An evergreen writer

At 56, the award-winning Wang Anyi has a formidable body of work to her credit that touches almost every aspect of life - from the ordinary to the bizarre.

|

|

Shanghai-based writer Wang Anyi, who has been tirelessly reinventing herself, says she's always "detached from the so-called trends". [China Daily] |

Followers of Wang Anyi's work cannot stop raving about the way she has evolved since 1976. That was when her first short stories, based on her time spent as a cellist in a cultural troupe in Xuzhou, then a soot-dusted town in Jiangsu province, were written.

Over the years she has proved her skills in every genre - from "scar literature", recounting the excesses of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), to tales about educated urban youth struggling to readjust to the home and hearth they left behind, from stories of women's sexuality and its myriad, sometimes bizarre, manifestations to avant-garde, unconventional forms of story-telling.

The secret of tirelessly reinventing herself, says Wang in a telephone interview from Shanghai, is to hold one's own. "I have always been detached from the so-called trends," she says, "perhaps because I am less influenced by the dominant ideology."

At 56, Wang has an enviable body of published work (100 short stories, more than 30 novellas, a dozen novels, 11 volumes of essays and various other compilations), besides the coveted Mao Dun Award, in her kitty, and yet refuses to slow down.

Her current engagement is a novel titled Scent of Heaven (Tian Xiang), set in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The novel of epic proportions revolves around three generations of women from the wealthy Gu family who develop the Gu school of embroidery, from which the intricate Suzhou-style embroidery has evolved.

The book has proved to be a labor of love for Wang. "This is indeed backbreaking work," the writer says. "It feels like climbing a mountain."

But then that is no surprise as Wang's journey as a writer has been about negotiating rough terrain and scaling heights. The daughter of two eminent literary personalities, Ru Zhujian and Wang Xiaoping (see other story), Wang Anyi, like many of her peers during the "cultural revolution", was sent to the countryside at 15.

While the wisdom acquired from shoveling earth on a famine-struck patch next to the Huaihe River, in the "Siberia" of Anhui province, went into stories like Wedding Banquet (Xi Yan), it wasn't an experience Wang would recommend. "It was hard and gloomy, without a modicum of pleasure," she says.

Being a musician in Xuzhou, where she chose to go because the offices were close to the railway station, a ride away from her hometown in Shanghai, was a shade better. This was where she met her future husband, Li Zhang, now an editor with a publishing house in Shanghai, with whom she has had a long relationship.

Besides, it enhanced her "knowledge and understanding of small towns in China's hinterland", she says. It is evident in the stories, Life in a Small Courtyard, and The Stage, a Miniature World, in which a group of actors rehearse, play, love, fall apart and reunite in a constricted space - a reflection of the theater of life played out universally.

Although she does not think her career as a musician impacted her writing, Wang speaks in musical metaphors. She says her "short stories are like ditties, novellas a single musical movement, and novels like orchestral compositions".

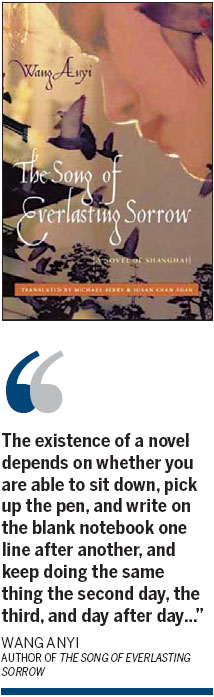

By extending that metaphor, one might say The Song of Everlasting Sorrow (Chang Hen Ge, 1995), the novel that is unequivocally her most outstanding work yet, is like an opera in three acts - complete with an intense tragic denouement and a cathartic end. It is a novel spanning 40 eventful and politically-turbulent years (1945-85), set in the generic Shanghai nongtang (alleyways), about the anonymous, inconsequential people whose little lives are played out on the margins of history.

The book was applauded as a modern classic, attracting both critical acclaim and commercial success and was adapted for film, television and the stage where the story of Shanghai girl Wang Qiyao - who seemed destined for fame and glory - could live on in myriad new manifestations.

Now 12 years later, Sorrow is still going strong, having sold more than 1 million copies. Even as critics celebrate this "Proustian" saga of love and longing - an insightful and evocative take on pre-liberation Shanghai evolving into reform-era Shanghai, brimming with atmospheric detail - Wang herself sees this success with a down-to-earth detachment.

"It carries some elements of popular bestsellers, like the twisted romantic love story. And it was published shortly before the death of Eileen Chang (1920-95)," she says, referring to the hugely popular writer whose tales of political intrigue and crimes of passion set in 1940s Shanghai and occupied Hong Kong have had an unbeatable afterlife, thanks to the celebrated film adaptations.

Ever since David Der-wei Wang, professor of Chinese literature at Harvard University, described Wang Anyi as "Eileen Chang's literary successor", turning Wang into a household name among literary enthusiasts in Hong Kong and Taiwan, the names of Chang and Wang are uttered in the same breath as if they were Siamese twins.

In fact, Chang's tragic and often moral tales of passion and betrayal replete with the old-world charm of 1940s Shanghai are vastly different from Wang's thoroughly de-romanticized take on the city.

"Shanghai is modern, old-fashioned and crude," Wang says. "It didn't evolve gradually, but shot to stardom with a sudden inflow of foreign capital. No other city in China is inhabited by such a well-developed urban petty bourgeois class (xiaoshimin) as Shanghai.

"Some say I have been writing sequels to Chang's stories - while her stories are set before 1949, I write about what her characters might have experienced in new China," Wang says. "Writing about the last years of pre-Republican China, Chang cannot help but take a grim view of things, because everything was on the decline. I live in a brave new world."

Her own relationship with the city, Wang says, "is dialectical".

The chair of the Shanghai Writers' Association since 2001, Wang insists she is still primarily a writer who in the first six years of her tenure published four novels and won the third Lu Xun Literary Award for her short story, Lover's Prattle in a Hair Salon (Falang Qinghua).

She was instrumental in starting a "Shanghai Writing Program" in 2008, inspired by the prestigious Iowa Writers' Workshop in the United States, which she attended in 1983 with her mother. Iowa was an eye-opener, says Wang, especially after she got to meet fellow writers from Third World countries. She was still nursing a grudge about getting a raw deal in her youth.

"But when I realized that everybody else had also trekked through trials and tribulations, I was able to adjust my perspective and see things in a larger context."

At the end of the day her success, as fellow writers like Liu Qingbang concede, boils down to relentless slogging. As she writes in the afterword of a novel Fierce Heroes Everywhere (Biandi Xiaoxiong): "The existence of a novel depends on whether you are able to sit down, pick up the pen, and write on the blank notebook one line after another, and keep doing the same thing the second day, the third, and day after day It will be non-existent, with even a slightest hesitation and vacillation.

"I made it, because I persevered."

0

0

Go to Forum >>0 Comments