Monopoly no more

- By Mei Xinyu

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail Beijing Review, January 25, 2013

E-mail Beijing Review, January 25, 2013

|

|

[By Jiao Haiyang/China.org.cn] |

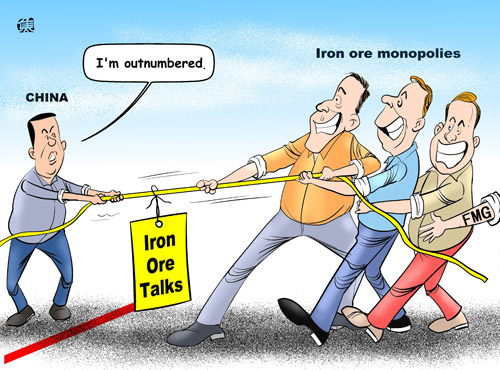

According to Barnett, a successful alliance of the two mining giants needs the approval and support of the Australian Foreign Investment Review Board, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, the Western Australia state government and parliament. Internationally it needed at least the approval of the European Union (EU) and the U.S. Department of Justice. But he did not mention that China and other big Asian steel-producing nations have a say in the case.

In fact, China, Japan and South Korea are among the world's biggest steel producers and iron ore importers and are more qualified than the United States and the EU to exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction over this case, because the possible alliance would impose a greater influence on the three Asian countries. Particularly, 70 percent of the 270 million tons of iron ore output by BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto in that year were exported to China. As the iron ore giants' largest customer, China's authority to examine and approve the case should be greater than that of the United States and the EU.

Fair environment

To emphasize China's extraterritorial jurisdiction when it comes to international anti-monopoly law does not mean China's business environment will deteriorate.

In the LCD price-manipulation case, the companies involved were fined 353 million yuan ($56.3 million). Although it is the severest penalty imposed by the Chinese Government for price fixing, but it is much lower than the penalties imposed by other countries in the same case. The United States ordered a fine of $1.22 billion, the EU fined 648 million euros ($864.73 million) and South Korea fined the LCD panel producers for 194 billion South Korean won ($183.49 million).

Although China pledges to punish any violation of the law, the purpose of China's anti-monopoly law is to establish a normal market order but not bring about the demise of any company.

Since 2010, the Chinese Government has made flat panel screens a strategic emerging industry. By the end of 2011, the LCD panel production capacity on the Chinese mainland had accounted for 20 percent of the world's total. For years, producers from countries and regions such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan had conquered over 90 percent of the global market share, with Samsung, LG, AU Optronics, Chimei and Sharp ranking as the top five LCD panel producers, accounting for 80 percent of the world's output and sales.

Punishment by the United States, the EU, South Korea and China on these long-standing giants will benefit domestic producers on the Chinese mainland. But if the aim was simply to erode the competition of overseas rivals and support the development of domestic companies, the Chinese Government should have imposed much bigger fines on these LCD panel producers.

In the face of global economic competition, growing operation costs in China has been an irreversible trend. China has been unable to maintain an advantage of low production costs, forcing China to enhance international competitiveness. A predictable legal environment is one of the components of such an environment, and China's policy makers and implementers are believed to fully understand this.

The astronomical fines by the United States and the EU in anti-monopoly cases are often based on the global sales of the involved companies, plundering the wealth of other countries, especially developing countries and regions. Anti-monopoly laws in developed countries are more advanced than in the developing world, putting the latter in an unfavorable position to exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction.

Most of the international cartel cases that have been punished are present in both developed countries and developing countries, but in developing countries with weak competition laws, monopolies by Western multinationals are particularly serious. In other words, international monopoly enterprises are plundering developing countries.

But in the anti-monopoly practice, developed countries have been investigating transnational monopolies and collecting fines for years. According to WTO figures, in the 1990s, a total of 39 hardcore cartel cases were launched in the world, involving 31 countries, including eight developing countries. However, most of these cases were investigated and fined by the United States and the EU. Except for Brazil, no other developing country had any anti-monopoly act in place, although they were seriously affected.

Developed countries, however, were calculating their fines based on global sales and seized funds that should belong to developing countries to aid their development, thereby further intensifying global income disparity.

The author is an op-ed contributor to Beijing Review and a researcher with the Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)