'Abenomics' may not cure Japan

- By Xu Changwen

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China Daily, April 3, 2013

E-mail China Daily, April 3, 2013

The Japanese economy has not recovered from its persistent deflation problem and the shocks it has suffered in the past years. After being the world's second largest economy for 42 years, it slipped to third in 2010, yielding the place to China. Even politically, Japan cannot be said to be stable. It has had five prime ministers between September 2007 when Shinzo Abe resigned as prime minister and December 2012 when he assumed office for the second time.

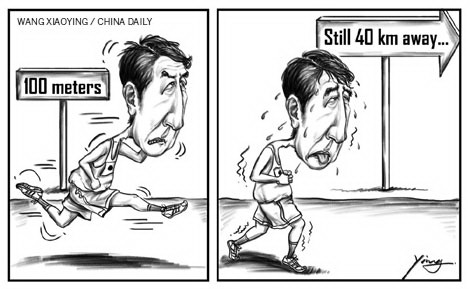

Abe may have returned to power with a landslide victory of the Liberal Democratic Party in the general election, but he has to take aggressive measures to end deflation and revive the economy to be seen as a successful prime minister.

Shortly after taking office, he introduced what many refer to as "Abenomics", a series of ambitious plans to end deflation which include aggressive monetary easing, setting a new 2 percent inflation target and a proactive fiscal policy with a generous spending of about $1.14 trillion in 15 months. Also, he has promised to unveil the details of his economic growth strategy in June.

Japan's long-term deflation is the result of stagnation of private consumption, which can be attributed to little or no increase in people's salaries. During deflation, companies neither increase their investments nor recruit new employees, let alone increasing wages. They prefer to put their money in banks to avoid risks.

To shake off deflation, the Abe government should take measures to boost private consumption which, in turn, will bolster GDP growth. Abe recently met with senior managers from major economic sectors, as well as CEOs of some large enterprises, and urged them to raise workers' pay. He even said companies that increased employees' salaries would get incentives, including some corporate tax exemptions.

Still many enterprises find it difficult to raise salaries because a depreciated yen can only theoretically add to their revenues but contribute little to their real growth. Some major companies, such as Sony and Panasonic, have been incurring losses for several years now and were even forced to sell their office buildings in places like Japan and the United States.

Thus "Abenomics" has little possibility of leading Japan out of deflation and toward real recovery in the short term. The Tokyo Stock Exchange seemed to hold out some hope in February. But it was the persistent policy of devaluing the yen that forced share prices to rise sharply and the Nikkei to reach 11,463 points on Feb 6, an increase of 32 percent from 8,667 points at the end of November 2012 and the highest since the 2008 finical crisis.

Theoretically, a sharp depreciation of the yen against US dollar can boost the revenues of export-oriented Japanese companies and make shareholders richer. But based on the short-term economic measurement of Japan's Cabinet Office, it is hardly possible to meet the 2 percent inflation target before 2014.

Moreover, Japan's move to devalue the yen will have serious repercussions on its major trading partners. Official data show that Japan's exports reached $801.28 billion in 2012, higher than 2011, but then its trade deficit reached a record $87.11 billion, an increase of $54.83 billion.

Japan's trade deficit has increased because of the decline in exports to its major trading partners such as China and the European Union. Japan's decision to "purchase" the Diaoyu Islands has cast a shadow on Sino-Japanese trade ties and reduced Japanese exports to China. In 2012, Japan's exports to China declined by $16.76 billion from the previous year, and its trade deficit with China rose to 51.8 percent of the total. In addition, the debt crisis in the EU has led to a decrease in imports from Japan. Last year, Japan's exports to the EU dropped by $13.67 billion from 2011.

Thus by inference, we can say that increased exports to its major trading partners like China and the EU will help Japan's economic revival.

The Japanese media have been saying that many countries reduce corporate tax in their fight against economic hardships. This is done to encourage enterprises to recruit more people in the hope of mitigating social conflicts and enhancing economic growth.

Though this is the first time that the Japanese government has offered to reduce corporate tax for companies that increase workers' salaries, it seems too hasty a decision given that the yen started depreciating just three months ago. This raises doubts over the effectiveness of "Abenomics" to sustain Japan's economy even in the long run.

Former Japanese prime ministers Nobusuke Kishi (in the 1950s) boosted economic growth by improving the pension system and Ikeda Hayato (in the 1960s) propelled the economy through his income-doubling plan, and both have left a mark in Japanese history.

Abe is trying to enter the history books by reviving Japan's economy through his plans to increase workers' salaries and seek a stable, long-term rule for the LDP. But no matter what he does, his success will depend on improving trade and diplomatic relations with China.

The author is a researcher with the Chinese Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation under the Ministry of Commerce.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)