Globalized is better than Americanized

- By Andrew Lam

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail Shanghai Daily, November 29, 2013

E-mail Shanghai Daily, November 29, 2013

A friend, well traveled and educated, recently viewed the evils of globalization in very simple terms.

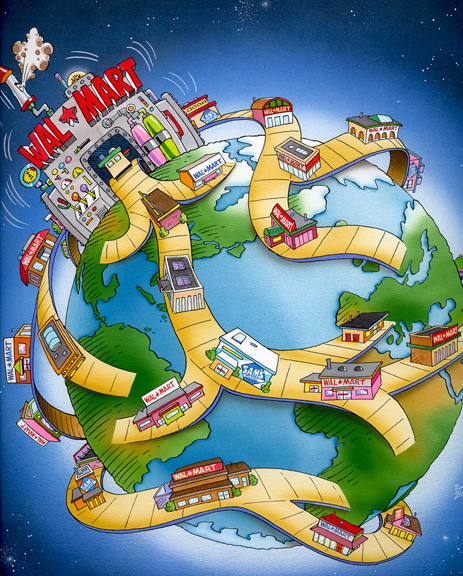

“Everyone will be drinking coffee at Starbucks, listening to Lady Gaga and shopping at mega-malls,” he said. “It’ll just be absolutely awful.” What I told him then is that globalization is not the same as Americanization, though sometimes it’s hard for Americans to make that distinction.

And that the most crucial aspect of globalization is the psychological transformation that’s affecting people everywhere.

Let me offer my own biography as an example. I grew up a patriotic South Vietnamese living in Vietnam during the war. I remember singing the national anthem, swearing my allegiance to the flag. Wide-eyed child that I was, I believed every word.

But then the war ended and I, along with my family (and eventually a couple of million other Vietnamese), betrayed our agrarian ethos and land-bound sentiments by fleeing overseas to lead a very different life.

Almost three decades later, I make a living traveling between East Asia and the United States of America as an American journalist and writer. My relatives, once all concentrated in Saigon, are scattered across three continents, speaking three and four other languages, becoming citizens of several different countries.

Once sedentary and communal and bound by a singular sense of geography, we are now bona fide cosmopolitans who, when we get online or meet in person, still marvel at the difference between our past and our highly mobile if intricately complex present.

Yesterday v today

Yesterday my inheritance was simple — the sacred rice fields and rivers that defined who I was. Today, Paris and Hanoi and New York are no longer fantasies but my larger community, places to which I feel a strong sense of connection due to familial relationships and friendships and personal ambitions.

Once great, the distances are no longer daunting but simply a matter of rescheduling.

I am hardly alone. There’s a transnational revolution taking place, one right beneath our very noses. The Chinese businessman in Silicon Valley is constantly in touch with his Shanghai mother on a cell phone while his high-tech workers build microchips and pave the information superhighway for the rest of the world.

The Mexican migrant worker moves his family back and forth, one country to the other, treating the borders as if they were mere nuisances, and the blond teenager in Idaho is making friends with the Japanese girl in Osaka in a chatroom, their friendship easily forged as if time and space and cultural barriers have been breached by their lilting modems and the blinking satellites above.

The differences between my friend’s view and my propositions are essentially the differences between a Disney animation and a Michael Ondaatje novel, say, “The English Patient.”

Disney borrows world narratives (“Mulan” and “The Little Mermaid”) for backdrops, but it rewrites all complicated stories toward a singular outcome: happily ever after.

It disembowels complexity, dismisses tragedy, forces differences into a blender and regurgitates formulaic platitudes. Thus, somewhere along the way, globalization is somehow equated to how America changes the world.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)