'The Peony Pavilion' and the plight of women

- By Rory Howard

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, March 21, 2016

E-mail China.org.cn, March 21, 2016

|

Professor of philosophy at Wuhan University, Zou Yuanjiang, gave a lecture on the Chinese classic opera "The Peony Pavilion" at University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies on March 16.

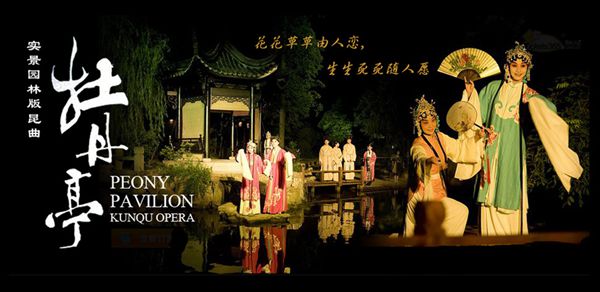

"The Peony Pavilion" is a tragic love story by Tang Xianzu, Shakespeare's Chinese peer. Professor Zou's visit to London coincides not only with the 400-year anniversary of the death of Shakespeare, but also of Tang Xianzu.

Tang's opera is the story of sixteen-year-old Du Liniang who, trapped by the strict Confucian morals of chastity, has love and lust awoken in her by a man she encounters in a dream after visiting the family garden for the first time. Awoken from the dream and torn away from this mystery man, Du is heartbroken. Heartbreak leads to the main character's death from starvation.

Why a young lady should dream of a man after visiting a garden is one topic that Zou expounds on.

Du's treatment has drawn the attention of female readers and viewers for over four-hundred years since the opera was performed. The opera is so moving that is has led to instances where performers have died as a result of the sadness they feel for the main character.

"The reason why Du Liniang's story makes women so emotional," Zou said, "is because these women share common experiences with [her].

"It is under the pressures of a specific cultural field that women of the Ming dynasty were subject to anguish and depression."

To the modern viewer it is not obvious what it is about pre-modern Chinese culture that causes anguished feelings for women.

A single line begins to explain how women lived. "Leaning against the window, alone and solitary"; "Solitude," Zou says, "is the traditional Confucian concept that calls for "a woman… to not leave her bed chamber," and thereupon immediately begin to prepare herself for marriage at 16 while she is still beautiful."

Ming-era architecture helps us understand the level of solitude women lived in. The window that Du talks of is not how modern people imagine it.

"We need to seek more evidence of what kind of 'window' is in the bedchamber," Zou said, showing the audience a picture of a Ming-era house. The bedchamber window was a small opening high in the wall. From inside the room, the window slopes upwards and restricts the view to a patch of sky.

"These windows were designed to only let in sunlight, not for young women to view the outside world' Professor Zou expounded.

These restricted views stopped women visually experiencing the outside world. The implication is that even looking upon a man passing by might awaken improper feelings.

Freedom of movement was also restricted. Zou showed the audience a picture of a staircase leading to a lady's room. The thin stairway was designed to allow someone to take out the bottom steps, taking away the girls freedom to leave the room.

In ancient China, women had their feet bound at birth. This practice led to malformed feet and a lifetime of pain. With such a disability, a young lady might be able to ascend the staircase unaided even if the bottom steps were removed, but to descend would have been a difficult task without help.

Zou further explains that women of the time were expected by society to live to an unimaginable standard of perfection, and those who lived up to expectations gained concrete and symbolic rewards in the form of "Chastity Arches" -- a large archway that celebrates a woman's chastity.

These arches were erected for women who stayed loyal to their dead husbands and never remarried or showed sexual desire.

One instance of a "Chastity Arch" was built as recently as two hundred years ago, and the story surrounding this arch highlights the expectations of women.

Two sons built an archway for their mother who had stayed chaste for the decades after their father's death. When they put in the final stone, they found that it would not fit, and during the struggle the hoist broke.

The sons took this as a sign that their mother had not been chaste. They questioned her and, thinking back over her life, she confessed that she had once seen a hen and cockerel "copulating."

"The message this legend passes on," Zou said, "praises a woman's chastity yet actually denounces natural female psychological and physiological desires… and this goes so far to say that a random glance of domesticated fowl in the midst of mating also deserves a punishment from heaven.

"The fantastic tale of Du Liniang expresses the true living conditions of women in the late Ming dynasty. Tang Xianzu's "The Peony Pavilion" provides a magical way for those passionate women, hopelessly confined in their quarters, to release their love and desires."

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)