Feasible fowl

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China Daily, December 5, 2012

E-mail China Daily, December 5, 2012

|

|

|

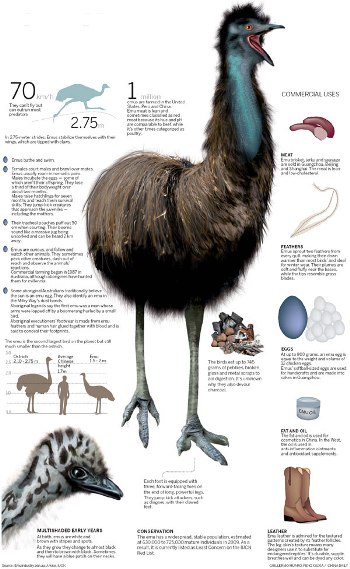

A Japanese NGO is piloting a project to replace sheep with emus in Inner Mongolia's grasslands. It could reduce overgrazing and enable ethnic Mongolian herders to earn more. |

"Even if the emus escaped, they'd have little chance to increase in the wild in Alxa because they are small in number and people are quick to capture them," OISCA Japan International Cooperation Division's Counselor Fumio Kitsuki explains.

"Apparently, emus can't survive in the wild in Alxa. Actually, many of them that escaped were captured. The others returned to the breeder on their own.

"In the unlikely event of emus having increased by several thousand, it could be considered a festive event that the birds that became extinct hundreds of thousands of years ago have now returned to Eurasia."

Several extinct ratites (large flightless birds) roamed the area millions of years ago, including Struthio wimani, S. mengi, Zhongyuanus xichuanensis and Struthio linxiaensis. The Asian ostrich is believed to have died out just after the most recent ice age and arrival of humans in China, around 10,000 years ago.

Prehistoric Chinese pottery and rock carvings depict ostriches, which some suggest inspired the concept of the phoenix.

Today, Wu cares for Inner Mongolia's reintroduced ratites year-round at OISCA's research institute in Alxa - a lonely compound in the desert outside downtown.

"It's not a bad way to live," he says.

Wulanbatu'er is the only other local to raise emus so far.

The NGO selected the 55-year-old to bring up three of the birds to test the project's viability because he already raises about 600 chickens. These fowl bring in about 20,000 yuan a year for his family of seven.

"I had wondered if these animals are suitable to raise here," he says.

"They are. They're disease-resistant, which makes them better than chickens."

Wulanbatu'er lost about 130 chickens to illness this year.

He can sell his hens for about 40 yuan a kg - less than half the price emu meat fetches.

"I hope to raise more emus," he says. "It's a good deal."

Wulanbatu'er raised sheep until his prairie turned into desert about two decades ago.

"I don't have any grass to feed the sheep," he says.

"So, I turned to chickens. I can buy food for them. Raising poultry is much better, anyway. It's better for the environment. And I don't have to spend all day outside herding them in the freezing wind, especially in winter."

Wulanbatu'er says his family used to grow fruits. It's hard to imagine today that his mash of sand dunes was once lush. He says he lives in a different place than he grew up but never moved out of his house - an earthen dwelling without plumbing, powered by a solar panel.

Alxa's average per-capita income is about 3,000 yuan a year but is much lower among the 60,000 yurt-dwelling Mongolian nomads, who rove throughout the grasslands and deserts. Their earnings have been evaporating, too, as desertification broils the terrain's flora.

Wulanbatu'er believes there are many reasons the Tengali has swallowed his land.

"It's not just overgrazing," he says.

"It's industrialization, pollution and climate change - and probably other causes I don't even know."

But he has hope for the future, he says.

"Raising emus could turn this desert back into the grassland it was most of my life," Wulanbatu'er says.

"Herding sheep is more profitable than raising chickens. But chickens are better for the environment. Emus offer both advantages. They can help us rejuvenate the grasslands and make us more prosperous than ever."

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)