By Lin Wusun

After retirement from their official posts, Chinese diplomats used to keep a low profile. Some continued to serve in nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Most just faded away. However, this is no longer the case. Quite a number now serve at NGOs, teach at universities and/or appear on TV interviews. Still others write memoirs. Qian Qichen, former state counselor and foreign minister, created publishing history when he authored a popular book called Case Histories in Diplomacy, expounding the principles and practice of Chinese diplomacy.

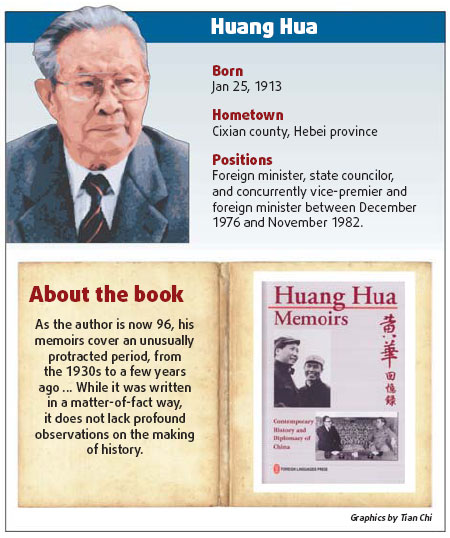

And now we have the benefit of reading the memoirs of Huang Hua, veteran revolutionary, senior statesman and diplomat-ambassador, foreign minister, vice-premier, and vice-chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. It is unique in that it provides us with tales about the source and 70-year development of modern Chinese diplomacy, based on the author's own experience and backed by materials from the Foreign Ministry's files.

As the author is now 96, his memoirs cover an unusually protracted period, from the 1930s to a few years ago. Besides, having served as ambassador in different parts of the world, often taking part in significant international conferences and other types of negotiations, and finally as China's foreign minister, Huang Hua dealt with China's relations with all types of countries, especially major ones. While it was written in a matter-of-fact way, it does not lack profound observations on the making of history.

But let's start from the book's beginning in the 1930s, when Huang Hua was studying at school and university. This was the period when an impoverished China faced the danger of being subjugated by Japanese imperialist invaders. The harsh circumstances compelled Huang Hua and his fellow young intellectuals to seek ways to save the country and to join the progressive student movement then arising in North China. The severity of the national crisis gave rise to the popular saying, "Though North China is extensive in area, it has no place for a desk where we can study." At the missionary-run Yenching University, Huang Hua was a diligent student supported by scholarship, yet he soon got involved in the salvation movement and became a student leader organizing protest demonstrations against the authorities' non-resistance policy.

The dedication and courage of the participants in the face of harsh police suppression was vividly described so that almost 80 years later we can still capture the students' idealistic fervor. Huang Hua's experience in prison, where the faithful continued their study and exchange of views through a secret hand-written publication he edited, showed him and his comrades to be persistent fighters prepared for ever-harsher challenges in the future. There have been many write-ups of this 1935 December 9th Movement, but Huang Hua's account lends a direct source rich and reliable in details. In modern China, there were more than one intellectual movement which had significant impact on the course of the nation's history, the 1935 one and the earlier May 4th Movement of 1919 being the most significant.