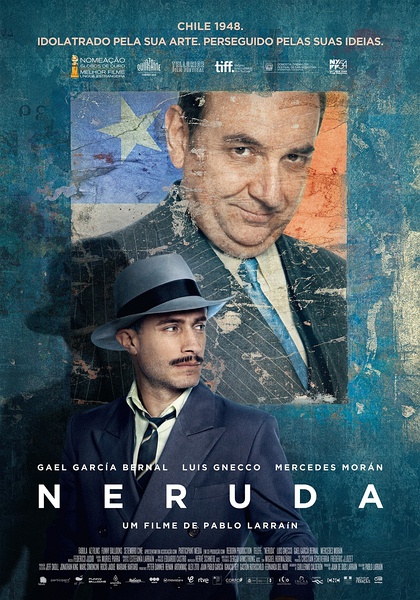

“Neruda,” the film, can help to keep the flame of revolutionary thought burning, and inspire new generations to find their voice. [File Photo]

“Neruda” is a film by the director Pablo Larraín. It examines a short period in the life of the Chilean poet and Communist Party Senator, Pablo Neruda. The story begins in 1948, when government repression forces the Party underground, and Neruda goes into hiding. And it ends with Neruda exiled in Paris after escaping from Chile.

The film is an anti-biographical and highly personal representation of Neruda and his environment, as imagined by the film’s director. It is beautifully filmed, and the script is carefully crafted – the product of years of research. Luis Gnecco, an actor normally cast in comic roles, plays Neruda.

This choice is fully justified, as Gnecco presents a serious persona, and this trait is commonly associated with the real character of great comedians. However, this sublimation of his normal role achieves its objective, as Gnecco’s eyes twinkle with a mischievous playfulness, which Neruda clearly exuded throughout his life.

This reveals the tension between Neruda as a revolutionary political animal, and Neruda as a man who lived, loved and laughed to the full.

Neruda was a profoundly human visionary, and his exuberant taste for the sensualness found expression not only in his poetic sensibility but also in his love life, which is painted with a hedonistic tinge in the film. This upset some in Chile, who prefer their heroes to remain sanitized icons – suitable to be presented as pure role models.

There is certainly plenty of unabashed sensuality in Neruda’s own autobiography, which includes many escapades and tales of erotic encounters. However, rather than corresponding to any misogynistic stereotypes, Neruda’s representations of the women he loved, are sophisticated and enigmatic, as befits the poet and the revolutionary. In the film, the poet and the revolutionary, are both at odds and in balance.

When Neruda is forced into hiding, he causes alarm among his entourage by his flagrant beaches of protocol, on issues affecting his security and safety. This does not go unchallenged. For example, his bodyguard reproaches him for a lack of humility, a criticism that he appears to internalize.

Then, a drunken female admirer asks him, if Communism means equality for all, does this mean equality at his bohemian and relatively well-off level, or equality at her level? After a considered silence, Neruda answers that it will be equality at his level.

As Communist Party members face increasing repression, and are incarcerated in prison camps and killed, Neruda writes and recites deeply moving poems that help to galvanize the mood of popular resistance in society. And, as the poor make these poetic verses their own, they become voices of rebellion, a cry of the oppressed, and a vision of change, which offers an alternative spiritual sanctuary to that of religious faith.

Neruda’s cheeky escapades defy the repression of the authorities and, like an infamous criminal he is determined to taunt the detective (Gael García Bernal) who is chasing him. Neruda leaves various clues in books and poems to entice his hunter to engage with his world. And thereby, he enters the mind of his enemy and eats away at his certainty of purpose and mission.

For Neruda, escaping capture is a game, whereas for the detective it is a chance to prove his competence and elevate his stature. The detective is performed as a simple, although functionally competent man. And Neruda makes it his mission to break down the armored character of this policeman, and thereby to humanize his enemy. Socialism, after all, must be able to neutralize or win over such functionaries and officials to its cause.

Since the death of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, and the fall of former president Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, the battle for socialism appears to have suffered a historic setback in South America.

Nevertheless, the continent continues to experience extreme inequality. Although left-wing governments and presidents awoke a mood of revolutionary hope, they failed to fundamentally change society. This is why the political pendulum swung back to the right. The majority still yearns for a better world, but their everyday personal struggles have replaced collective struggles.

“Neruda,” the film, can help to keep the flame of revolutionary thought burning, and inspire new generations to find their voice, by expressing the trials and tribulations of life, love and struggle, through the creative spirit.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)